She functioned as Franklin Roosvelt's de facto chief-of-staff, yet Missy LeHand's role has been misrepresented and overlooked by historians.

-

Summer 2017

Volume62Issue1

On the morning of July 2, 1932, a slender, neatly dressed young woman with dark hair already threaded in silver stepped out of a car at the grass-and-gravel airport in Albany, New York. Her name was Marguerite Alice LeHand, but everyone knew her as Missy. Air travel was a new experience for the thirty-five-year-old woman, and though she had taken many other journeys with her boss, New York governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the stakes had never been higher than for this trip. They were flying to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, where Roosevelt had been nominated for president of the United States the night before.

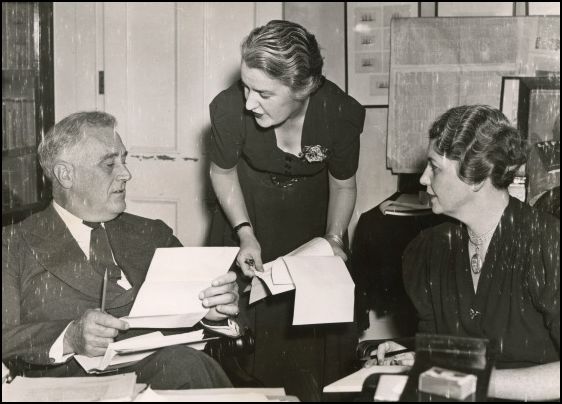

He needed Missy to help him put the finishing touches on his acceptance speech, and it had probably never occurred to her to decline making the trip with the boss she adored and called “F.D.” Boarding the tiny, corrugated metal plane, she settled into a seat in the first row, where a typing table had been set up, a shiny black typewriter ready to go to work under her capable hands.

From the day in January 1921 that she first came to work for FDR as his private secretary, Missy LeHand had found herself in some very unusual places. They included a creaky houseboat meandering down the Florida coast; a tumbledown cottage in Warm Springs, Georgia; and the front seat of a Ford convertible that FDR drove at reckless speeds down country roads in Dutchess County, New York. He managed the gas and brake with hand controls, as he was paralyzed below the waist. Stricken with poliomyelitis eight months after Missy entered his employ, FDR had found his secretary integral to his rehabilitation and eventual return to public life. Now, after almost four years as governor of New York, he was ready to claim the job he had dreamed of holding since he was a young Manhattan lawyer: the presidency.

Surely Missy felt some trepidation about F.D.’s decision to fly to Chicago, although she knew that, practically speaking, it was the only way he could get to the convention before the delegates left for home. But in a larger sense, the flight was symbolic: FDR was literally launching skyward in a bold and daring gesture to show the country he was ready, willing, and fully capable of running for national office, even if he had to “run” in a wheelchair.

See also in American Heritage: "FDR and His Women" by Ellen Feldman

The announcement of FDR’s planned appearance in Chicago had electrified the nation, and newsreel crews and reporters had swarmed the Albany airport. No candidate of either party had ever accepted a nomination in person, and the notion that the candidate would fly—something most Americans had never done—was almost as exotic as that of taking a rocket ship to the moon. Indeed, FDR had not flown for more than a decade, since serving the administration of Woodrow Wilson as assistant secretary of the navy during World War I, making brief sorties in open-cockpit planes in Europe.

–Paul M. Sparrow, director of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library

Even though FDR’s nomination had been a nip-and-tuck affair, the American Airways Ford Trimotor had been on standby at the Albany airfield for days, arrangements having been made prior to the convention to lease it with crew for $300. The crew included the pilot, a thirty-five-year-old World War I veteran named Ray D. Wonsey; a copilot; and a steward who would serve a full lunch in the tight confines of the cabin during the 783-mile journey.

Besides Missy and FDR, the party of ten passengers included his wife, Eleanor; two of their four sons, Elliott and John; speechwriter-advisor Samuel I. Rosenman; Missy’s close friend and assistant, Grace Tully; and two bodyguards and a male aide, who, along with Elliott, were primarily responsible for helping FDR move around without drawing undue attention to his paralysis.

