The farmhouse of General John Glover, one of the great heroes of the American Revolution, is scheduled to be demolished after July 1, 2024.

-

Spring 2024

Volume69Issue2

Editor’s Note: Nancy L. Schultz is a retired professor and chair of the Swampscott Historical Commission, which is working with other local partners to save the General John Glover Farmhouse. For more information, see SavetheGlover.org.

There is a good chance that the United States would not be a country today without John Glover. On at least three occasions, he and his elite Marblehead regiment from Massachusetts saved General Washington’s army. He certainly deserves what Thomas Paine demanded: “…the love and thanks of man and woman.”

Yet Glover’s farmhouse, the home of a founder of the U.S. Navy and the Marines, is facing demolition, which would dishonor this hero and, therefore, our country. Disregard for this important history is a sad symbol of the current American failure to honor the people and events that made our country. As Paine warned, “What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives everything its value.”

Glover’s contribution is not as well understood as it deserves to be. The turning point in the history of Essex County – the northeast corner of Massachusetts – came in March 1775. North Atlantic fishing was suddenly halted when a new economic sanction called the Fisheries Act took effect as part of the Restraining Acts that Parliament had imposed on New England’s rebellious colonists. The towns that depended on fishing and maritime commerce were effectively shut down.

Patriotic sentiment was easily stirred up to get enlistments from the ranks of sailors and fishermen. Before long, nearly 600 men, including seamen, tradesmen, merchants’ sons and laborers from Marblehead’s approximately 1,000 families (plus a few from nearby towns) had enrolled in ten militia companies.

