The World Trade Center attack wasn’t the first time New York was brutally assaulted — 225 years before, George Washington watched the city burn from his headquarters in northern Manhattan after painful military defeats.

-

September/October 2021

Volume66Issue6

Editor's note: Karin Abarbanel is the author of several nonfiction books. She grew up in Washington Heights just a few blocks from the Morris-Jumel Mansion. Now living in New Jersey, she enjoys visiting her old neighborhood and explores its colorful bygone history. She is currently completing her debut novel, a children's fantasy.

As we endure 9/11’s mournful 20th anniversary, many of us living in or near New York City in 2001 can still recall feeling compelled to seek solace in places both strange and familiar. Soon after the twin towers fell, I found myself drawn to a quiet corner of Manhattan some 11 miles to the north--about as far away from Ground Zero as you can get and still be on the island. There, nestled in a peaceful garden, stands the oldest house in Manhattan and one of its best-kept secrets: the Morris-Jumel Mansion.

A tiny acorn in New York’s vast forest of museums, this elegant, Palladian-style gem sits in hushed, aging splendor between 160th and 162nd streets in Washington Heights. Built in 1765 by a wealthy Tory who called his villa and estate, "Mount Morris," the museum is a 20-minute subway ride from midtown, but seems worlds away, a quaint echo of the city’s restless heart.

I hadn’t visited the museum's well-worn halls since I was a schoolkid at nearby P.S. 128, but rediscovered it a few weeks before September 11. After the attack, I found myself compelled to return. Ironically, it wasn’t just the mansion’s peacefulness that attracted me, but also its stormy past. Not the past of its most notorious resident, Aaron Burr, in whose bedroom Lin-Manuel Miranda wrote part of his musical, "Hamilton." Nor the flashy fifty years of its longest occupant, Eliza Jumel, reputedly once the richest woman in America. No, it was an uninvited guest who drew me uptown.

“Yes, George Washington did sleep here,” proudly proclaimed the museum’s canvas tote bag. And it's true: Washington commandeered the Tory mansion for five weeks in September and October of 1776 as the British invaded New York, even then the commercial hub of America. During his stay uptown Washington won his first victory. But he also endured crushing defeats--some of the lowest points in his command.

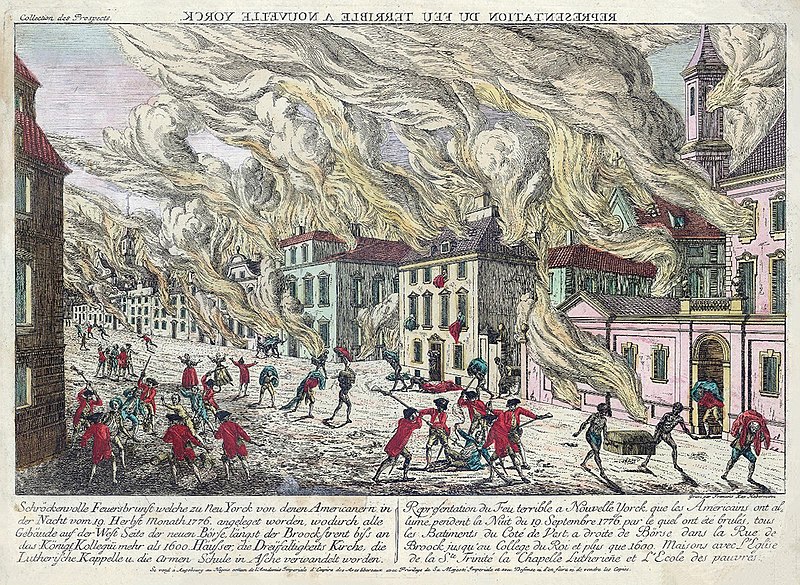

September of 2001 wasn’t the first time New York was brutally assaulted. In September of 1776, an eerily similar set of events occurred: surprise enemy attacks, acts of extraordinary courage by ordinary citizens, and a devastating fire (likely set by patriots to impede the British), which raged across Lower Manhattan for days and reduced one-third of the city to ashes.

