Tears ran down the cheeks of Abraham Lincoln when he heard the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” sung in Congress in 1864 by a chaplain who had survived a Confederate prison. It would become the most famous literary production of the Civil War.

-

Summer 2019

Volume64Issue3

President Lincoln arrived late. By the time he and the First Lady took their seats in the House chamber, they had missed the evening’s convening prayer and Vice President Hannibal Hamlin’s opening remarks. The Philadelphia merchant George Stuart was well into his speech when the audience spotted the Lincolns and greeted them with “a tempest of applause” followed by a standing ovation that brought the proceedings to a temporary halt.

This was a rare public appearance for the president in 1864. He found it hard to take time away from his duties as commander in chief nearly three years into civil war. But he accepted Stuart’s telegraphed invitation to join the other dignitaries that evening in early February. The celebration in the House of Representatives marked the second anniversary of the United States Christian Commission. The order of events differed little from a worship service.

One DC newspaper described the crowd as “composed, in great part, of the religious element of the city.” They had come to reaffirm their faith in the Union war effort and renew their commitment to serve soldiers and their families. The wartime mix of state, church, and military was on full display. The audience heard from preachers and laymen active in founding and running the commission and dignitaries including the Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax of Indiana.

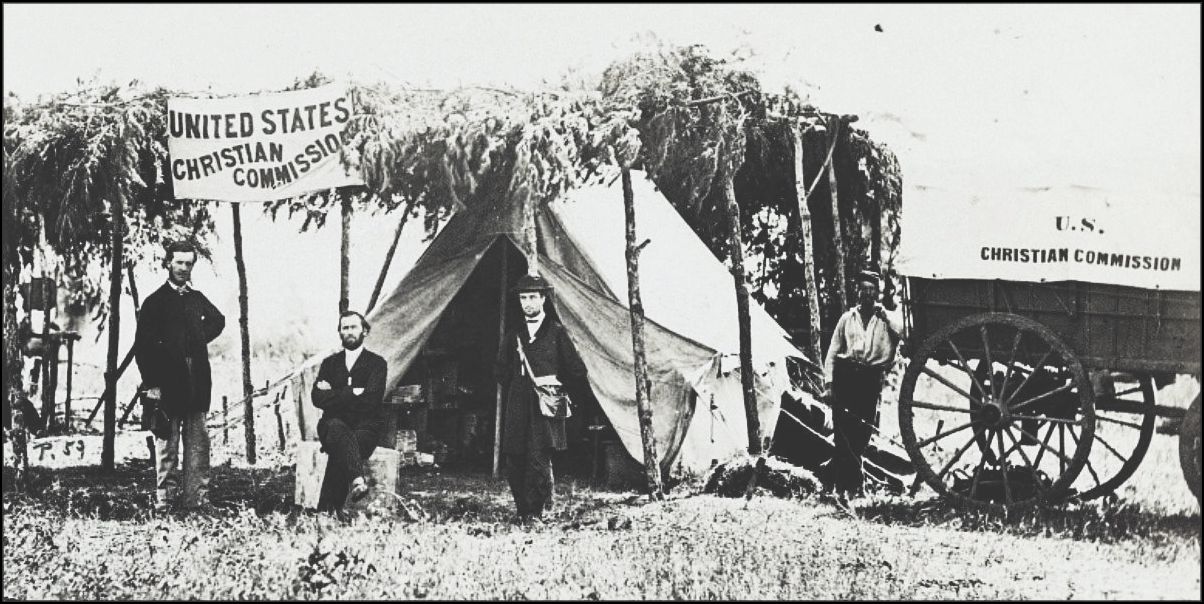

The Christian Commission had been founded on November 16, 1861, by the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) at a convention in New York City. The commission’s publicized aim was “to promote the spiritual and temporal welfare of the officers and men of the United States army and navy, in cooperation with chaplains and others.” For the sake of that calling, the commission solicited donations of goods and money, distributed Bibles, books, and tracts by the tens of thousands, promoted temperance in the encampments, and recruited volunteer workers and ministers of the gospel to care for the souls of men in uniform.

Along with the parallel United States Sanitary Commission, it tended to the sick, wounded, and dying. Its tireless chairman was the successful entrepreneur Stuart, founder of the Philadelphia YMCA. Testimonials poured in praising the work of the commission.