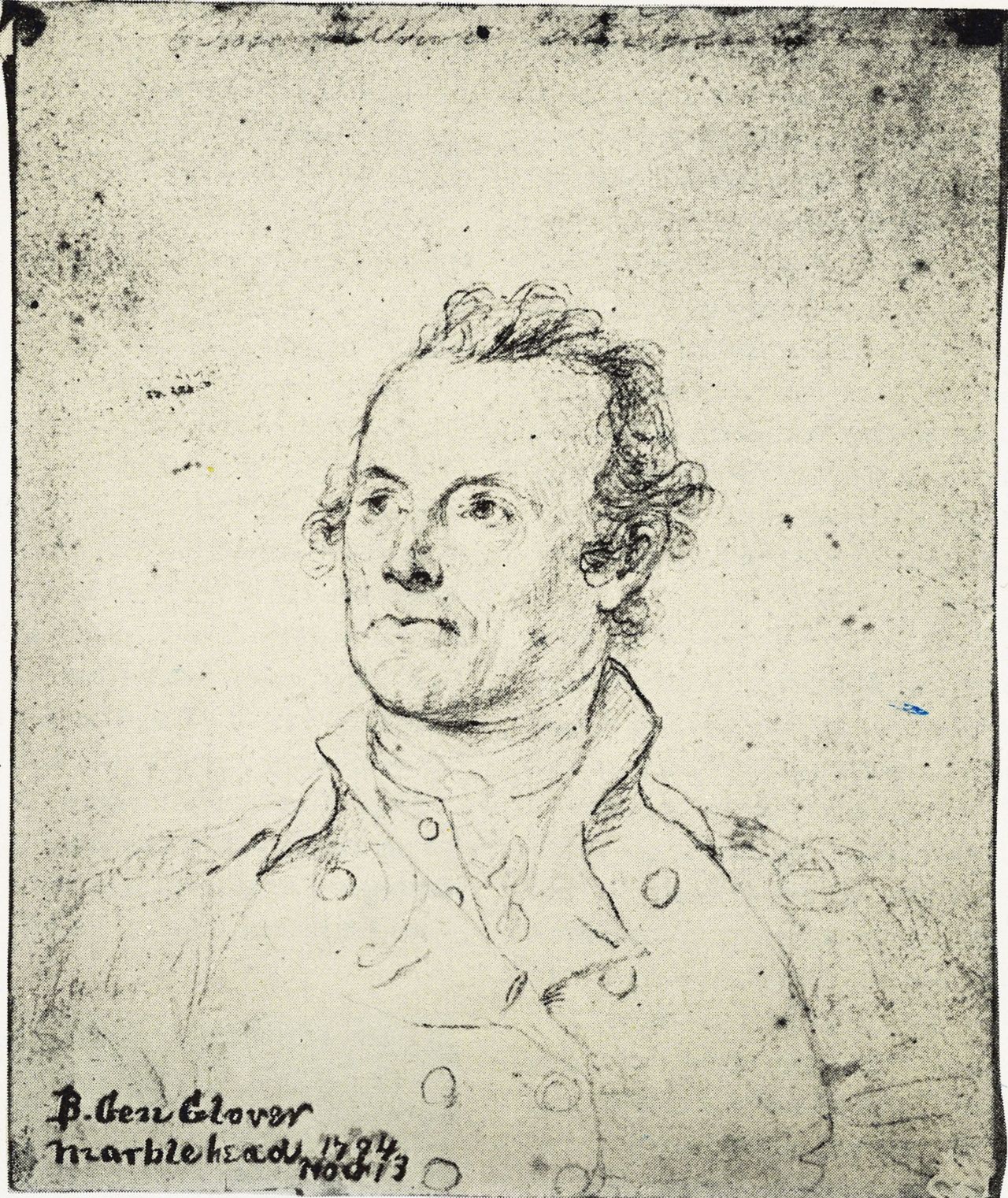

The Continental Congress put John Glover, a respected veteran of the French and Indian War, in charge of the Marblehead regiment and commissioned it as the Twenty-First Continental Army regiment. Some of the men were Spanish, Native American, Jewish, and African American, forming one of the first integrated units in the American service. They were also one of the most effective.

Glover outfitted ships to become privateers to harass British merchant shipping, and that small fleet was a forerunner of the U.S. Navy. In August 1775, Glover leased his own 78-ton schooner, the Hannah, to George Washington. Refit with cannon and swivel guns, Hannah was commanded by Marbleheader Nicholson Broughton and crewed by members of Glover’s Regiment. In the next few months, four other Marblehead vessels were leased, outfitted, and joined with Washington’s Cruisers, tasked with disrupting the British supply chain by capturing enemy vessels. These first ships of an American navy captured an astonishing 55 such prizes in six months, seriously disrupting the supply of British forces.

In the fateful year 1776, Colonel Glover’s amphibious regiment saved George Washington’s troops three times. First, in August, his men commandeered and manned boats to evacuate the Continental Army that was trapped on Long Island. Under cover of darkness, in a matter of hours, they ferried 9,000 men, plus horses, oxen, and cannon in rowboats across the treacherous East River, with the British warships only miles away.

Weeks later, General Washington left a brigade of 750 Marblehead men and three field pieces commanded by Glover to delay 4,000 British troops at Pell’s Point, in what is now the Bronx, allowing the main Continental army to escape.

