Recently discovered documents shine a new light on the President’s biggest decision

-

April/May 2003

Volume54Issue2

What did President Harry S. Truman and his senior advisers believe an invasion of Japan would cost in American dead? In recent years this has been a matter of heated historical controversy, with Truman’s critics maintaining that the huge casualty estimates he later cited were a “postwar creation” designed to justify his use of nuclear weapons against a beaten nation already on the verge of suing for peace. The real reasons, they maintain, range from a desire to intimidate the Russians to sheer bloodlust.

See also: The Biggest Decision: Why We Had To Drop The Atomic Bomb, by Robert James Maddox

One historian wrote in The New York Times, “No scholar of the war has ever found archival evidence to substantiate claims that Truman expected anything close to a million casualties, or even that such large numbers were conceivable.” Another skeptic insisted on the total absence of “any high-level supporting archival documents from the Truman administration in the months before Hiroshima that, in unalloyed form, provides even an explicit estimate of 500,000 casualties, let alone a million or more.”

A series of documents recently discovered at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library & Museum in Independence, Missouri, and described by this author in an article in the March 2003 Pacific Historical Review, tells a different story.

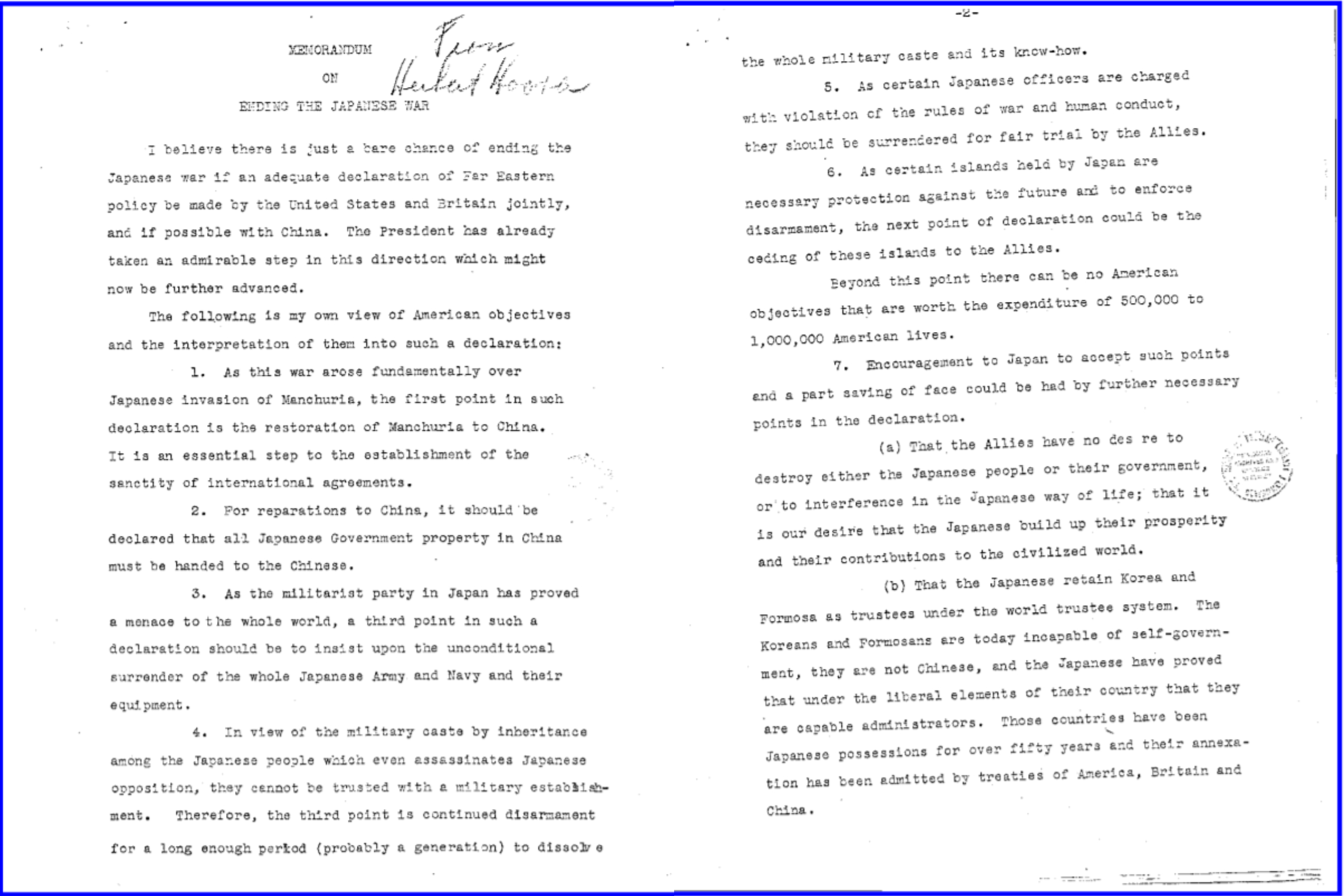

In the midst of the bloody fighting on Okinawa, which began in April 1945, President Truman received a warning that the invasion could cost as many as 500,000 to 1,000,000 American lives. The document containing this estimate, “Memorandum on Ending the Japanese War,” was one of a series of papers written by former President Herbert Hoover at Truman’s request in May 1945.

The Hoover memorandum is well known to students of the era, but they have generally assumed that Truman solicited it purely as a courtesy to Hoover and Secretary of War Henry Stimson, who had been Hoover’s Secretary of State. As it turns out, however, Truman had a much higher opinion of Hoover than do today’s historians.

“What we now know,” says Robert Ferrell, the editor of Truman’s private papers, “is that Truman seized upon this memo and sent memoranda to his senior advisers asking for written judgments from each.” Moreover, adds Ferrell, this discovery “not merely shows that Truman knew about such a high casualty figure” far in advance of the decision to use atom bombs but that he “was exercised about the half-million figure—no doubt about that.” Yet another discovery, by the Hoover Presidential Library’s former senior archivist, Dwight Miller, indicates that the estimate likely originated during Hoover’s regular briefings by Pentagon intelligence officers.