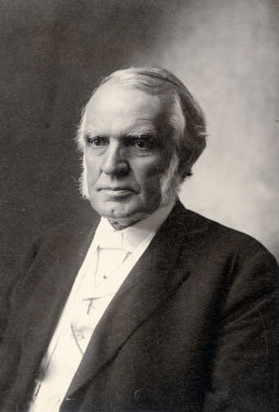

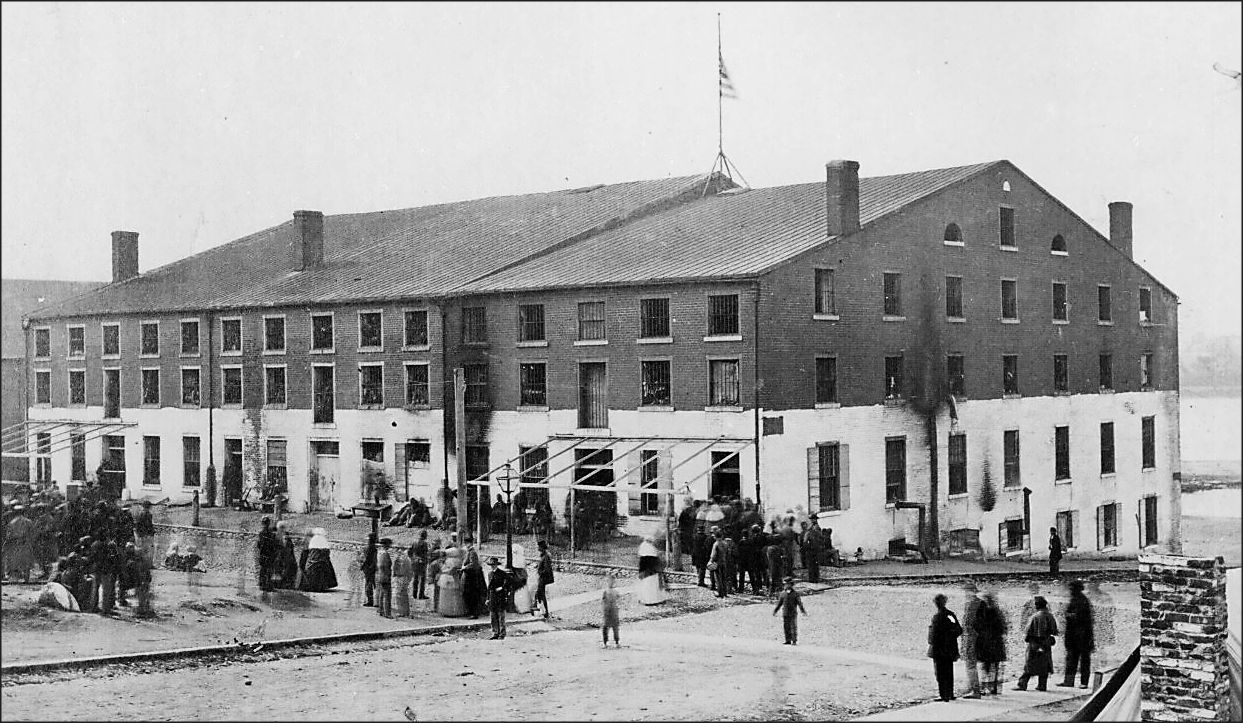

The highlight of the evening for Lincoln, and certainly for others in the House chamber, was a rendition of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” by Chaplain Charles C. McCabe, a frequent speaker and fund-raiser for the Commission. In 1862, while chaplain of the 122nd Ohio Infantry, McCabe had been captured by Confederate forces and taken to Libby Prison in Richmond. He was there on July 6, 1863, when news reached the inmates of the Union victory at Gettysburg.

