Viewing a transformation that still affects all of us—through the prism of a single year

-

October 2006

Volume57Issue5

It has been called the “burned-over decade,” a “dream and a nightmare,” the “definitive end of the Dark Ages, and the beginning of a more hopeful and democratic period” in American history. It’s been celebrated in movies like

To many on the left, it is a bygone age of social consciousness and freedom. The writer William Braden observed that it ushered in a “new American identity—a collective identity that will be … more emotional, more intuitive, more exuberant—and, just possibly, better than the old one.”

To conservatives it was a time when a vast, invidious cultural revolution corroded America’s basic values. The columnist George Will scorned it as an era of “intellectual rubbish,” “sandbox radicalism,” and “almost-unrelieved excess.” Even the liberal intellectual Daniel Bell believed it gave rise to a “world of immediate gratification and exhibitionist display.”

It was the 1960s, and it didn’t begin when you think it did. It began on January 1, 1964.

Consider for a moment the state of affairs in the weeks just following John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963. Billboard magazine’s Top 20 list was dominated by “Sugar Shack,” sung by Jimmy Gilmore & the Fireballs; “He’s So Fine,” by the Chiffons; Little Peggy March’s “I Will Follow Him”; and “My Boyfriend’s Back,” by the Angels. No Bob Dylan. No Beatles. No Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, or The Who. Just innocuous pop of the sort purveyed by Bobby Vinton and “The Singing Nun.” The calendar might have marked the end of the 1950s, but the music was still there.

Leaf through the pages of the 1963 student yearbook at Columbus High School, in Columbus, Indiana, and you’ll find rows of confident young Americans—the boys all short-haired and clean-shaven, identically attired in tweed jackets and thin dark ties (with the exception of one Thomas Whittington, who donned a black bow tie); the girls, modest in their long-sleeved, high-necked blouses, wearing their hair either up or cropped just above the neck. No sideburns, no long hair, no open collars, no flower power. Just a bunch of future IBM managers and their future housewives.

What Time magazine famously observed of those coming of age in the 1950s—“the most startling thing about the younger generation is its silence”—still largely applied to high school students and collegians in the early 1960s. “We’re a cautious generation,” a student at Vassar had informed Newsweek just a few years earlier. “We aren’t buying any ideas we’re not sure of.” Another student said: “You want to be popular, so, naturally, you don’t express any screwball ideas. To be popular, you have to conform.”

These were the days when Tom Matthews, a high school senior in California, could run for class president on the stirring platform “Vote for Tom—He’s a Real Good Guy.” “That’s the way we were,” Matthews later remarked. “… Around my high school, guys were still padding the halls in saddle shoes and humming ‘Sh-boom.’ A nice girl was a virgin who didn’t smoke cigarettes. Ideology? No one even heard of it. There were no issues. We were suspended closer to the Age of Sinatra than the Age of Aquarius.”

If the kids were still loitering in the 50s, so were their parents. In early 1964, people had tremendous faith in their elected officials, their elders, the police, and the Army. 76 percent of respondents to the University of Michigan’s American National Election Study that year that they could trust the federal government to do what was right “most of the time” or “just about always.” By the close of the decade, barely half of all Americans had faith in their public institutions. But those days of popular cynicism and skepticism still lay in the future.

So things stood in the weeks after John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Few people then could have imagined how quickly their lives—and the country—would change. For 1964 was the year of The Beatles, Mississippi Freedom Summer, and the Gulf of Tonkin, three phenomena that changed the country forever. Americans woke up on January 1 still living in the quiet 1950s. They went to bed on December 31 in the stormy 1960s.

At 1:20 p.m. on February 7, 1964, four mop-topped (as the inescapable epithet went) performers from Liverpool, England, got off a Pan Am flight at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York, where they were greeted by more than 3000 screaming fans.

