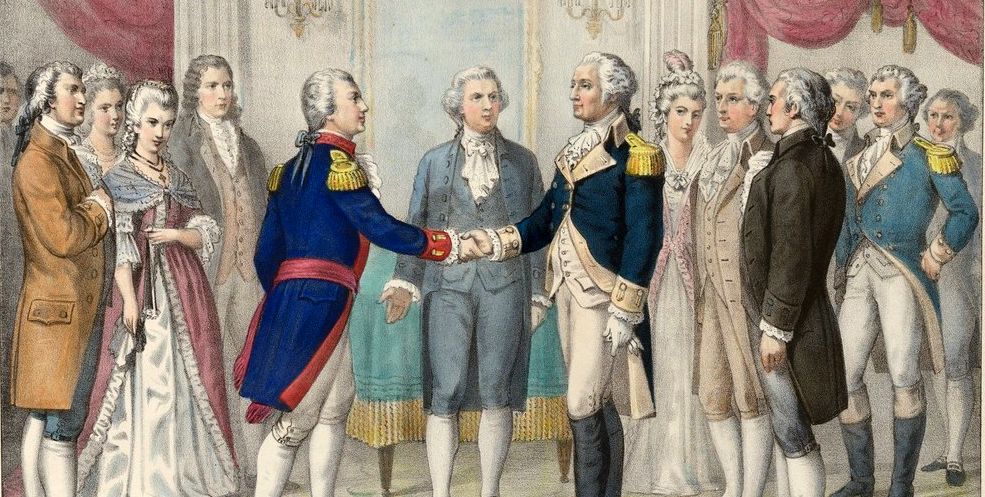

No figure in the Revolutionary era inspired as much affection and reverence as Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette

-

Summer 2021

Volume65Issue5

Editor’s Note: We were disappointed when individuals protesting racial injustice last May spray-painted monuments in Lafayette Park, as we wrote at the time, since the vandalized statues of Lafayette, Kosciusko, and Von Steuben depicted young revolutionaries who came to this country to fight for democratic rights. So for this issue we asked historian Harlow Giles Unger to remind us why the Marquis de Lafayette was so important in the early history of our nation. Portions of this essay appeared in his delightful biography, Lafayette.

“Pronounce him one of the first men of his age, and you have yet not done him justice,” reflected John Quincy Adams. Turn back your eyes upon the records of time . . . and where, among the race of merely mortal men, shall one be found, who, as the benefactor of his kind, shall claim to take precedence of Lafayette?”

With those words to Congress in 1834, Adams plunged America into deep and universal mourning. Lafayette was dead, and Americans mourned as they had never mourned before, not even when Washington had died, thirty-five years earlier. For no one in the history of the nation had ever given of themselves as generously or as freely as “Our Marquis.”

Lafayette was the last of the world’s gallant knights, galloping out of Arthurian romance, across the pages of history, to rid the world of evil. Of all the Founding Fathers — the heroes and leaders of the Revolutionary War — only Lafayette commanded the unanimous acclaim and veneration of Americans. For only he came with no links to any state or region; only he belonged to the entire nation; and only he, among all who pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor, sought no economic or political gain. He asked no recompense but the right to serve America and liberty, and, when Americans lost him, they knew that they and the world would never see his kind again — a hero among heroes.

An intimate and friend of world leaders over 70 years of earth-shaking social, political, and economic change, Lafayette led three revolutions that changed the course of world history and became the world’s foremost champion of individual liberty, abolition, religious tolerance, gender equality, universal suffrage, and free trade. He was arguably the wealthiest aristocrat in France, with close ties to the king, the royal family, and the entire court; his wife’s family was equally wealthy and well-placed. He and his family danced at Marie-Antoinette’s balls, hunted with the king, and glutted themselves at palace banquets in Versailles.

Yet Lafayette turned his back on it all — indeed, fled, from incomparable luxury — to wade through South Carolina swamps, freeze at Valley Forge, and ride through the stifling southern heat of Virginia — as an unpaid volunteer, fighting and bleeding for liberty, in a land not his own, for a people not his own.

Even the most selfless of his fellow Founding Fathers in America had some personal interests at stake. George Washington also refused compensation for his military service, but admitted that his initial motive for battling the British was his distaste for taxes: “They have no right to put their hands in my pockets,” Washington complained.

Lafayette had no such motives when he came to America in 1777. Only 19, he all but immediately proved himself a brave, brilliant soldier and field commander, admired and adored by his troops and fellow commanders. And when the American Revolution seemed lost, he sailed back to France to win what may be the most stunning and paradoxical diplomatic victory in world history — coaxing Europe’s oldest, most despotic monarchy into making common cause with rebels to overthrow a fellow monarch.