Washington’s choice of the Morris mansion as his headquarters was no accident: It stands on one of highest points in Manhattan–so high, in fact, that Washington watched New York City burning from the estate’s grounds on September 21, 1776. It was from this vantage point, 225 years later, that the museum’s staff and a handful of French tourists watched the twin towers blaze and crumble.

Not long after 9/11, I retreated to the mansion and sat on a bench in its peaceful garden. Washington’s presence seemed to infuse the amber sunshine. In the wake of the terrible assault New York had just suffered, it felt deeply consoling to think of his strong, resolute spirit hovering over Manhattan and embracing the wounded city.

As I struggled along with everyone else to absorb the horror at the other end of Manhattan, I couldn’t help but wonder if this small, serene refuge could offer any comfort to the city that had sheltered it so long. Another attack on America! Surely, Washington’s spirit must be quaking with rage! What better place to invoke it than here?

It turned out that Ken Moss, the museum’s director at the time, was asking much the same question. He'd worked hard to make the mansion a vibrant part of the city's buzz and bustle, boldly billing the octagonal parlor where Washington once played cards and listened to music as the “oldest performance space in Manhattan." Still, it was easy to feel cut off from the rest of the city and the devastation downtown as Ken and I met at the mansion one afternoon to reflect on September 1776 in the harsh light of September 2001.

We sat a stone's throw from Washington's green office-bedchamber on the second floor. By no means the largest bedroom in the mansion, it offered the most privacy, a luxury Washington always sought when traveling with his large “military family.” During his stay, the hallway by his door would have been well-trafficked day and night as the general's small army of aides, secretaries, and bodyguards raced to and fro with news from the front–most of it bad.

After abandoning Boston, the British began massing for a huge assault on New York. In July and August of 1776, nearly 500 ships crowded the city's harbor, packed between 32,000 and 35,000 seasoned and well-heeled British and Hessian soldiers. Washington had an army of no more than 20,000 men, many of them ill and untrained, not a single warship, and an impossible task: defending a vulnerable city and miles of unprotected shoreline.

By September 7, the British army was advancing briskly up the East River. On September 10, its troops were poised to attack New York, then located in Lower Manhattan. An anxious Congress ordered Washington to hold New York “at all costs.”

Through Ken Moss, I was given brief access to the museum's collection of Washington's papers for September and October of 1776. Defeat. Defeat. A frail victory. More defeat. This cycle of military lows and highs is played out, not just on the battlefield, but on the page as well. This was a war, Ken Moss observed, that was fought as much with the pen as with the sword. Reading the avalanche of correspondence Washington sent from Mount Morris, you’d think he never left the house or slept a wink.

There are letters to friends, family, and the Continental Congress, along with the peppery General Orders that Washington issued daily to his troops. Staggering in scope, these documents offer a fascinating glimpse of every military engagement, including Washington’s unsparing postmortems. Painfully detailed as well are the overwhelming obstacles he saw himself besieged by in his fight to save New York. There were logistical logjams, supply shortages, plunder and pilfering, Congressional crises, deserters, disease, and death – and that was on a Monday.

In light of the ashes and death at Ground Zero, it felt almost surreal to sit at the other end of Manhattan in the museum’s attic library above Washington’s bedroom and see a blow-by-blow account of Washington's defense of New York. Consider his General Orders of September 19 in which he tells his men, “We see, we know that the Enemy are exerting every Nerve, not

only by force of Arms, but the practices of every Art, to accomplish their purposes….” Or Washington’s warning to John Hancock: “It becomes evidently clear, then, that as this contest is not likely to be the Work of a day…the War must be carried on systematically….”

On September 11, 1776, with a deep sense of foreboding that proved well-founded, General Nathanael Greene, Washington’s most trusted advisor, pleaded with him to surrender the city. Washington resisted. On September 12, he called a council of war. One by one, 10 of the 13 officers attending voted to abandon Manhattan.

