At the Gettysburg reunion fifty years after the battle, it was no longer blue and gray. Now it was all gray.

-

June/July 1978

Volume29Issue4

The most dramatic and tragic moment of the American Civil War was the climactic point of Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 3, 1863. This doomed assault brought the Southern Confederacy to what looked like the verge of triumph, broke up in dust and fire, and put the armies on the road that led inevitably to the surrender field at Appomattox. Nothing in all the war has been written about so exhaustively.

For a slightly different angle, begin with the familiar setting: Union infantry and guns massed on Cemetery Ridge, boiling smoke clouds brimming the shallow valley in front, shadowy movement all along the milewide stretch of woodland on Seminary Ridge a mile to the west — then the smoke drifts away as the bombardment stops, and out on the open ridge step Pickett’s fifteen thousand, lining up with military formality, sunlight glinting from rifle barrels and bayonets as the men dress ranks for the advance. And finally the charge begins, disciplined thousands crossing the open field to meet the disciplined defenders in blue, breaking out at last in the wild, nerve-tingling Rebel yell as they come within close range, and the men in blue level their rifles to shoot them down.…

Before they fire, skip fifty years to July of 1913 to see the conclusion.

![[Union and Confederate veterans shaking hands at reunion to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Civil%20War%20Veterans%20at%20Gettysburg.jpg)

In 1913 the government arranged for a joint North-South commemoration of the battle of Gettysburg. Not all the wounds left by the Civil War had healed entirely — civil wars cut deep — but at least the country had recognized itself as one nation forever more, and 1913 seemed like a good time to make a public demonstration of the fact. So various keepers of documents were called on to supply names and addresses of surviving veterans of the battle, and such veterans as were able and willing to attend were invited to return to Gettysburg at no cost to themselves and see what battlefield and antagonists looked like half a century later.

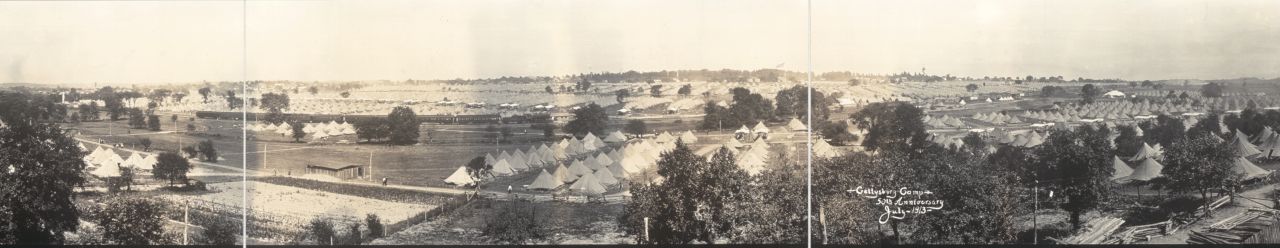

A big tent city was laid out on the field, complete with hospital tents, doctors, and ambulances — after all, when you hold an outdoor convention of seventy-year-olds with a lot of walking around and a powerful emotional strain, you are apt to have a few casualties — and there were bakeries, kitchens, dining tents, and all manner of conveniences these men had lacked on their first visit to the place. Several thousand veterans showed up.

So did the tourists, who came in swarms, along with the people who make a living by going where tourists are. Among these latter were photographers — what tourist could fail to buy on the spot pictures of the old-timers, especially when he himself could get into the scene? — and to our good fortune one of these cameramen hired as an assistant an eighteen-year-old college man-on-vacation named Philip Myers. Not long ago Mr. Myers wrote down his recollections of the great event.

“We went to Gettysburg late in June,” he wrote, “but by the time we arrived the town was overflowing with thousands of visitors. We considered ourselves fortunate to bivouac in the haymow of a barn on the edge of town.” This photographer took Devil’s Den for his base of operations, and a day of scrambling up and down the ponderous rocks in this area left the young collegian very tired at nightfall. But somehow it was impossible to go to bed; every night the two men sat in the door of the haymow and looked out at the tented city. Mr. Myers recalled it:

“One by one the lights in the tents were extinguished, the singing ceased and an eerie calm embraced the encampment. A brilliant moon created soft radiance as, at eleven o’clock, a bugler at nearby headquarters broke the silence with the hauntingly melancholy notes of Taps. When the last plaintive notes of that somber call had faded, he was followed by another trumpeter farther off, then by another still more remote, and another, until it was impossible to tell if the notes we heard were real or imaginary.”

Between the tourists and the veterans themselves the photographer and his helper put in a full day every day (and were the rest of the summer clearing up the backlog of developing and printing). There were two shots in particular that Mr. Myers remembered.