Returning with a huge French armada and thousands of French troops, Lafayette helped lead a brilliant military campaign in Virginia that climaxed with Britain’s defeat at Yorktown and earned him world acclaim as “the Conqueror of Cornwallis.”

Lafayette’s triumph in America, however, turned to tragedy in France when he tried to introduce American liberty to his native land and took command of the French Revolution. In releasing the French from their chains of despotism, he unwittingly unleashed a horde of beasts who plunged France and Europe into decades of unimaginable savagery and world war.

The despots of Europe — and the French themselves — punished him and his family horribly, sending him, his wife, Adrienne, and their two daughters to dungeon prisons and exile, and some of his wife’s family to the guillotine. America’s James Monroe saved the surviving family members, winning Adrienne’s release and helping Lafayette’s fourteen-year-old son escape to America and the safety of George Washington’s home in Mount Vernon. Ultimately, it was the courage of Lafayette’s brilliant, adoring wife who saved his name and some remnants of the family fortune.

Lafayette lived in two worlds, and his story is the story of both during the most critical period in Western political history. Born in the Old World, his spirit belonged to the New, and the revolutions he led in each changed the course of both: one spawned American democracy; the other became the uterine vessel for genocidal political ideologies — communism, fascism, and Nazism.

Lafayette was an intimate of the New World’s heroes and an enemy of the Old World’s villains. The savage Robespierre condemned him to death for treason, but Washington loved him “as if he were my own son,” and he called Washington “my adoptive father.” Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Quincy Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Nathanael Greene, Henry Knox, Anthony Wayne, and Benjamin Franklin were trusted friends. Schooled at Versailles with the future Louis XVIII and Charles X, he mingled as easily with Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, with Frederick the Great and William Pitt, as he did with his troops on America’s battlefields, where he won veneration as “the soldier’s friend.”

Over the years, grateful Americans have named more than 600 villages, towns, cities and counties, mountains, lakes, and rivers, educational institutions, and other landmarks for the great French knight who helped win their liberty. Ironically, not a single community in France has ever acknowledged his existence in this way. The isolated mountain hamlet of Chavaniac hyphenated his name to its own only after American philanthropists bought and restored the château where he was born, converting it into a museum and a source of income for surrounding communities. Paris named a street and a small square for him, and a department store took his name to identify its location on that street — not to celebrate him.

To this day, many in France call him traitor — especially radicals at opposite ends of the political spectrum — royalists, Bonapartists, and fascists on the right; socialists, communists, and anarchists on the left. For such extremists, Lafayette’s American-style republican self-government represents a threat to the absolute power they still seek — and the profits that power would put in their pockets.

The pervasive French distrust of Lafayette and the American ideals he took to Europe have colored not only many French biographies of Lafayette but also the works of American biographers who relied too much on their French predecessors instead of original documents. That reliance is easy to understand because there is so much original material available that most biographers simply cannot or will not read it all, and much of it is written in an older French that many Americans mistranslate so badly that they obscure or alter its meaning.

Lafayette lived an extraordinarily long life for his era — seventy-seven years — and participated in some of the most cataclysmic events in modern history: the American Revolution, the French Revolution of 1789, the abdication of Napoleon and the restoration of the French monarchy, and the French Revolution of 1830. He “reigned” over France twice in his life and personally enthroned a French monarch.

Not only did Lafayette compile his own voluminous memoirs, but both the French government and American Congress commissioned enormous compilations of every document each nation produced during the American Revolutionary War. The results were two massive works: five volumes, quarto, by Henri Doniol — Histoire de la Participation de la France a l’Etablissement des Etats-Unis d’Amerique — and six volumes, octavo, small type, by Francis Wharton — Revolutionary Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States.

Added to these two overwhelming works — and Lafayette’s own six-volume memoirs — are the endless multi-volume biographies, autobiographies, diaries, and collections of letters and personal papers of those who knew him intimately: Washington, Adams, Hamilton, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Gouverneur Morris, to name just a few whose works color the portrait of this complex man. In France, his doctor, his friends, his comrades in arms, political colleagues, enemies, and a host of others who knew him wrote biographies and autobiographies that portray their impressions of Lafayette. There is also the small jewel of a volume by his wife and his daughter — written in their prison cells — that details the tenderness, love, and devotion he lavished on his family. To this library must be added the countless eighteenth- and nineteenth-century histories and the political, social, and economic analyses written in France, England, and the United States.