Knowing that Congress desperately wanted New York protected, Washington defied his officers' advice. Instead of ceding the city, he chose to defend it. He gathered his forces and moved to higher ground and Mount Morris, the abandoned mansion of Roger Morris, a wealthy Tory colonel who'd fled the city.

The mansion was the centerpiece of a lush 135-acre estate. Its grounds once spanned the width of Manhattan, from the Harlem River to the Hudson. The estate offered a breathtaking 360-degree view of the city below, making it the ideal command post during Washington’s ill- fated, but spirited defense of Manhattan.

On September 14, Washington had left his first headquarters in what is now Greenwich Village. Moving northward, he reached the Morris mansion by late evening. One hopes he caught a good night’s sleep there, because the British attacked the next day.

By noon, five warships off Kips Bay let loose an enormous barrage, pounding the shoreline cliffs; barges unloaded 4,000 British and Hessian troops. As a young British sailor on the Orpheus recalled, “a tremendous fire was kept up.” In an hour, his ship fired 5376 pounds of powder, uprooting trees and boulders, and causing chaos on shore.

To his “great surprize and Mortification” as Washington later wrote, he watched as his troops “ran away in the greatest confusion without firing a Single Shot.” Galloping over during the fray, he began beating his terrified soldiers with his riding crop. Fuming, he threw his hat to the ground and cried, “Are these the men with whom I am to defend America?”

Washington then turned and faced the British alone, not moving an inch as 50 enemy soldiers marched toward him. If his aides hadn’t surrounded their beloved commander, it’s likely he would have been killed and the Revolution might have ended on the spot. One can only imagine Washington’s agitation as he returned to the Morris mansion that Sunday, shadowed by his sweaty palmed, nerve-wracked young officers.

Did he fall exhausted into his featherbed dreaming of Martha and Mount Vernon? Did he brood over his latest humiliation at the hands of the British, nursing a glass of old Madeira to ease his pain? Did he order a hasty supper before planning a counterattack? Or dash off yet another fire-breathing dispatch to Congress bewailing his green and wayward troops?

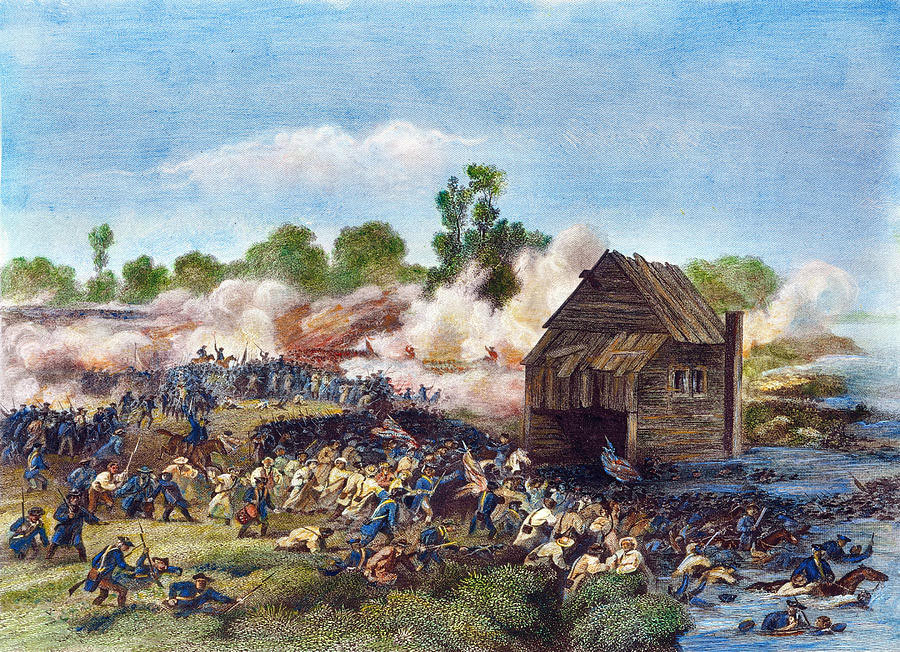

However he spent the night, at dawn, Washington and his men rose to fight again. Surprised by a British patrol, a small scouting party of Connecticut Rangers, some of whom had panicked just 24 hours before, stood their ground and fought for 30 minutes. The British rushed in reinforcements, among them Highlanders famed for their refusal to retreat. The Americans fell back. A British bugler blew the final call of the foxhunt, contemptuously signaling a victory.