“There were girls, girls, girls and more girls,” wrote a local newspaper reporter. “Whistling girls. Screaming girls. Singing girls. They had beatles we love you and welcome signs.” As the plane touched down in front of the international-arrivals terminal, fans broke into cries of “We want The Beatles.” An airport official remarked, shaking his head,“We’ve never seen anything like this here before. Never. Not even for kings and queens.”

After clearing customs, The Beatles—John Lennon and Ringo Starr, age 23; and Paul McCartney and George Harrison, age 21—held a press conference (“bedlam,” The New York Times remarked), at which their already-celebrated wit and irreverence were on full display. “We have a message,” McCartney announced, prompting 200 reporters and photographers, representing a full range of American and international publications, to fall instantly silent. “Our message is: Buy more Beatles records!”

McCartney hardly needed to press the point. The Beatles had already sold six million albums in Britain and America and commanded fees upward of $10,000 for a week’s performance schedule. They were fast on their way to becoming the most popular music act in history. So far-reaching was their popularity that, when the band members arrived in Washington, D.C., by sleeping car several days later, 2000 frantic devotees all but broke through the glass barricade the police had put up at Union Station. “You can’t throw her out,” one of the teenagers protested as a policeman attempted to eject her overzealous friend from the adjacent concourse. “She’s president ofTthe Beatles fan club!” Another police officer probably summed up the bewildered opinion of adult America when he noted, simply, “The world has gone mad.”

To young people like Danielle Landau, a 15-year-old Brooklyn native, The Beatles embodied a sharp and welcome break with the culture she had grown up in. “They’re different,” she said, “they’re just so different. I mean, all that hair. American singers are soooo clean-cut.”

There was nothing new, of course, about rock music. Ten years earlier, when the Crew Cuts, an all-white band, and the Chords, an all-black band, recorded competing versions of “Sh-Boom,” and when Bill Haley and His Comets released “Rock Around the Clock,” music critics had noted the arrival of a new and dynamic form of popular song that fused country and Western traditions with rhythm and blues traditions. When a popular New York disc jockey began opening his show with the tag line “Hello, everybody, yours truly, Alan Freed, the old king of the rock and rollers, all ready for another big night of rockin’ and rollin’; let ’er go!” the emergent genre found its name. Then and since, few Americans realized that rock ’n’ roll was a black slang term for sexual intercourse.

The most popular rock act in the 1950s, of course, was Elvis Presley, whose electrified, hard, rhythmic versions of black and white gospel music caught fire with America’s young. Presley’s record producer, Sam Phillips, had previously attempted to crack national audiences with recordings by black performers like B. B. King, but the rigid color line proved an insurmountable barrier to success. “If I could find a white man with a Negro sound,” Phillips reportedly told friends, “I could make a billion dollars.” In Elvis Presley, he had his man.

Yet, for all its popularity in the 1950s, rock never fully displaced softer variations on the popular song. Well into the early 1960s, tunes like “Tammy,” by Debbie Reynolds, and “Mack the Knife,” by Bobby Darin, commanded top slots on Billboard ’s ranking tables, along with music by such clean-cut crooners as Pat Boone, Perry Como, and Frank Sinatra.

After 1964, everything changed. Within two years of their arrival in America, the Beatles dominated the pop charts, along with their harder-edged competitors the Rolling Stones, Motown groups like the Supremes, and folk-rock groups like The Byrds.

Ironically, the sound that The Beatles helped pioneer claimed deep roots in the United States. When John Lennon and Paul McCartney played their first public performance together on October 18, 1957 at the Conservative Club in Norris Green, Liverpool, the Quarry Men, as the band was then called, was self-consciously mimicking so-called race music, imported from the States, as well as white rock impresarios like Elvis, who were interpreting (or, depending on one’s perspective, appropriating) black music for white audiences.