Beyond the enormous mass of published books are thousands of pages of his correspondence, essays, and pronouncements, collected at various institutions in France and America — in the Library of Congress, the libraries at Cornell University and the University of Chicago, the New York Public Library, the archives of the French Foreign Ministry in Paris, the Bibliotheque Historique de la Ville de Paris, the Bibliotheque de l’Institut de France, the Bibliotheque Nationale, the Château de Vol-lore, and the Château de Chavaniac, Lafayette’s birthplace in Auvergne, in central France. Without a pilgrimage to difficult-to-reach places that helped shape his life, it is impossible to truly understand this complex aristocrat.

University of North Carolina professor of history Lloyd Kramer maintains that Lafayette’s modern biographers have made “cultural assumptions about human behavior [that] transform him into a psychological case that John Quincy Adams [an intimate of Lafayette’s for fifty year] would not recognize. Indeed, the ‘Lafayette’ that Adams described has more or less disappeared from history.” I believe that other intimates of Lafayette — Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and others — would be as hard put as Adams to recognize the descriptions of Lafayette that range from “naive,” in some biographies, to “glory-thirsty,” in others.

For Professor Kramer, these “generalizations . . . became questionable” while he “pursued the peculiar activity of a historian.” They were even more questionable for me, as a former journalist, when writing of a biography. Like Professor Kramer, I read all of Lafayette’s correspondence and the correspondence of others to him or to others about him — Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Adams, Franklin . . . and on and on. There is no need to interpret Lafayette’s personality, motivations, sentiments, maturity, or effects and influences on others — no need to imagine what he may have thought or what his motives may have been; no need for this imaginative interpretation or for psychological evaluation.

Everything about the man — everything he said and thought, along with his motives — is on paper, in writing, on hundreds of thousands of pages. An early (1930) bibliography listing all the works written by and about Lafayette at that time runs more than 225 pages. There is no need for guesswork — only legwork, objectivity, and a willingness to let Lafayette tell his own story and let those who knew him speak for themselves — without cynical interruptions and specious interpretations.

The man was what he and those who knew him best say he was. Everything he wrote about himself and the events in which he participated is consistent with what Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Morris, and many others wrote about him and those same events; together, his own writings and those of his contemporaries paint a clear, unambiguous portrait of Lafayette that needs no interpretation by later biographers who never knew the man.

John Stuart Mill, the English philosopher and economist who began a close friendship with Lafayette in 1820, characterized him this way: “His was not the influence of genius, nor even of talents; it was the influence of a heroic character: it was the influence of one who, in every situation, and throughout a long life, had done and suffered everything which opportunity had presented itself of doing and suffering for the right. . . Honor be to his name, while the records of human worth shall be preserved among us! It will be long ere we see his equal, long ere there shall rise such a union of character and circumstances as shall enable any other human being to live such a life.

As Professor Kramer points out, some 19th-century historians may well have been too romantic, but too many twentieth-century historians were so cynical that they not only distorted history, they so discolored the portraits of historic figures as to make them unrecognizable. Lafayette was a splendid man — brimming with passions and compassion, but tempered with a marvelous, self-deprecating sense of humor. He was, for example, balding noticeably when he reached an Indian outpost in the wilds of upper New York in 1784, and he calmed his wife’s anxieties by noting that “I cannot lose what I do not have.” His passions included a love of adventure, liberty, and the rights of man; loyalty to friends and devotion to his wife and family. The compassionate Lafayette reached out to the oppressed, the downtrodden, the helpless — even buying an entire plantation in French Guyana for one purpose: to educate and free its slaves.

Recent biographers, in my opinion, have deprived Americans and, indeed, the world, of essential knowledge about our nation by diminishing his importance and relegating him to the shadows of history — with, I might add, too many of our nation’s many other heroes. I hope this biography will help restore him to his rightful place as one of the great leaders in American history. It was he who assured our independence and justifiably earned the title of “hero” in the hearts and minds of America’s leaders and, indeed, all Americans—during the Revolutionary War and for more than a half-century thereafter—and they were not wrong in their beliefs. He was a giant among the Founding Fathers of our nation. He was “Our Marquis.”

At the end of Lafayette’s visit to America in 1824, President John Quincy Adams told him, “We shall look upon you always as belonging to us, during the whole of our life, as belonging to our children after us. You are ours by more than patriotic self-devotion with which you flew to the aid of our fathers at the crisis of our fate; ours by that unshaken gratitude for your services which is a precious portion of our inheritance; ours by that tie of love, stronger than death, which has linked your name for endless ages of time with the name of Washington. . . . Speaking in the name of the whole people of the United States, and at a loss only for language to give utterance to that feeling of attachment with which the heart of the nation beats as the heart of one man, I bid you a reluctant and affectionate farewell.”

“God bless you, Sir,” Lafayette replied, “and all who surround you. God bless the American people, each of their states and the federal government. Accept this patriotic farewell of a heart that will overflow with gratitude until the moment it ceases to beat.”