Enraged, Washington sent out a small flanking force of sharpshooters. Stealing through the woods to a rocky hillside, they counterattacked. This time, it was the redcoats who ran, scrambling across a buckwheat field as the ragtag Continentals chased them to what is now 105th Street and Broadway.

The Battle of Harlem Heights, as this September 16, 1776 encounter is now called, proved to be Washington’s first combat victory of the Revolution. It also marked the first time his soldiers forced the British to retreat, not by attacking them from behind trees or walls, but by battling them in the open field. “The affair …seems to have greatly inspirited the whole of our troops,” Washington informed Congress.

It seems to have “inspirited” Washington as well: “…there were smart Skirmishes…” he wrote his brother, John. “In these the Troops behaved well, putting the Enemy to flight in open Ground….” His newfound hope was short-lived. On September 21, less than a week later, Washington watched helplessly from the grounds of Mount Morris as the British captured New York and fires engulfed the city.

More terrible news soon followed. Nathan Hale, a young Connecticut Ranger, was captured with notes on British fortifications hidden in his shoe, “encoded” in Latin. On September 22, he was hanged as a spy in an apple orchard and his body tossed into an unmarked grave. Hale’s heroic words, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country,” would have been lost forever had they not been brought to the Morris mansion under a flag of truce by a sympathetic British officer. Deeply moved by Hale’s quiet courage, the officer honored a promise to carry the young schoolteacher’s dying message to his fellow soldiers.

Lurking among the sick counts and losses Washington faced in New York are generous dollops of fear and anxiety. One letter to his cousin Lund, sent from “Col. Morris’s on the Heights of Harlem" on September 30, 1776, just a week after Nathan Hale's hanging, is especially poignant and dispirited. In it, Washington unleashes a Job-like wail that could easily have been heard across “the pond” by King George:

…such is my situation that if I were to wish the bitterest curse to an enemy on this side of the grave, I would not put him in my stead…I see the impossibility of serving with

reputation or doing any essential service to the cause by continuing in command; and yet, I am told that if I quit the command inevitable ruin will follow… In confidence I tell you that I never was in such an unhappy state since I was born.

Yet soon after penning these words, Washington rallies. He stops blaming circumstances and tells his cousin Lund exactly what he intends to do:

"And if the men will stand by me … I am resolved not to be forced from this ground while I have life."

His despair seemingly released and his decision made to stand fast if his soldiers do the same, Washington then launches into a passionate discussion of his chimney repair plans at Mount Vernon. What a mood swing! At a stroke, he abandons the depths of soul-defying anguish for the crisp autumn air and rooftops of Virginia!

Where did this astonishing ability to recoup, recover, and press on despite all odds spring from? How did he fend off defeat and discouragement so early in the war? Knowing precisely when to stand his ground and when to retreat was one skill Washington appears to have begun mastering at the Morris mansion.

Washington seems to be fashioning, in mid-crisis, his own personal recipe for resilience, for coping with misfortune and his own fears. Taking a stand and supporting it with every ounce of your being–that’s the first step in surviving life’s battles. Second, and equally important, is knowing when to fall back, whether from advancing redcoats or self-doubt. Mastering the rhythm of hope and despair, and knowing just how much of each to indulge in–what better definition of resilience can there be?

"And if the men will stand by me…” As Washington wrote this, he may well have been thinking of the “Bold and resolute” way in which his men had stood their ground just two weeks before in their "smart Skirmishes" with the enemy. More than likely, he would also have recalled his decision to withdraw his troops just when they had the British on the run and were hell-bent on pursuing them.