The Quarry Men (soon renamed Johnny and the Moondogs, then The Silver Beetles, and finally The Beatles) were also part of the skiffle craze that swept England in the 1950s. A contemporary English writer described the hybrid skiffle genre as “light-hearted folk-music with a jazz slant and a very definite beat—normally sung to a background of guitars, bass and drums only.” Its most successful practitioner in postwar Britain was Lonnie Donegan, a native Glaswegian who was raised in East London, where he learned to play the banjo and the guitar. His upbeat versions of blacks’ and whites’ traditional songs like “Rock Island Line” and “Cumberland Gap” were tremendously successful among Britain’s increasingly affluent teenagers, who snatched up three million copies of just one Lonnie Donegan single in the space of six months.

The Beatles were one of dozens of Liverpool-area skiffle-rock acts trying to make it big in the early 60s. The Searchers, The Merseybeats, The Beatcombers, The Four Jays, The Undertakers, Faron’s Flamingos, Kingsize Taylor and the Dominos, Gerry and the Pacemakers … but for fortune, any of them could have swept the American market in 1964. By force of luck, talent, sweat, and brutal, hard-nosed business sense (with very little ceremony, the band fired its longtime drummer, Pete Best, on the eve of its first recording session in 1962), it was The Beatles that wrote the soundtrack for the decade.

Having refracted the sound waves of early American rock through the acoustics machine that was British popular culture, The Beatles arrived in America at exactly the right moment to sell a “new” sound to American youth—just as the first batch of baby boomers was packing off to college and as the last batch was emerging from the womb.

Courtesy of the population bubble that produced 76 million children between 1946 and 1964, a higher birthrate than in any era before or since, young Americans not only represented a larger portion of the general population, but also formed a more unified, self-conscious entity. Whereas fewer than half of all Americans completed high school in 1946, by 1970, over three-quarters did, and just under half of all 18-year-olds were receiving some form of higher education.

Even as early as the 1920s, when school enrollments began to climb, the sociologists Helen and Robert Lynd wrote in their famous study Middletown, that “high school, with its athletic clubs, sororities and fraternities, dances and parties, and ‘extracurricular activities,’ is a fairly complete social cosmos in itself… . Today, the school is becoming not a place to which children go from their homes for a few hours daily, but a place from which they go home to eat and sleep.”

This observation held even more strongly in the 1960s. As teenagers spent more time with one another and less time with adults, and as they enjoyed increasing amounts of spending money, thanks to part-time jobs and allowances, they naturally sought a culture of their own. The Beatles delivered it—even if at the time very few fans understood how wholly American the roots of the new British pop-rock were.

Moreover, because The Beatles were so manifestly exotic and foreign, they could safely cross the musical color line without raising too many hackles. They were the right people, at the right time, in the right place.

In the end, it hardly mattered how their music developed. The Beatles unleashed a pent-up force in America that created fertile ground for artistic experimentation. Ultimately, the four Britons helped American youths seize the cultural institutions of their country. Who could have anticipated that these same American youths would soon demand control of its political institutions as well?

In later years, Carolyn Goodman would remember her middle son, Andy, as gentle and soft-spoken—“sotto voce,” a peacemaker among his brothers, who were “always at each other’s throats,” and among his friends. “When he would come running to me,” she wrote, “it usually was to complain not that a brother was picking on him, but that someone was unjustly picking on someone else. I still hear his little voice piping, ‘It isn’t fair .’”

One of Andy’s high school friends from New York recalled him as a deeply “serious” individual with an abiding interest in “political and moral issues.” Though he enrolled in Queens College in 1962, intending to devote himself to theater and the arts, Andy soon discovered the civil rights movement.

A year earlier, college authorities had banned the Black Muslim leader Malcolm X and the black Communist Benjamin Davis from speaking on campus. Following the example of the Southern civil rights movement, whose revolt against Jim Crow was shaking the nation to its core, the Queens College student body went out on strike. In a demonstration of will that presaged the Berkeley Free Speech Movement of 1964, more than 70 percent of the student body boycotted classes and attended a rally in the center quad to register their disapproval of president Harold Stoke’s summary crackdown on political expression.