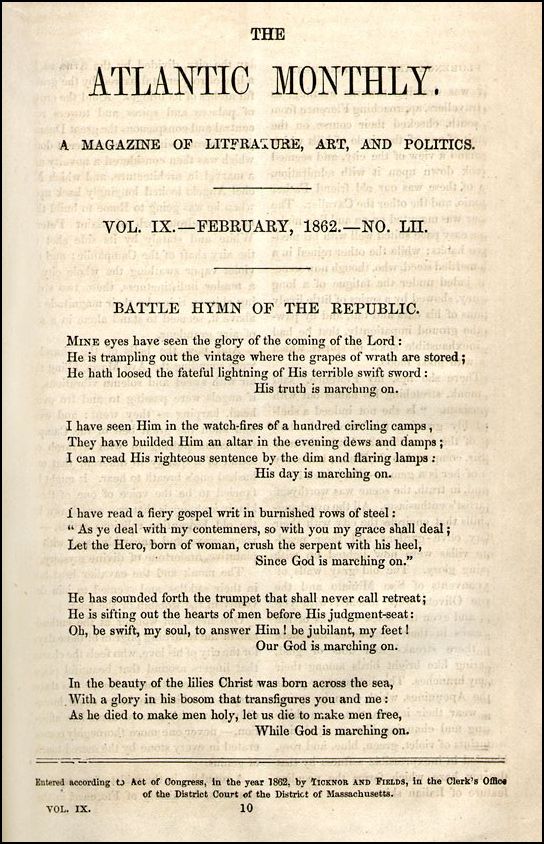

The soldiers burst into song—everything from “Yankee Doodle” to religious hymns. But then McCabe led them in singing the words of a poem he had clipped from the Atlantic Monthly and memorized. He knew Julia Ward Howe’s poem matched the cadences of “John Brown’s Body,” a favorite Union marching song, and the prisoners joined him in the chorus, singing, “Glory, glory, hallelujah!”

McCabe told this moving story of his prison experience, and then sang the “Battle Hymn” as a duet with an army colonel just released from Libby, asking the audience to join him in the chorus accompanied by a regimental brass band. According to the Sunday School Times, McCabe sang “with much sweetness and power.” Swept up by the refrain, the audience’s “enthusiasm was aroused to such a pitch, so that few scenes like it have ever been witnessed in a public gathering.”

“Applause greeted the ending of nearly every stanza,” the account continued, “and in the last, before reaching the chorus, the pent up enthusiasm could be restrained no longer, but burst forth in a torrent of exultant shouts and cheers that made the Hall ring to the roof.”

Soon, President Lincoln shouted, “Sing it again!” and Vice President Hamlin announced that McCabe would repeat his performance. Before he did so, McCabe delivered a charge to the president from a fellow Libby prisoner “in the name of the martyrs of Liberty”: “Tell the President not to back down an inch.”

Lincoln replied, “I won’t back down.”

Shouts of “Amen!” came from the crowd. The uproar and the whole evening were unlike any spectacle most had ever witnessed.

For the twenty-seven-year-old McCabe, this had been a thrilling commemoration at the Capitol. He was seated right in front of the Lincolns. He wrote to his wife before going to bed that night that during the speeches of two pastors he had seen “tears [roll] down the rugged cheeks” of the president.

The press agreed that “there were few dry eyes in the hall” as pastors told gruesome and sentimental stories of caring for the wounded after Antietam and Gettysburg.

According to McCabe’s diary, when the president saw him again at a White House reception two weeks later, “Mr. Lincoln recognized me as the man who sang the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic’ at the Capitol and was kind enough to compliment both the song and the singing. My vanity was considerably delighted. Sure, and how could I help it?”

From this point on, McCabe helped make the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” inseparable from the Union cause. At fund-raising events across the country for the duration of the war and for years afterward, the Methodist chaplain and later bishop would center Howe’s poem in a decidedly evangelical setting—closer to the childhood she had left behind than to the world of liberal religion she promoted as an adult. He sang the anthem and told the story of Libby Prison for decades.

By the time Julia Ward Howe wrote the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” the abolitionist and mother of six was already a respected author and poet whose writing had appeared in Atlantic Monthly and other journals. The daughter of a wealthy New York banker, she had grown up in a world of privilege, of books, art, and music, good manners and witty banter, all tempered by evangelical piety.

Julia’s marriage in 1843 to physician and abolitionist Samuel Gridley Howe plunged her into the intellectual, religious and reform world of Boston. Her husband counted the leading intellectuals and authors of the city among his friends, and as the furor over slavery grew he had joined in the “Secret Six” conspiracy to arm and fund John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. Howe was forced to flee to Canada for a time to avoid arrest.