In that crucial moment, Washington realized what his men could not: that if they risked too much, the British would pour more troops into the fray and his army would lose the advantage it had gained. Small though it was, that advantage was enough to be the measure of victory. Redefining, not just the rules of engagement, but what winning meant from battle to battle was central to Washington’s success in wearing down a formidable ”Enemy”-- a strategy that began taking shape in New York at Mount Morris.

Despite his anger and anxiety, Washington dips his quill into the inkpot of hope. On the page, he gathers his grit—his courage and resolve—and commits to the long game. As he told John Hancock, prevailing over the odds he and his army face will not be “the Work of a day.”

He must carry out his plans systematically in spite of shortages of men and supplies, a panicky Congress, a ruthless foe, and overwhelming odds. He begins to discern and accepts the cycle of bitter losses and precarious wins that he and his men, standing together, will endure. If

they stand fast, so will he. On Mount Morris, he learns how to proceed beyond loss, to maintain hope and momentum in the face of defeat.

In October, two weeks after Washington's letter to Lund, his army was attacked again. Feverishly digging into the rocky cliffs overlooking the Hudson, soldiers cobbled together the battlements of Fort Washington. As his men scraped the obstinate earth, Washington spent long, restless hours trying to anticipate the strategy of his “Enemy.” Putting on his diplomatic hat, he also wined and dined two Native American chieftains at the Morris mansion, showing them “every Civility,” and “all his works upon the island” to convince them of his army’s strength.

By October 21, Washington was forced to retreat from the Morris mansion and direct his battle plans from White Plains. On November 16, the British launched the Battle of Washington Heights, an earth-shattering attack pitting 8,000 troops against fewer than 3,000 Continentals. Warships pounded Fort Washington from the Hudson River. Artillery blasted it from the land. A valiant troop of 150 sharpshooters held back 850 Highlanders, but in the end, it was a total rout.

During the attack, Washington and some of his senior officers made their way back to the Morris mansion, where they watched the bloody battle unfold, escaping only minutes before British soldiers captured their former headquarters. Within hours, Fort Washington fell. Watching from across the river at Fort Lee, as many of his men were slaughtered or captured, Washington is said to have wept.

By late afternoon on November 16, the battle was over. The American flag was lowered. Captured Continental soldiers were force-marched to Lower Manhattan. It was the biggest defeat of the seven-year war. Yet only six weeks later, Washington followed the worst loss of his military career with his stunning “retreat to victory” through New Jersey, where he waged and won two pivotal battles in Trenton and Princeton.

On September 11, 1776, George Washington chose not to abandon New York--to stand and fight in the face of overwhelming odds. On September 21, he saw much of the city go up in flames. In November, his army was defeated and desperately needed soldiers captured. He lost his battle to save New York. But in his time at the Morris mansion he began to shape a strategy suited to his circumstances--a way of fighting that will ultimately wear his enemy down. He learned what he needed to know to survive and succeed.

For the rest of the war, New York remained in enemy hands. Lower Manhattan served as Britain’s central prison camp. In all, some 11,000 Americans perished from malnutrition, disease, and mistreatment in jails and on ships moored in New York Harbor and Brooklyn–three times more than were killed in all the battles of the war.

The Morris mansion was used by both the British and Hessians as their headquarters. In 1790, it enjoyed a brief flash of glory when Washington returned as President for a commemorative dinner, along with members of his cabinet and their wives. Sitting with

him at the sumptuously appointed table where he once plotted war, were John and Abigail Adams, John Quincy Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton.

Now that the COVID-19 restrictions are easing and museums are open, I plan to catch the A train up to the Morris-Jumel mansion. I'm looking forward to sitting in its lovely garden, gazing up at the mansion's pleasing, harmonious lines, and strolling its spacious halls once again. Surely, it's no small miracle that this peaceful place, built of ancient wood and broken Tory dreams, and alive with American courage and resolve, still survives.

But it's not just peace I'm after. In the shadow of the pandemic, on the heels of a painful anniversary, with turmoil everywhere, as we struggle with problems that threaten to divide and conquer us, I'd love to catch a wisp, a glimmer, an inspiriting flash of the "Old Fox," as the British called Washington. To feel that he's still around, I have hope.