By the time Andy Goodman arrived on campus, the Queens student body was consumed by politics. His parents noticed that “a change began to come over Andy. His excitement over the theater began to fade, and an interest in the real world began to grow.” He switched his major to anthropology and wrote a research paper on the Black Muslims, arguing that “while it is somewhat of a fantasy to believe that all white men are devils, it is true that the white man (and, by this, I mean Christian civilization in general) has proved himself to be the most depraved devil imaginable in his attitudes toward the Negro race.”

He likened the ascendance of black radicals to “the rise in temperature that follows upon the sickness” and maintained that “the source and cause of the need for reaction can be attributed to white contempt and neglect. The historical contempt that the white race held for the Negroes as created a group of rootless degraded people. The current neglect of the problem can only irritate the deplorable state of affairs.”

Borrowing from Martin Luther King, Franz Fanon, and Malcolm X, Andy wrote that “a people must have dignity and identity. If they can’t do it peacefully, they will do it defensively.” He grew increasingly troubled by the failure of the federal government to enforce the constitutional liberties to which black Americans were entitled, and began transferring his fascination with the argot of theater to the world of politics. “The words are illusion if things aren’t so in reality,” he complained to his parents, who approved wholeheartedly of the connections he drew between dramatic and social illusion. Like so many young people coming of age in 1964, Andy Goodman was beginning to sense a crisis of authenticity.

By April 1964, when Aaron Henry, the state president of the Mississippi branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, paid a visit to Queens College, Andy was already hooked. “The thundering silence of the good people is disturbing,” Henry warned. Jim Crow was “a family problem, and there are no outsiders.” The semiofficial purpose of his visit was to recruit students to participate in Mississippi Freedom Summer, a bold initiative sponsored jointly by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Congress of Racial Equality, and the NAACP. The idea was to bring upward of 1000 white college and graduate students to Mississippi, where they would help experienced civil rights activists register voters and staff alternative summer schools—Freedom Schools—for black youngsters. At the end of the summer, they would return home to help raise consciousness there about the black struggle.

Andy Goodman scarcely needed convincing. For several years, Ralph Engelman, his best friend in high school, had been talking about his own travels through the South. Ralph, who was studying at Earlham College, a small Quaker school in Indiana that had a strong tradition of intellectual inquiry and social activism, managed to be on the periphery of the great freedom struggles with an uncanny precision that kept Andy in awe.

In late 1961, Ralph and three of his college friends had hitchhiked to Nashville, Tennessee, where a year before, the student sit-in movement had grown to maturity. Obliging passersby offered the boys a lift but warned them against stirring up any trouble in Tennessee. Ralph played it safe and lied, telling people that they were just headed down South to attend a big fraternity party. Upon arriving in Nashville, the group quickly found John Lewis, the national chairman of SNCC. The next day, they trained in a church basement with a new group of volunteers and participated in several lunch-counter sit-ins throughout the city.

Two years later, stirred by the wrenching television coverage from Birmingham, where Eugene “Bull” Connor’s men turned high-pressure fire hoses on children as young as 10, Ralph hitchhiked down to Alabama and found Reverend James Bevel, Martin Luther King’s chief lieutenant on the ground and a veteran of the Nashville sit-in campaign. For two weeks, Ralph worked as a volunteer organizer for Bevel, helping coordinate movement activities out of the basement of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

After years of listening to Ralph’s stories of the Southern movement—of the gospel singing and fiery speeches at Fred Shuttlesworth’s church, of seeing Martin Luther King at the Gaston Hotel, of watching local citizens attack news reporters with clubs and spray-paint their camera lenses—Andy Goodman wanted to be part of the action.

A week after Aaron Henry’s visit to Queens College, Andy interviewed for a spot with the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project. “I’ve talked with him here,” the SNCC recruiter Jim Monsonis reported to the project headquarters in Jackson, Mississippi, “and feel he ought to be accepted. He is a white student with some political sophistication and knowledge about the state, and is particularly interested in voter-registration work and the political campaigns.”