Truman forwarded the memorandum to the director of the Office of War Mobilization and Reconversion, Fred M. Vinson, on June 4. Vinson had no quarrel with the casualty estimate when he responded three days later. He returned the original memo along with one of his own, suggesting that Hoover’s paper be shown to Stimson, Acting Secretary of State Joseph C. Grew, and former Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Truman sent copies of the memo to all three men, asking each for a written analysis of it and summoning Grew and Stimson to a meeting to discuss their analysis with him.

Grew immediately forwarded the memo to Judge Samuel L. Rosenman, a longtime adviser and speechwriter for FDR who was then serving as Truman’s special counsel. Stimson, meanwhile, passed on his copy to the Army’s deputy chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Thomas J. Handy, because he wanted to get “the reaction of the [Army] Staff to it,” and he mentioned in his diary that he “had a talk both with Handy and with Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall on the subject.”

Hull was first to respond. Although branding the memo an “appeasement proposal” because it suggested that the Japanese be offered lenient terms to entice them to a negotiating table, he did not take issue with the casualty estimate. Grew, in his reply to the memo, confirmed that the Japanese “are prepared for prolonged resistance,” adding that “prolongation of the war [will] cost a large number of human lives.”

Stimson wrote: “We shall in my opinion have to go through a more bitter finish fight than in Germany….” Truman also met with Adm. William Leahy on the matter. In addition to serving as the President’s White House chief of staff, the admiral was his personal representative on the Joint Chiefs of Staff and acted as unofficial chairman at their meetings. Leahy sent a memorandum stamped URGENT to the other JCS members, as well as to Stimson and Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, saying that the President wanted a meeting the following Monday afternoon, June 18, to discuss “the losses in dead and wounded that will result from an invasion of Japan proper,” and he stated unequivocally: “It is his intention to make his decision on the campaign with the purpose of economizing to the maximum extent possible in the loss of American lives.”

See also: Half A Million Purple Hearts, by Kathryn Moore and D.M. Giangreco

At the Monday meeting all the participants agreed that an invasion of the home islands would he extremely costly—but that it was essential for the defeat of Imperial Japan. Stimson said he “agreed with the plan proposed by the point Chiefs of Staff as being the best thing to do, but he still hoped for some fruitful accomplishment through other means.” Those other means ranged from increased political pressure brought to bear through a display of Allied unanimity at the imminent Potsdam Conference to the as-yet-untested atomic weapons that might “shock” the Japanese into surrender.

As for Truman, he said at the meeting that he “was clear on the situation now and was quite sure that the Joint Chiefs of Staff should proceed” but expressed the hope “that there was a possibility of preventing an Okinawa from one end of Japan to the other.”