After the War began, Julia’s contributions to the Atlantic and Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune became more prominent. In November 1861, seven months after the attack on Fort Sumter, she and a group of prominent Bostonians including Massachusetts Gov. John Andrew traveled to Washington to look into the progress in the war and the work of the Sanitary Commission. Julia hoped to see the encampments and battlefields that she had only imagined from a distance in Boston, and wanted to somehow contribute to the cause of emancipation as well as restoration of the Union.

The group stayed in the Willard Hotel near the White House, attended church services, and visited Congress and the White House, meeting with President Lincoln. When she heard soldiers singing “John Brown’s Body,” Julia later recalled, she “remarked to a friend that [she] had always wished to write some verses which might be sung to that tune.”

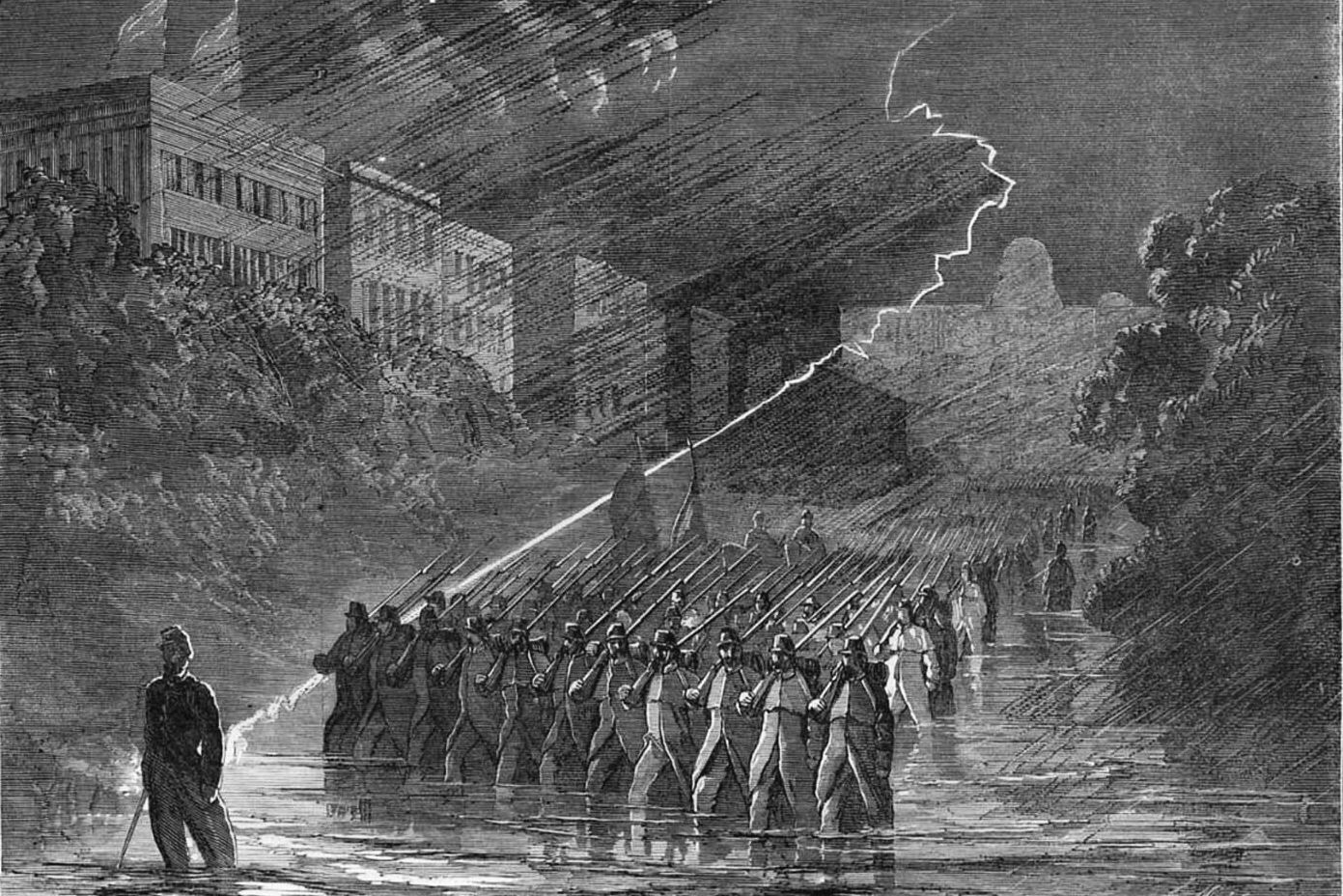

On November 18, the group obtained military passes to travel to Northern Virginia to witness a review of Gen. Irwin McDowell’s division of 10,000 troops, including soldiers from Massachusetts. The review was interrupted when messengers alerted McDowell about a nearby skirmish involving some of his pickets and Confederate cavalry, and he immediately dispatched troops to repel the attack.