Later that month, while Andy joined 200 other Queens College students on a picket line outside the New York City pavilion at the World’s Fair in Queens in an attempt to draw attention to white complicity in upholding Jim Crow, the organizers approved his application. Still shy of his 21st birthday, Andy would need his parents’ permission before the Freedom Summer staff would agree to include him in the Mississippi voter-registration drive. He waited for an opportune time to broach the subject with them.

Carolyn Goodman would never forget that conversation. “He might just as well have said, ‘I want to go off to war.’” She was tongue-tied when Andy announced that he wanted to join the black freedom struggle in Mississippi. It was left to Bob Goodman to ask, simply, why?

“Because this is the most important thing going on in the country,” Andy replied. “If someone says he cares about people, how can he not be concerned about this?”

In later years, Bob and Carolyn relived that moment over and over. They didn’t want to say yes, but they couldn’t say no. “Suddenly,” Carolyn said with a sigh, “here was Andy ready to commit himself in a most real and perhaps terrifying way to a belief which all our lives we had cultivated in our children. Was I to say, ‘Andy, this is none of your business?’

“If my son now felt that a fight for human dignity in Mississippi was his business—was the business of his generation—was I to say, ‘No, no. I lied when I said a person must act on his beliefs. I didn’t mean it.’” Andy’s parents were “frightened beyond words.” But they signed the permission slips and sent him on his way.

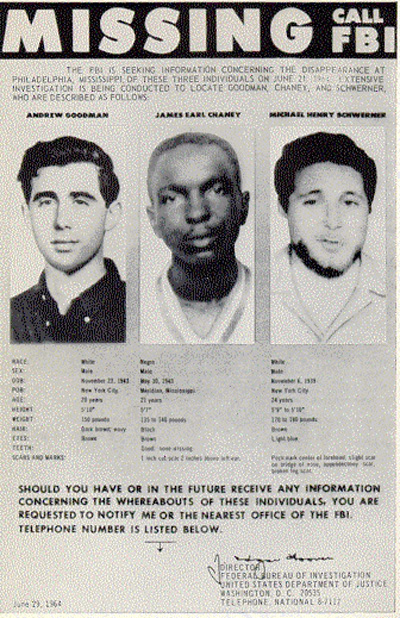

Weeks later, after attending a brief training session in Oxford, Ohio, with hundreds of other summer volunteers, Andy set out for Mississippi, where he had been assigned to work with two experienced field secretaries in Meridian and Neshoba Counties. Within 24 hours he was dead.

In 1964, Philadelphia, Mississippi—the Neshoba County seat—was a quiet town of 5500 residents, most of them white and of modest circumstances, living their lives in tidy ranch-style houses adorned with New Orleans grillwork and plantation-style porticoes, and the rest poor and black, inhabiting small, drafty “nigger shacks,” often without indoor plumbing or electricity. Apart from its neat white-steepled church, a handful of steel stacks that sent up gray smoke from the town’s three sawmills, and a high water tower bearing the town’s name, Philadelphia was an unremarkable place, tucked away behind a thick forest of fragrant second-growth pine and set high on one of the sweeping red-clay hills that slope along the easternmost sliver of the state.

By the early 1960s, the town was losing population, and fast. Even in its heyday, Philadelphia hadn’t been much to look at. The “business district” was a handful of brick buildings, two or three stories tall, stretching out along eight city blocks. The courthouse was the center of what civic life there was. People were said to be kind and generous. It was the kind of place where you’d stop to stretch your legs, fill up the gas tank, grab a bite to eat—and leave.

There, on the evening of June 21, 1964, Cecil Price, the deputy sheriff of Neshoba County, delivered three civil rights workers—Andrew Goodman, aged 20; James Chaney, aged 21; and Michael Schwerner, aged 24—into the hands of a mob. Goodman had been in Mississippi for only one day. He and Schwerner, a field secretary for the Congress of Racial Equality who also hailed from New York and had been in Mississippi for several months, were each murdered by a single bullet to the chest. Chaney, a black staff member with CORE’s Meridian office and a born-and-bred Mississippian, was beaten senseless, then killed with three gunshots to the head and chest.

