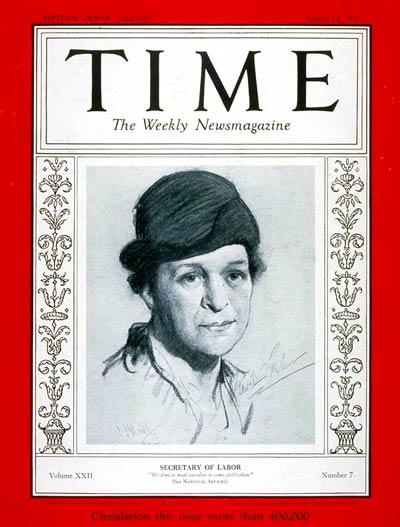

FDR's Secretary of Labor — the first female Cabinet member — also helped create the minimum wage, the 40-hour work week, and the first tough child labor laws.

-

Spring 2021

Volume66Issue3

Editor's Note: Bruce Watson is a writer, historian, and contributing editor at American Heritage. You can read more of his work on his blog, The Attic.

MANHATTAN — MARCH 1911 — The women had just sat down to tea when the screaming began. Fire was raging through a nearby sweatshop. As sirens wailed, hundreds gathered to watch. A towering building was burning, its garment workers trapped, clinging in smoke and flame to upper stories. By the time Frances Perkins left her tea and ran to the scene, young women were falling from the sky. Some were ablaze.

Frances Perkins might have been a teacher, a nurse, a professor. Born into an upper crust New England family, she wore stodgy hats and dresses that seemed, one critic noted, “designed by the Bureau of Standards.” All her life she pronounced “labor” as “lay-bah.”

But the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire set Perkins on a course to help the people who built America. People like you. If you have Social Security, if you work a 40-hour week, if you ever earned overtime or minimum wage, received unemployment insurance or workman’s comp, this prim and proper woman deserves your thanks, and not just on Labor Day. Because for Frances Perkins, every day was Labor Day.

Perkins’ turn away from teaching started when she volunteered at Hull House in Chicago. After touring the tenements with Upton SInclair, whose novel The Jungle captured urban squalor, Perkins devoted her life to reform. Yet reform required power, and what could she do in a country where women could not even vote?

— Frances Perkins

Perkins’ climb took her to the Wharton School and then Columbia where she studied social economics. Her quick mind served her well. By 1911, she chaired the New York Consumers League. In the wake of the Triangle fire, she headed the commission that studied the tragedy. She was appalled. Factory conditions at Triangle were a nightmare dreamt by Dickens. Doors were locked. Stairways clogged. Women worked 60+ hours per week. Where to begin?

Perkins spent the next two decades in New York politics. She lobbied tirelessly for child labor laws, for factory inspections, and the eight-hour day. But ironclad power, welding big business to politicians of both parties, blocked labor legislation. Whenever a law slipped through Congress, the Supreme Court struck it down. Workers must be FREE! FREE of government interference! By 1930, European Labor had a solid safety net, but American workers were free to work and work and work, free to get old and die.

Then in 1933, Perkins’ boss, New York governor Franklin Roosevelt, reached the White House. Weeks before his inauguration, FDR called Perkins into his office. Would she be willing to accept a new job — Secretary of Labor? No woman had ever held a cabinet post. And Perkins knew that FDR was lukewarm about labor. She reached in her purse and pulled out a piece of paper. On it she had written:

— 40-hour week

— minimum wage

— workers comp

— unemployment insurance

— federal ban on child labor

— Social Security

— health insurance

“Nothing like this has ever been done in the United States before,” she told FDR. “You know that, don’t you.” The congenial Roosevelt paused, then said he would back her. She thought it over a night, wept at the strain it would put on her husband and daughter, then took the job.

The press mocked “Ma Perkins,” “Frances the Perk.” In person, however, she insisted on being called “Madame Secretary.” And she ran Labor with a tight hold. Strikes during the Depression were violent class wars, but Perkins struggled to keep calm. In 1934, she convinced the Attorney General not to send the army to San Francisco to break a gritty longshoremen’s strike. “The soldiers will fire,” she said. “Somebody will get hurt. The mob will attack. There will be some regular shooting and a lot of people will drop in the streets.” Perkins convinced the AG to call FDR. The president insisted on arbitration. Two days later the men were back at work.

That summer, FDR put Madame Secretary in charge of a commission considering social security. It should not be seen as a tax, the president insisted, but “an investment.” Perkins deftly handled the commission’s egos, drafted the legislation herself, and a year later the Social Security Act was signed. FDR called it “the cornerstone of my administration,” but Frances Perkins saw it as mere “flat-footed first steps.”

Three years later came the Fair Labor Standards Act. Then minimum wage. Then overtime for 40+ hours a week and the first tough child labor laws. You’re welcome.

By the time Frances Perkins died in 1965, she had helped create that rudder of society — the middle class. Corporate America has been trying to roll back her programs ever since, but most stand rock solid. That’s because Frances Perkins knew that “the roots of social security stem from that deep well of charitableness that resides in the American people.”