Wearing a blue summer-weight double-breasted suit and holding a Panama hat, the Democratic nominee was assisted by Elliott into the plane, FDR characteristically bantering to distract the well-wishers on hand from the sight of a fifty-year-old man who could not get out of his car unaided. The plane had been retrofitted with a wooden ramp so FDR could walk on board using a cane and Elliott’s arm for support. He settled into a seat beside his pretty, blue-eyed secretary and began dictating a telegram to his elderly mother, Sara.

As the silver and blue plane roared down the runway and soared into the sky, FDR and his entourage passed around celebratory telegrams, and the steward handed out chewing gum, maps, and American Airways postcards. Eleanor knitted a baby sweater. Sam Rosenman and FDR worked on the speech, dictating a few changes for Missy to retype. The cabin, measuring a mere eighteen feet in length, soon filled with smoke as FDR puffed away on his Camels and Missy on her Lucky Strikes; both smoked two to three packs a day. However, the most hard-core practitioner of the tobacco habit in FDR’s inner circle was waiting in Chicago, where he had been stationed throughout the convention. Louis McHenry Howe, the wizened former newspaperman who had orchestrated the political career of “the Boss” since his days in the New York legislature, was steadily destroying what was left of his lungs by chain-smoking a brand called Sweet Caporals. He lit one cigarette off the butt of another, and his clothing was always dusted with ash.

The acceptance speech had been drafted by FDR, Rosenman, and Raymond Moley, a pipe-smoking college professor and charter member of a new group of advisors known as the “Brain Trust.” Both Rosenman and Moley would later claim authorship of the two words in the speech that became the brand of the Roosevelt era: New Deal. Neither attached much significance to them at the time.

Howe, in his sweltering Chicago hotel room, was writing his own version of the acceptance speech, convinced that launching his boss on the right foot rhetorically was as vital as getting him to the convention in the first place. Everyone in the Roosevelt camp knew that three years into the worst economic depression the country had ever seen, Americans needed hope above all things to pull themselves out of the mire. FDR, paralyzed by polio for more than a decade, was a man who knew a thing or two about hope.

See also in American Heritage: The Story Behind The FDR Tapes, by R.J.C. Butow

The plane landed to refuel in Buffalo, where FDR welcomed a few supporters and reporters on board while the other passengers climbed off and stretched their legs. In the air again, the steward served a lunch of cold chicken, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, salad, chocolate cake, and melting ice cream. While the steward reported that all “did full justice to the lunch,” they didn’t all keep it down. High winds rocked the plane and rattled the passengers. An account written by the son and grand-daughter of Captain Wonsey said, “White-knuckled passengers could only cling to the upholstered arms of the aluminum chairs. In the turbulence, acceptance speech sheets slid off the desk, and the typewriter came close to pitching off the table into Miss LeHand’s lap.” The Roosevelts’ youngest son, John, got airsick and spent most of the flight in the tail throwing up. There must have been moments when Missy wondered what in the world she was doing on that plane.

A woman of undistinguished background and an education that ended with high school, Missy had traveled far in the company of Franklin Roosevelt. She came into his orbit as a staff member for his vice presidential campaign in 1920, when he and Democratic nominee James M. Cox were soundly defeated by Warren G. Harding and his running mate, Calvin Coolidge. Invited by Eleanor to stay on for a few weeks in Hyde Park to help clean up correspondence, Missy got along so well with FDR that he asked her to become his private secretary. For the first eight months of 1921, she worked between his law office and an investment firm where he served as a Wall Street rainmaker. She was soon spellbound by the renowned Roosevelt charm.