The execution party placed the bodies in the trunk of a nondescript sedan and buried them at a remote site where contractors were in the process of building an earthen dam.

Testimony would later reveal that, as he aimed a gun at Schwerner’s chest, Alton Wayne Roberts, a member of the posse, asked, “Are you that nigger lover?” Schwerner replied, “Sir, I know just how you feel.” Roberts shot him dead.

44 days later, the bodies were discovered. The public announcement of the deaths created a groundswell of sympathy for the civil rights movement that followed on the heels of a remarkable legislative achievement—the passage and enactment in early July of a new law that President Lyndon Johnson said would go “further to invest the rights of man with the protection of law than any legislation in this century.”

Sweeping in its reach, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 barred segregation in places of public accommodation, including hotels, movie theaters, parks, restaurants, and stores; prohibited labor unions and employers from discriminating in hiring or promotions on the grounds of race or gender; created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to monitor compliance with the employment regulations; and empowered the government in Washington to suspend federal funds for states that still segregated their schools and other civic institutions.

The bill had been a long time in coming. John Kennedy pressed for it in the months before to his assassination, but grassroots civil rights organizations had been agitating for at least a decade to see passage of its employment and public accommodations sections. When Lyndon Johnson signed the law into effect on the evening of July 2, in an East Room ceremony at the White House, it was far from clear that the South would accept enforcement of its provisions. Just that afternoon, Representative Howard Smith of Virginia had denounced the act as “this monstrous instrument of oppression upon all of the American people.”

Speaking to a national television audience, LBJ announced that “we have now come to a time of testing. We must not fail.”

A year or two earlier, it wouldn’t have been unthinkable for the Deep South to resist compliance with the new law. But, in the aftermath of the bloody civil rights campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963, and now in the wake of the murders of the three civil rights workers in Neshoba County, the country was in no mood to brook further dissent from Dixie.

Weeks after Johnson signed the new civil rights bill into law, newspapers across America covered a press conference that the Goodman and Schwerner families held in New York City. There, in a voice cracking with emotion, Andy Goodman’s father told reporters that “our grief, though personal, belongs to the nation. The values our son expressed in his simple action of going to Mississippi are still the bonds that bind this nation together—its Constitution, its laws, its Bill of Rights.

“Throughout our history, countless Americans have died in the continuing struggle for equality. We shall continue to work for this goal and we fervently hope that Americans so engaged will be aided and protected in this noble mission.” At the close of his remarks, Goodman wept in the arms of a family friend.

The triple murder in Mississippi had a profound impact on public opinion. On the eve of the 1963 March on Washington at which Martin Luther King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, Americans disapproved of the planned demonstration by a margin of 60 percent to 23 percent, an indication of how skeptically most people still regarded the black freedom struggle. By September 1964, 59 percent of respondents to a Gallup poll voiced approval of the new civil rights law, compared with 29 percent who opposed it.

Jim Crow had spent its last credit with the American public, and the smartest segregationists realized it. “As long as it’s there,” Senator Richard Russell of Georgia said of the Civil Rights Act, “it must be obeyed,” a sentiment echoed by the Louisiana senator Allen Ellender, who reluctantly admitted that “the laws enacted by Congress must be respected.”

Though some firebrands like Mississippi’s governor, Paul Johnson, urged citizens and businesses not to comply with the law, by late 1964, most Southern towns and institutions had dismantled the rigid segregation apparatus that had defined local race relations since the 1880s. “Colored” and “White” signs came down, signaling the final disappearance of American apartheid.