One was a cigar-smoking Yankee veteran who held his hand to his cheek while drawing on his stogie. Mr. Myers protested that this spoiled the photo by hiding most of his face, and the veteran explained. He himself had been on Little Round Top during the battle, but here he was in Devil’s Den, because “I want to see where that so-and-so who shot me must’ve been standin’.…” He went on:

“I’m a-fightin’ and a-yellin’ at the top of my lungs, when his bullet come along an’ catches me right in my mouth. But what with yellin’ my mouth is wide open, so it misses my teeth an’ comes outta my cheek. An’ when it heals, it don’t close up tight. There is still a little hole there. If I don’t plug it with my finger I don’t get no draft on my smoke.” He took a deep puff and with lips tightly pursed blew smoke out through his cheek.

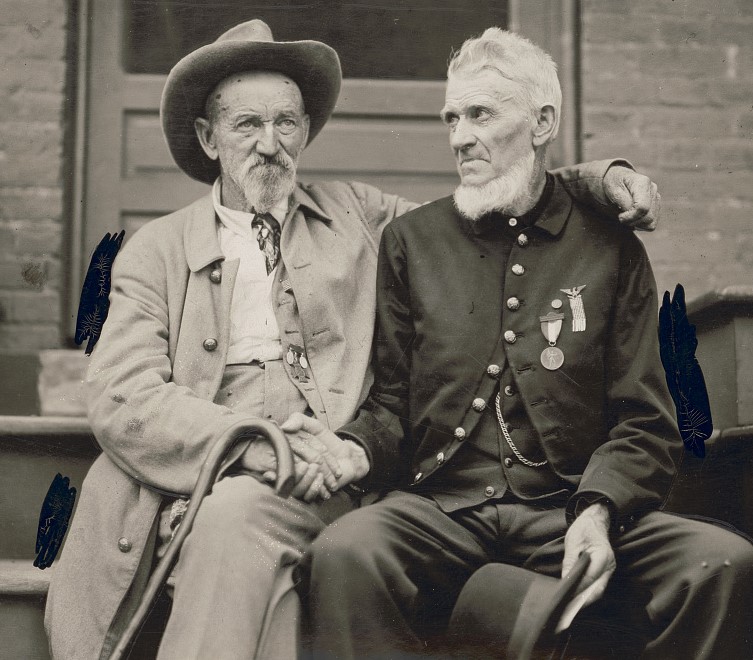

Mr. Myers’ other memorable picture came once when he was making the favorite shot—a Yank and a Reb standing with arms intertwined. (“I must have made a thousand exposures of it.”) A tall, stately Confederate with a great shock of wintry hair called two Union veterans to his side, placed his arms on their shoulders, and demanded a photograph. The photographer remarked that the big campaign hats shaded their faces and suggested that they take off their hats. The men complied, and the Reb ran his fingers through his hair.

“Son,” he said to the camerman with a courtly bow, “fifty years ago it was the blue and gray. Now it’s all gray.”

Unfortunately, almost all the pictures this photographer made have disappeared in the years since the reunion. (The pictures we reproduce here were taken by his competitors.) Although relations between former foes were harmonious, serious arguments did develop here and there.

“One of the more serious ones took place in a restaurant near the Jennie Wade House,” wrote Mr. Myers. “After violent words had been exchanged across the table, a Reb and a Yank had at each other, not with bayonets this time, but with forks. Unscathed in the melee of 1863, one of them — and I never learned whether North or South — was almost fatally wounded in 1913 with table hardware!”

Incidentally, Mr. Myers had feared that a good many of the old veterans would die during the encampment. The Army Quartermaster Corps apparently felt the same way, for it was reported to have stockpiled a considerable number of coffins. Fortunately, hardly any of these were needed. Old soldiers apparently are a tough breed.

…and we come at last to the afternoon of July 3, and the great re-enactment of Pickett’s charge, with thousands on thousands of spectators gathered all about, Union veterans on Cemetery Ridge, Southern veterans on Seminary Ridge to the west. Out of the woods came the Southerners, just as before well, in some ways just as before. They came out more slowly this time, and Mr. Myers saw a dramatic difference: “We could see, not rifles and bayonets, but canes and crutches. We soon could distinguish the more agile ones aiding those less able to maintain their places in the ranks.”

Nearer they came, until finally they raised that frightening falsetto scream. “As the Rebel yell broke out after a half century of silence, a moan, a gigantic sigh, a gasp of unbelief, rose from the onlookers.”

So “Pickett’s men” came on, getting close at last, throwing that defiant yell up at the stone wall and the clump of trees and the ghosts of the past.

“It was then,” wrote Mr. Myers, “that the Yankees, unable to restrain themselves longer, burst from behind the stone wall, and flung themselves upon their former enemies. The emotion of the moment was so contagious that there was scarcely a dry eye in the huge throng. Now they fell upon each other — not in mortal combat, but re-united in brotherly love and affection.”

The Civil War was over.