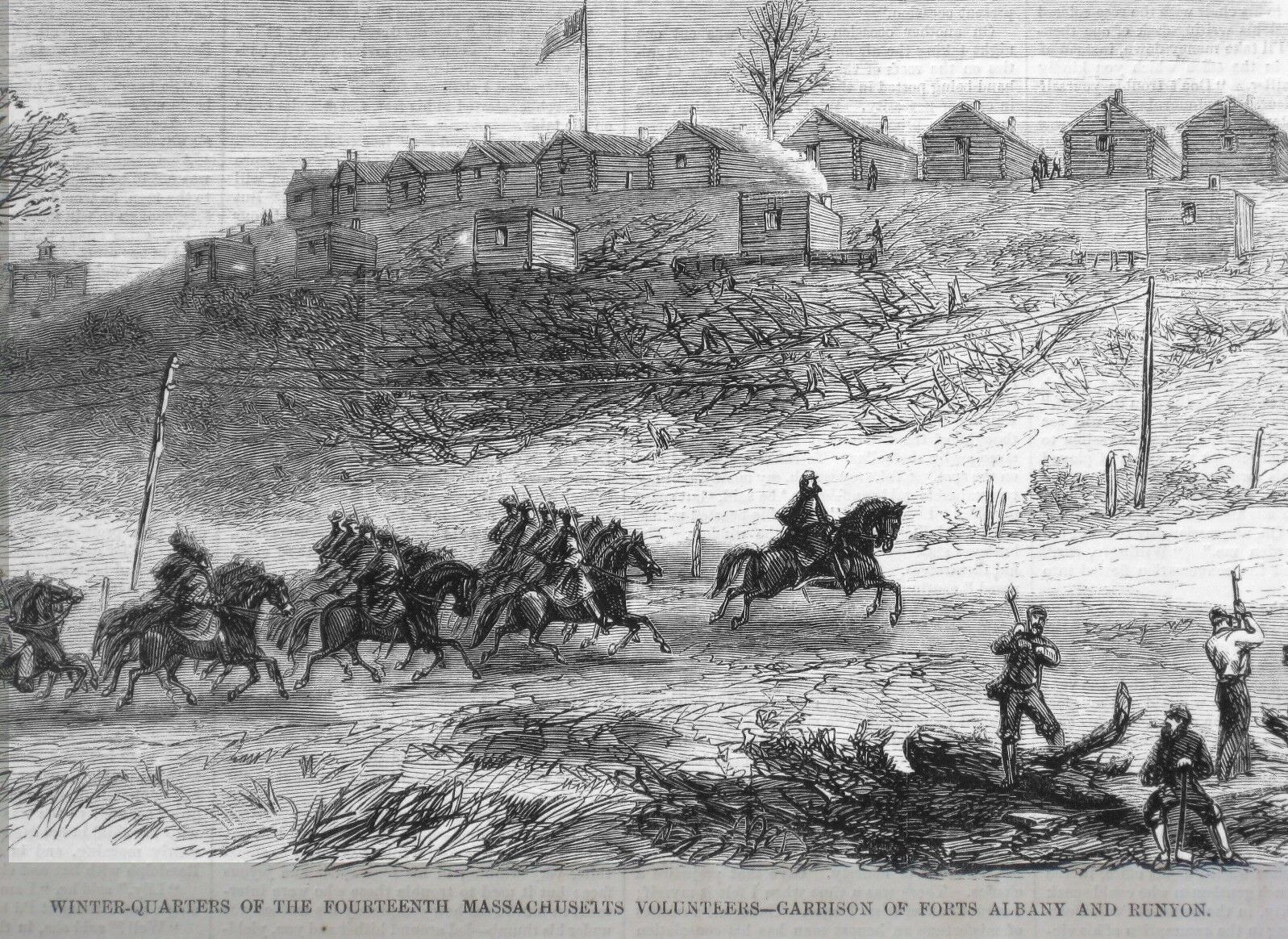

“The excitement to us was great, for we did not know, nor probably did the Generals, but that it might be the beginning of a great battle,” wrote Rev. James Clarke, a minister in the group, later. “We left our carriage and climbed on the ramparts of a fort near by, where we could see better. The firing continued in the distance for perhaps three fourths of an hour.”

Julia did not want to leave the scene and sang songs “appropriate to the hour,” Clarke later wrote. Eventually, they headed back toward Washington. “Long streams of red flames ran over the hills, and followed the courses of dried-up streams, choked with sticks and leaves. So at last, passing the heavy gates of Fort Albany and Fort Runnion [sic], we reached the Long bridge, and returned into Washington, bearers of the news of another skirmish.”

Having heard the John Brown song, having seen the encampments in the twilight and the campfires dotting the scene, and having heard bugle calls piercing the air, Julia returned to the Willard and went to bed. By her own account, she woke before dawn the next morning. She often experienced half-waking, half-sleeping dreams or visions, at times in great detail. Troubled and depressed by the state of the Union effort, she looked out over the moonlit streets of Washington from her hotel room window.

Later, a friend recalled that, “She told us that her mind was so burdened with sorrow for her country that she knew not whether she slept or not but finally a vision seemed to envelop all her faculties. . . . Slowly the vision, call it inspiration or revelation, as you will, was outside and beyond herself. It took form in prophetic words and lines of verse, till she could no longer remain quiet.”

In the dark, Julia groped around for a scrap of paper. She was in the habit of using any bit of paper, including the backs of envelopes and the reverse sides of letters, to jot down notes for lectures and essays or fragments of poetry as they came to her. To write out the poem that morning she used a piece of Sanitary Commission stationery. The surviving manuscript includes six stanzas, with only four words crossed out and replaced.

Given what Julia had seen and heard from the moment her train approached Washington five days earlier— the encampments in Maryland and Virginia, the soldiers marching and singing, the apocalyptic preaching — she had a wealth of images at her disposal, images of the “watchfires of an hundred circling camps,” the “dim and flaring lamps,” the “fiery rows of steel,” and God’s fearful yet glorious wrath — a world of sacred flags and sacred rivers, of holy cities and holy wars, of martyr heroes and atoning blood.

Through her imagination, war, nation, and faith fused into the perfect poetic expression of the North’s religious nationalism, an anthem worthy of the nation in its hour of peril.