The road ahead wasn’t a smooth one. Battles remained over voting rights, open housing, and economic opportunity—battles that would take the civil rights movement to new and unexpected places, like the urban North, and which would usher in a more confrontational style of activism and protest. After Freedom Summer, civil rights became a national issue, and it defined the political debate for the rest of the decade.

On August 2, as FBI agents in Neshoba County waded through Mississippi swampland amid a 106-degree heat wave in search of the bodies of the three missing civil rights workers, 12 time zones away, off the northernmost coast of North Vietnam, the U.S. destroyer Maddox was patrolling the waters around a cluster of small islands in the Gulf of Tonkin near North Vietnam. The ship’s commander, Captain John Herrick, was engaged in the DeSoto Patrol, a top-secret intelligence operation, surveying the Hanoi regime’s shore-defense system. As Herrick steered through the choppy Pacific waters that afternoon, three North Vietnamese PT boats emerged from behind Hon Me Island and swiftly closed with the destroyer. Though technically entitled to the privileges of maritime neutrality, the Maddox retreated to open waters; the PT boats followed in close pursuit, then launched torpedoes. Herrick sent a distress signal that led a nearby Navy carrier, the Ticonderoga, to scramble its fighter jets, which swiftly sank one PT boat and disabled the remaining two.

Thousands of miles away, in Washington, D.C., aides awakened President Johnson to inform him of the attack. The President’s response was swift and unequivocal. Johnson ordered the Maddox to resume its operations—for good measure, he teamed her with a second destroyer—and warned Hanoi that any further incitements would invite a military response. LBJ was acting at least in part out of perceived political necessity. His opponent in the fall election was Senator Barry Goldwater, a conservative Arizona Republican and vehement anti-Communist who had electrified the GOP National Convention earlier that summer when he declared that “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice” and “moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” Johnson was determined not to be outhawked. He scarcely needed his Texas friend Robert Anderson to remind him that “you’re gonna be running against a man who’s a wild man.”

The next day, on August 3, under direct orders from the Pentagon, Herrick once again steered his ship toward the North Vietnamese coastline, but, when his radar suggested a torpedo attack, he quickly veered toward Hainan, a nearby Chinese island. In the hours that followed, the Maddox appeared to be under attack. Later that day, Herrick re-evaluated the afternoon’s events and informed his superiors that “many reported contacts and torpedoes fired appear doubtful. Freak weather effects on radar and overeager sonar men may have accounted for many reports. No actual visual sightings by Maddox .” Despite this follow-up report, Johnson pressed ahead. On Wednesday, August 5, just as FBI agents were uncovering Michael Schwerner’s shirtless corpse in the Olen Burrage Dam, the president ordered a five-hour-long battery of air strikes on North Vietnamese military targets.

Two days later, Johnson demanded and won congressional passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which authorized the Commander in Chief to employ “all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression” in Southeast Asia. The measure passed unanimously in the House of Representatives and by a vote of 88 to 2 in the Senate. The only dissenters were the Alaska Democrat Ernest Gruening and the Oregon Democrat Wayne Morse.

Few observers could have imagined how quickly LBJ would avail himself of these unprecedented and sweeping powers. Though he promised a national television audience on the evening of August 4 that he would “seek no wider war,” between the incidents of August 1964 and late 1965, the number of servicemen fighting in Vietnam rose from 17,000 to 184,000. By late 1966 the figure had climbed to 450,000, and by early 1968 more than 500,000 Americans were serving in the steadily escalating conflict.

Historians and political analysts have long debated the extent of Lyndon Johnson’s responsibility for the tragedy that was the Vietnam War. Some have convincingly argued that his predecessor, John Kennedy, had grown circumspect about the direct engagement of ground forces after the Bay of Pigs fiasco of 1961, and that he would never have committed combat troops to Vietnam. By this rendering, LBJ was too personally and intellectually insecure to reject the misguided advice of that group of advisers whom David Halberstam would later dub the “best and the brightest,” the same Ivy-educated technocrats who designed and botched the war. Others, however, have argued with equal force that Johnson inherited a situation he could scarcely have maneuvered past.