Then, tragedy struck. In August 1921, while vacationing on Campobello Island off the coast of Maine, Roosevelt was struck by a severely disabling case of poliomyelitis, known at the time as infantile paralysis. For the next seven years he pursued treatments both conventional and outlandish in a quest to walk again, while Louis and Eleanor kept his political career alive. Though he built his upper body strength to compensate for his damaged legs, “walking” for Roosevelt required locked braces, a cane, and the arm of a strong man who sometimes went away from the experience with finger-shaped bruises. In fact, without an assistant, FDR could not rise from a chair by himself. Missy was his primary companion during this determined battle, first for long winter trips on the rickety houseboat Larooco, and then at the Warm Springs, Georgia, resort that FDR purchased and where he established, with Missy’s help, the country’s premier polio rehabilitation facility.

Much to Missy’s distress, in 1928 FDR was pressured into running for governor of New York by Alfred E. Smith, the Democratic nominee for president. In doing so, he effectively abandoned his quest to walk, because the time he needed each day for therapy had to be devoted instead to campaigning and, after election, governing what was at the time the country’s most populous state. Upon his election, Missy moved to Albany and Eleanor offered her a bedroom in the executive mansion. She was on call virtually around the clock, meeting and often anticipating not only the needs of the governor but also those of his busy wife.

After almost four years in Albany as an immensely popular governor, FDR was ready to run for national office. Missy, ever loyal, was his closest confidante and truest true believer—even if it meant getting on an airplane with him and flying straight into a storm.

The plane landed in Chicago at 4:30 p.m., two and a half hours behind schedule. The welcoming party included James A. Farley, FDR’s floor manager at the convention; the candidate’s oldest son, James; daughter Anna; and Louis Howe— along with a crowd estimated at 25,000. In the tumult, FDR’s hat was knocked off his head, and his pince-nez glasses were dislodged. Louis squeezed into the car with the Boss for the trip into town and quickly scanned the speech. Soon he was complaining about it and urging his own version on FDR. “Dammit, Louis,” Roosevelt exploded, “I’m the nominee!” However, he employed his renowned ability as what we would nowadays call a multitasker to scan Louis’s speech while waving to the crowds lining the road, and decided to substitute his first page for the one Rosenman and Missy had labored over on the plane.

A few hours later, gripping the lectern at Chicago Stadium, Roosevelt delivered a speech concluding with words that would be forever linked to his name: “I pledge you, I pledge myself to a new deal for the American people.”

There is no record of where Missy sat during this speech, but because she was considered “a member of the family,” it’s likely she was with Eleanor and the Roosevelt children. On Election Day in Hyde Park that November, the two women stood side by side on the steps of the town hall, their gloved fingers interlaced, as FDR’s supporters cheered. In one telling photo of the scene, Missy beamed, while Eleanor, who dreaded becoming first lady, looked downcast.

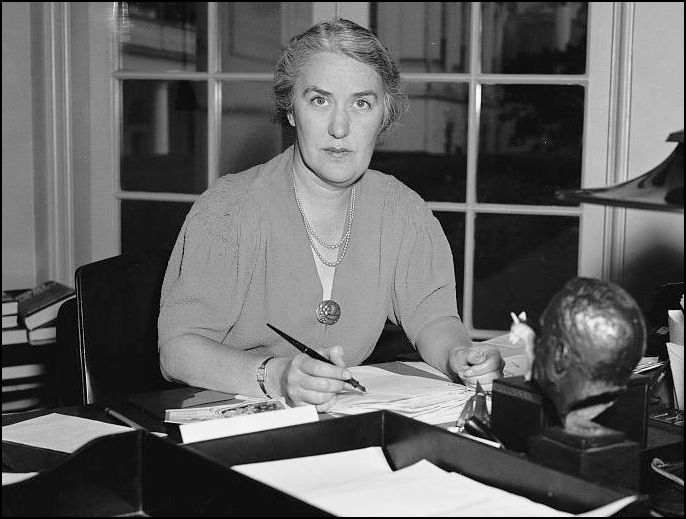

Ensconced in the West Wing right outside the Oval Office, Missy would come to wield enormous influence and power within his administration. She was the gatekeeper to the president, while also advising him on policy and appointments, speeches and actions. FDR heeded her counsel, knowing it was based on common sense, honesty, sure instincts, and unshakable loyalty to him. Sitting in the only office adjoining his, she knew every person FDR saw and the nature of the call, and she controlled the back door that bypassed his official appointments secretary and allowed visitors to slip in unseen by the press and unrecorded by the official log. She screened his mail and decided which callers could be immediately dispatched to his phone by the White House switchboard. (Among these favored callers was Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd, the woman whose love affair with FDR had almost destroyed his marriage in 1918.)