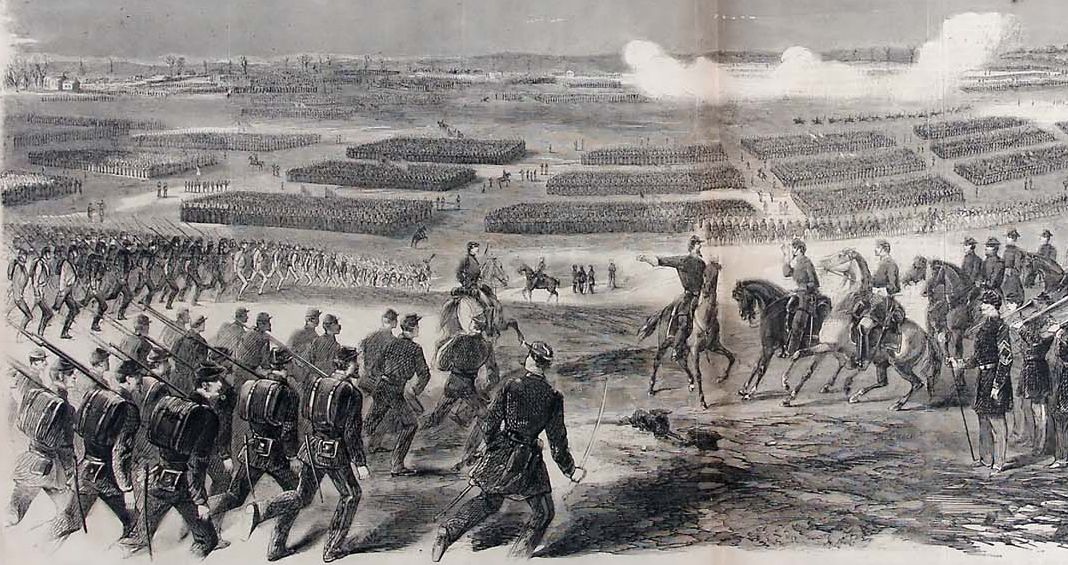

Monday's skirmish with the Confederates did not deter Julia from returning to the encampments. Wednesday promised to bring the highlight of the week. General McClellan and the Army of the Potomac staging a spectacular “grand review” for President Lincoln. As the new head of the Union army, McClellan had every reason to ensure his men put on a good show for the politicians and their guests. Julia and her party joined the throng determined to witness the grand review. As many as 20,000 spectators, including President Lincoln and his cabinet, converged on the fields between Bailey’s Crossroads and Munson’s Hill.

Military passes were not required that day. The roads became so congested that simply reaching the parade ground from the city took half the day. When Julia and her friends finally arrived, they saw thousands of infantrymen joined by cavalry regiments, military bands, artillery salutes, and McClellan and his staff on horseback reveling in it all with Lincoln and his cabinet. It was the largest military review ever staged in North America. It took three and a half hours for the regiments to pass, which the Washington Evening Star estimated totaled 75,000 men. This at last appeared to be a fighting force ready for action, irresistible in its magnitude and skill, the hope of the besieged city and fractured nation.

The next day, Julia boarded the train back to Boston, and later claimed that on the trip she read the yet unnamed poem to her minister.

The Atlantic Monthly published the poem the following February, 1862, and soldiers were soon singing it throughout the Army and ministers reading it from pulpits. The song became an embodiment of the religious nationalism that swept the country during the long, brutal war.

For years afterwards, Julia helped to popularize her “Battle Hymn” in lecture halls, pulpits, and leading periodicals for children and adults. Especially after Samuel's death in 1876, she needed to stay busy to support herself and toured the nation for decades. The “Battle Hymn” became Howe's tagline on the lyceum circuit. Her speaker's bureau advertised Howe as the “author of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, and of many other well-known poems.” His client was available for serious lectures on social issues and discourses on philosophy as well as “comic entertainments.” She would even fill the pulpit for “Sunday services when desired.” There was strong demand among the 500 lyceums across the country.

And the “Battle Hymn” helped shape religious nationalism in Europe and North and South America in the nineteenth century. “Altar, saint, apostle, martyr, temple, ark, creed” — all of these words were used to speak of the nation-state in wars for independence and wars for national consolidation in places such as Greece, Poland, and the Crimea. During World War I, it was widely sung to emphasize an Anglo-American unity of purpose, and was nearly named the American national anthem.

The durability and success of the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" makes the most sense in the context of romantic nationalism and the philosophical idealism that accompanied it. Julia Ward Howe brought these two worlds together as effectively as anyone of her generation. The way the poem was formulated, how it was put to work, how it was in turn appropriated for wars and reform crusades of all kinds is best described as religious nationalism.

At the very least, "religious nationalism" more accurately names one aspect of the experience of religion in American life. Americans take pride in their institutional separation of church and state, no matter how much they might disagree about a "wall of separation" or whether the church is more a danger to the state or the state to the church. Innumerable books attempt to understand church and state in America. If, instead of church and state, officially separated for the sake of religious and civil liberty, we think of the relationship between religion and nation, a wider world of inquiry opens up before us. If Americans have honored and even strengthened the legal separation of church and state, they have rarely separated religion from nation. Americans on the whole have proven eager, on the one hand, to bring nationalism into their churches (witness flags at the front, the national anthem sung in worship, political sermons, and even the Pledge of Allegiance in the weekly order of service) and, on the other hand, to bring religion into their celebrations of the sacred nation called to do God's will in the world.

Portions of this essay appeared in the author's book, A Fiery Gospel: The Battle Hymn of the Republic and the Road to Righteous War, published recently by Cornell University Press.