As early as the Truman administration, policymakers had agreed that Southeast Asia must not be allowed to “fall into the hands of the Communists like a ripe plum.” Truman’s successor, Dwight Eisenhower, declined in 1954 to dispatch U.S. troops to bail out the beleaguered French (though America financed 80 percent of the French war), who were forced by the nationalist Vietminh army to withdraw from Southeast Asia after a calamitous defeat at Dien Bien Phu. But Ike did not see Vietnam as unimportant. On the contrary, he said the French had “a row of dominoes set up. You knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is a certainty - that it will go over very quickly. So, you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences.” Rather, Eisenhower had a low opinion of the French military capabilities and thought that it would require an enormous commitment of resources—and a highly destructive land war—to weed out the nationalist forces.

Instead, Vietnam was partitioned, with an eye toward reunifying the country in 1956. America began propping up the government in South Vietnam, while North Vietnam, under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, turned gradually to the Soviets for military and economic assistance. With American prodding, South Vietnam resisted the scheduled 1956 elections, realizing that it was almost a certainty that Ho Chi Minh would become president of a unified Vietnam. For its part, Washington continued to treat the government in Saigon as a client state, hoping for a peaceful stabilization of affairs. The assassination of South Vietnam’s president, Ngo Dinh Diem, in November 1963 left John Kennedy at a crossroads. He could commit more military advisers and economic assistance to a regime that was increasingly ineffectual and corrupt, and which seemed incapable of meeting the challenge posed by the Hanoi-backed National Liberation Front, or he could remove the American presence from Vietnam. His assassination three weeks later meant that his thoughts on the question will forever remain a matter of speculation.

On the eve of Johnson’s ascension to power, Vietnam remained divided, and Americans remained committed to the rhetoric of the Cold War, which viewed any retreat as a dangerous crack in the national armor. In September 1963, when the Harris Survey organization asked Americans if it was worth going to war with China—a nuclear power—in order to prevent South Vietnam from falling to the Communist bloc, 29 percent of respondents favored war, 34 percent favored a withdrawal, and 37 percent were uncertain. The same survey revealed that 72 percent of Americans supported the government’s general policy in Vietnam.

Even in the aftermath of the Gulf of Tonkin incident, as Johnson began increasing troop levels in Southeast Asia, 45 percent of Americans wanted to stay the course in Vietnam; 36 percent wanted to “step up the war by carrying the fight to North Vietnam, for example, through more air strikes against communist territory”; while only 19 percent supported pulling out. In short, by a large margin, Americans demanded victory of their leaders. They fundamentally agreed with their martyred President Kennedy that America should “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

Lyndon Johnson, then, was acting with the full faith and support of his electorate. In later years, he lamented: “I knew from the start that I was bound to be crucified either way I moved. If I left the woman I really loved—the Great Society—in order to get involved in that bitch of a war on the other side of the world, then I would lose everything at home. All my programs… . But if I left that war and let the Communists take over South Vietnam, then I would be seen as a coward and my nation would be seen as an appeaser, and we would both find it impossible to accomplish anything for anybody anywhere on the entire globe.”

The decisions made in early August 1964 would reap terrible consequences: LBJ’s civil rights and anti-poverty agendas derailed; families and communities were sundered; 58,000 Americans and as many as three million Vietnamese died, along with hundreds of thousands of Laotians and Cambodians; and the nation was no longer confident in its ability to meet the challenges of what Henry Luce had once called the American Century.

Along with civil rights, the war would dominate the front pages of American newspapers and the evening news broadcasts for a decade to come.

Speaking to Congress on January 4, 1965, President Johnson evaluated the year that had just ended. “This, then, is the state of the Union,” he proclaimed. “Free and restless, growing and full of hope. So it was in the beginning. So it shall always be, while God is willing, and we are strong enough to keep the faith.”

The 1960s had begun.

Joshua Zeitz is the author of