There had never been anyone like Missy in the White House before, and it was a long time before anyone like Missy followed. The only other women—besides first ladies—who have wielded as much influence over a president since Missy were Condoleezza Rice, national security advisor and secretary of state for George W. Bush, and Barack Obama’s senior advisor, Valerie Jarrett.

Rosenman, a member of FDR’s inner circle throughout his presidency and the editor of his papers, called Missy “one of the most important people of the Roosevelt era. She sought to remain out of the limelight—and succeeded. I doubt whether her real contributions to the work of the President and to her country will ever be adequately understood except by those who personally knew her and watched her in the White House.”

Rosenman’s words about Missy staying out of the limelight were not exactly accurate, for in her day Missy was famous. In 1933 Newsweek dubbed her the “President’s Super-Secretary.” She appeared on the cover of Henry Luce’s influential Time magazine in 1934 as the only female member of the White House “secretariat.” During Roosevelt’s second term she was named one of the seven best-dressed women in the capital, along with the French ambassador’s wife. The phrase “Missy knows” was repeated over and over in an admiring profile in The Saturday Evening Post in 1938. Look magazine sent a photographer to the White House for a multipage photo spread with Missy in 1940, which gave the public a glance into her apartment on the third floor and the president’s private study—well-timed publicity as Roosevelt sought an unprecedented third term.

During Missy’s time, no one had heard of “glass ceilings” hindering the advancement of women, but she broke a crucial one at the same time Eleanor became the role model for the modern first lady and Frances Perkins became the first female cabinet member. Missy was the first woman to be secretary to a president at a time when “secretary” was the top staff title in the White House. In everything but name she was FDR’s chief of staff—for the job title was not used by a president until Dwight Eisenhower adopted it to suit his sense of military structure.

FDR himself identified an even more significant role for her in his administration and life, saying often, “Missy is my conscience.” He was a Hudson Valley blue blood who was famously described as “a traitor to his class,” but Missy was a blue-collar girl from a seedy part of Boston who never let her boss forget the people he had promised to champion. Missy, wrote Washington columnist Drew Pearson, “thought about the plebes.”

When a heart condition she had developed as a child led to a disabling stroke and her departure from the White House in 1941, the gaping void in FDR’s inner circle was never filled. Partly paralyzed and robbed of the ability to speak, Missy pre-deceased her beloved F.D. by less than nine months. She disappeared from the public consciousness after her stroke, leaving only the faintest of trails.

Missy never kept a diary about the twenty-one years she spent orbiting FDR’s sun, a point of pride she mentioned in every major interview, saying she had no plans to write a memoir. Her one attempt at writing an article about her work was abandoned and never published. Her friend Robert Sherwood, a noted playwright as well as one of FDR’s best speechwriters, inscribed a copy of his Pulitzer Prize–winning play Abe Lincoln in Illinois, “For Missy LeHand, who will someday be a vitally important character in a play about the greatest President of the United States since the subject of this play.” It did not happen.

In play, movie, and television scripts, she has been marginalized as a love-starved secretary or maligned as a mistress.

Research for my book tapped a trove of letters to a man Missy loved during her time at the White House, the extensive archive kept by her family (including recently discovered home movies Missy herself shot in the 1930s), and a crucial medical document that reveals the precarious state of her health, turning almost everything previously written about Missy LeHand on its head.

What this famously discreet woman thought during the time she held a ringside seat on the most tumultuous years of the twentieth century will never be entirely known. What Missy knew, saw, heard, and did has never been pieced together—until now.

Portions of this essay appeared in Kathryn Smith's recent book, The Gatekeeper: Missy LeHand, FDR, and the Untold Story of the Partnership That Defined a Presidency.