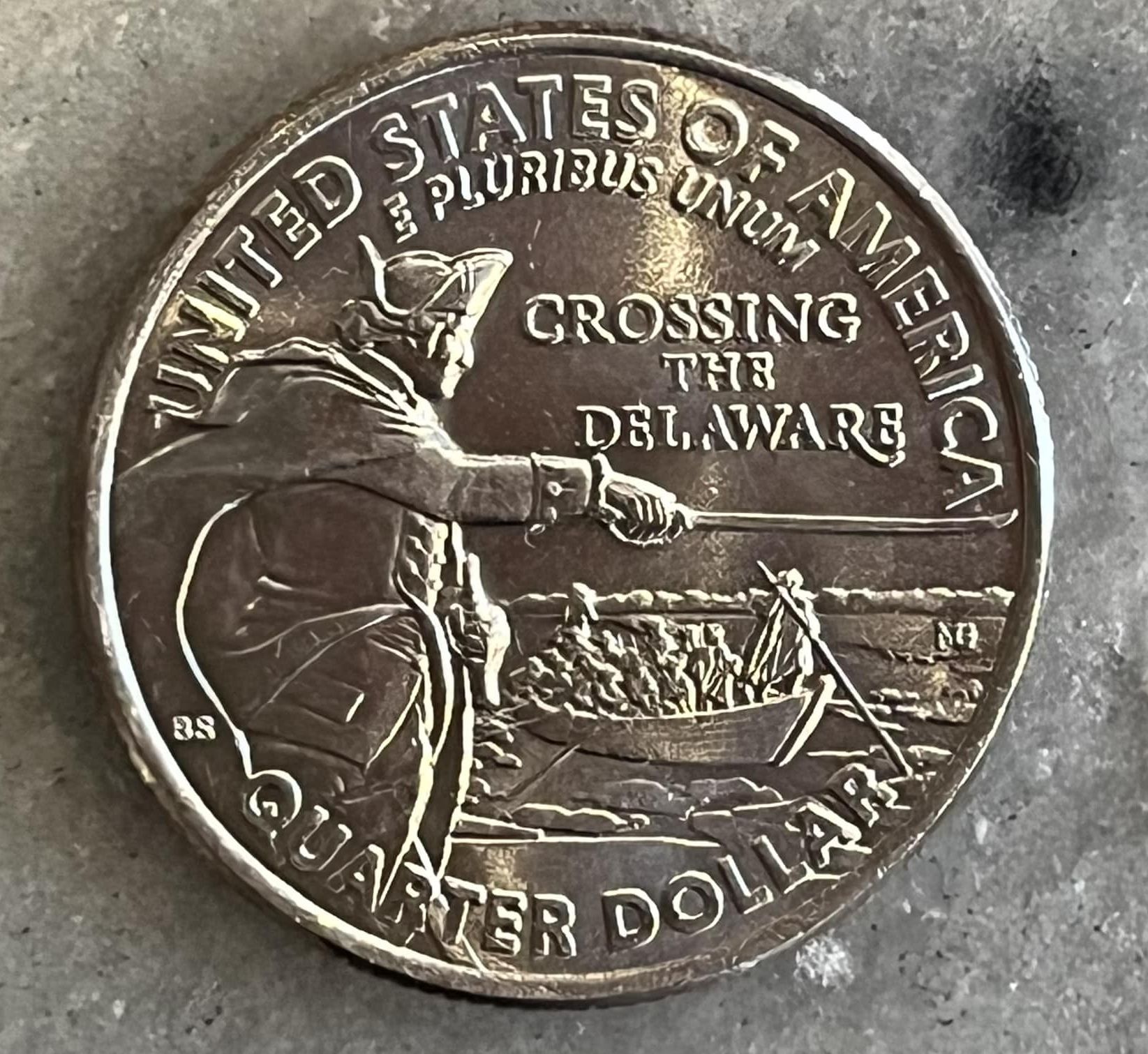

Then, on Christmas night in 1776, during a raging snowstorm, Glover’s regiment ferried 2,400 soldiers, artillery, and horses across the ice-choked Delaware River in 60-foot-long boats. They crossed the Delaware in the wee hours of the morning, marched nine miles to Trenton, attacked the Hessian garrison, took 900 prisoners, marched nine miles back to the crossing point, and re-crossed the river. The entire action took 36 hours.

In 1777, Washington promoted Glover to brigadier general, a role in which he excelled, despite devastating personal losses: the death of his wife, the loss of his eldest son in the war, and his own failing health.

The Last Home of an American Hero

The historic General Glover Farmhouse has stood for over 250 years on a uniquely shared site in Swampscott, Marblehead, and Salem, Massachusetts that has been occupied for centuries. Located near even older Native American settlements and the fort of the great leader, Nanepashemet, this land has been a crossroads for generations of inhabitants.

During the 1600s, the surrounding farmland was deeded to the Darling family. George Darling, a Scottish refugee, operated a tavern that sat on the Salem-Marblehead line in the late 1600s, prior to the construction of the Glover farmhouse. He left his house to his son, James Darling, who testified against Mary Towne Eastey during the Salem witch trials of 1692. It is believed that the Darling house vanished by the time that Glover’s farmhouse was built, but remnants of the old orchards remained.

The Glover farmhouse was built around 1750 on land located on the old Lynn Highway. This was one of the older colonial roads in Salem and Marblehead. During the 18th century, the house and farm were owned by William Browne of Salem, a prominent citizen and descendant of John Winthrop. He was a graduate of Harvard College and friend and classmate of John Adams. Browne was a colonel in the Essex County militia in Salem and a customs collector at Salem’s busy port.

Just before the American Revolution, William Browne accepted an appointment by General Gage as a judge on the Superior Colonial Court. Browne had become a British official, and, thereby, a Loyalist. He eventually fled with his family to Boston and then to England in 1776. The Massachusetts government confiscated all his property in 1780, including the house and farmland. The Banishment Act assured that William Browne would never return to Salem; in time, the Crown appointed him as the Royal Governor of Bermuda.

In February 1781, during his final year of military service, General John Glover purchased the farmhouse from the Massachusetts state government. He paid 1369 pounds for the house and 180 acres of land that spanned Salem, Marblehead, and what would later be Swampscott. Salem diarist Reverend William Bentley recorded that Glover used to say that he wasn’t quite sure what town he lived in, as the boundaries at the time weren’t well established, and one could literally step out his front door into another town.

John Glover moved with his second wife, Frances, and remaining family to the farmhouse in 1782 after retiring from the army. He wanted to escape the noisy, congested Marblehead waterfront where his town house was, and moved his business operations to the farm, as well. He lived in the farmhouse until his death in January 1797.

During his 15 years of retirement after the war, he worked to rebuild his shipping trade and served in elected offices, including six terms as a town selectman, as a delegate to the state convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution (1788), and as a two-term member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives (1788-1789).

During his 1789 inaugural tour of the United States, President George Washington made a special detour to Marblehead to thank the townspeople for their service and sacrifices during the war –– and, very likely, to see his former indispensable army officer.

John Glover died at the farmhouse on January 30, 1797, and was buried in the Old Burial Hill in Marblehead. His death is marked annually by Glover’s Marblehead Regiment, and his legacy is commemorated by various memorials throughout the region.

Glover’s name has been connected to the site for more than 200 years. In the early 20th century, the house was purchased by Alexander and Lillian Little. Mr. Little was the founder of the famed New England shoe manufacturer: A. E. Little & Co., located in Lynn, Massachusetts. The couple restored many of the 1700s colonial elements in the Glover House that had been built over in the past. They transformed the house into the General Glover Inn and Tea Room, as a way of profitably celebrating the general’s legacy. Many additions and outbuildings were added or renovated during this period, including a large barn that the Littles transformed into their home. The house of this renowned shoe manufacturer still stands on the site today, just behind the Glover farmhouse.

In 1957, the house became a well-known restaurant called The General Glover House. It was owned by Anthony Athanas, the founder of many eating establishments around the Northshore and Pier 4 in Boston. The house and restaurant were a focal point for generations of special events and community gatherings. While additions were built onto the frame of the historic house, the antique 1700s dwelling remained at its core, with many original interior features, including 18th-century doors, molding, chimneys, and fireplaces.

The General Glover restaurant closed in the mid-1990s, and the building has been vacant ever since. These separate eras of the house both before and after Glover’s time there each contribute to the site’s multi-layered history.

The Road to Threatened Demolition

In 2020, the town of Swampscott deemed 299 Salem Street “blighted” property because of the deterioration of some of the buildings, and attempted to impose a fine on the owner. In February 2021, the Select Board asked if the property should be condemned. In June 2022, a town meeting approved a zoning overlay on the site to allow development. That summer, discussions began about a proposed 140-unit housing complex to be called “The Glover Residences at Vinnin Square.”

The future developer claimed that the buildings on the site were so badly deteriorated that none, especially the house, could be salvaged. That fall, the Swampscott Historical Commission engaged in conversations with town administrators, the Planning Board, and the future developers to try to ensure that the site’s multiple histories would be honored.

An important turning point came in February 2023, when the commission was awarded a $6,100 Cultural-Sector Recovery for Organizations Grant from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. In March 2023, the commission made an initial determination that the house and site is “historically significant.” It voted to use the grant funds and its own budget to hire structural engineers for an assessment of the condition of the original Glover House.

The report confirmed that the mid-1750s house is still intact within the rambling structure of the former restaurant, and reported that a substantial portion is salvageable and can be restored as so many other historic buildings in similar, or worse, condition have been.

“Our consensus is that the original 18th century home can be restored and saved from demolition,” wrote Structures North Consulting Engineers, Inc. in their formal assessment of the house.

“The timber frame and much of the floor decking and roof sheathing of the General Glover House is in generally salvageable condition,” the wrote. “There are small pockets of framing that will need to be replaced or repaired, however, overall, the house is capable of being disassembled, reassembled and restored in an alternate location.”

Our commission held the required public hearing on April 13, 2023, and then, a week later, we imposed a nine-month demolition delay. This delay temporarily halted the sale of the property, which is contingent on all permits being received.

During the demolition-delay period, the commission made proposals to the future owner about ways in which the historic Glover Farmhouse could coexist on site as an asset to their new development to be named after the General. Incorporating historic buildings with new construction is absolutely feasible for this site and has been successfully accomplished in many other developments across the country. This idea, however, was rejected; the future owner indicated that they preferred to proceed with their plan to demolish all historic buildings on site, including the General Glover farmhouse.

The demolition delay expired on January 20, 2024, but the potential buyer has given assurances in writing that construction will not begin until after July 1. Along with the Swampscott Historical Commission, several partners from the towns of Swampscott, Marblehead, and Salem, including Glover’s Marblehead Regiment, the Swampscott Historical Society, historical commissions in Marblehead and Salem, and many others have banded together to save this historic home from destruction.

We must now come together and decide what is meant by this 250th anniversary of its founding. In a recent meditation on the deeper meaning of Emanuel Leutze’s iconic 1851 painting, “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” the rabbi Meir Soloveichik noted in the Wall Street Journal that “…in dramatizing the past, the work expresses aspirations for the American future.”

This sentiment crystallizes all the reasons we must save Glover’s final home. It’s not just that Glover was a great man, but that he understood that his integrated, disciplined, diverse seamen embodied the very idea of America for which the patriots were fighting.

Abraham Lincoln saw the same lesson in what Glover helped Washington accomplish at the Battle of Trenton. In his “Address to the New Jersey State Senate at Trenton” on February 21, 1861, Lincoln said:

The promise Lincoln referred to, of course, was the promise of America captured in Leutze’s famous painting. On the eve of America 250, will our citizens rededicate ourselves to the original idea that fueled this struggle? Can the United States still hold out great promise for the world? Will we honor our veterans by preserving tangible memorials of their lives? Will we save the General John Glover house so that future generations can also embrace the promise?

The author wishes to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Nick Curtis and Larry Sands. For more information or to donate, please visit www.savetheglover.org.