In “the cradle of the American Revolution,” loyalists to the Crown faced a harsh choice: live with terrible abuse where they were, or flee to friendlier, but alien regions.

-

Spring 2024

Volume69Issue2

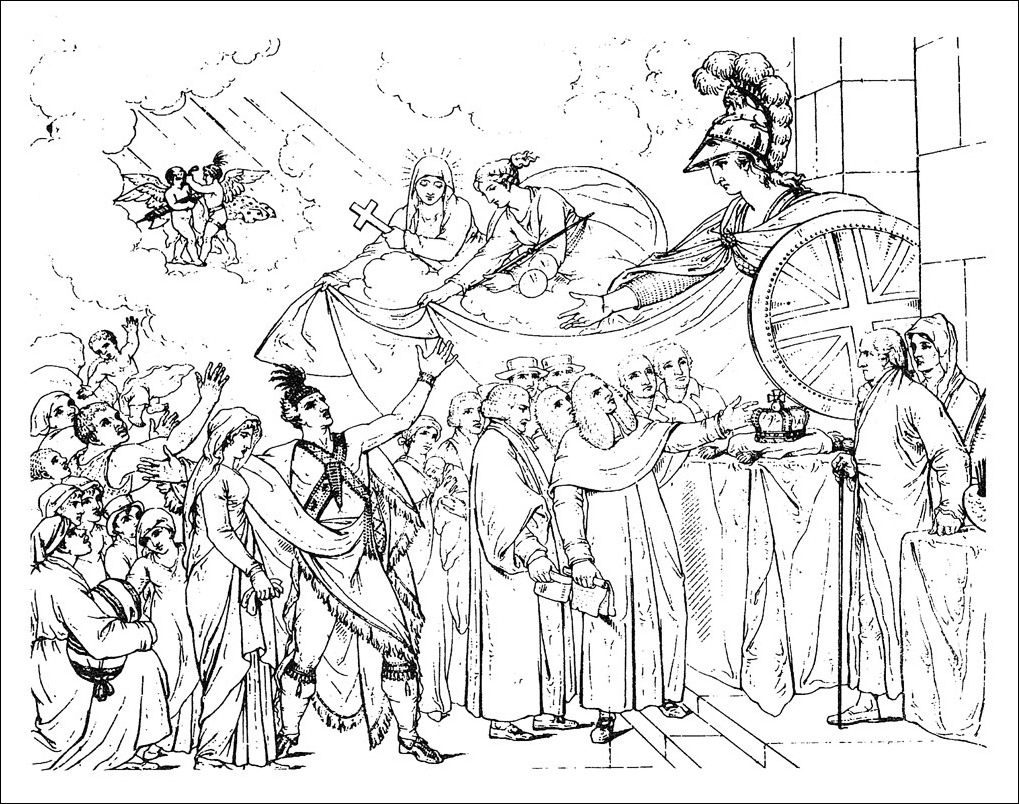

It has been said that history is written by the victors, so it is not surprising that the story of Loyalists who lived in the American colonies and held fast to their loyalty to the Crown is not as widely known as that of the Revolutionary War’s victors. In many ways, Loyalists suffered not only the slings and arrows of their Patriot neighbors as the drumbeat to independence from England grew louder and louder. Many Loyalists suffered the agony of fleeing their towns and homes for another country. Historian Thomas B. Allen characterized the Revolutionary War as “America’s first Civil War.” By the end of that conflict, between 60,000 and 100,000 people fled their homes in the colonies.

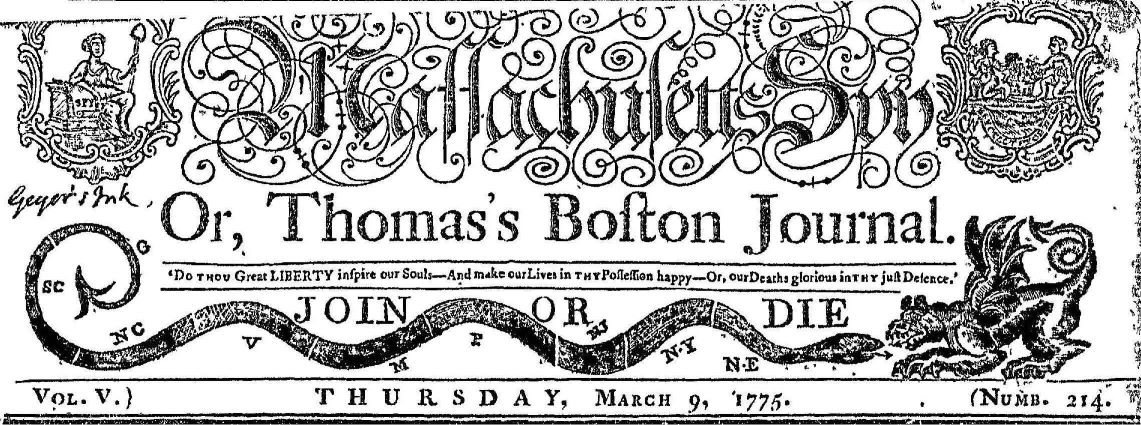

Before the outbreak of that war, the tumult was already reaching up and down the eastern seaboard. It was most contentious, though, in what several historians have called “The Cradle of the American Revolution,” Massachusetts. From Boston’s furious streets into the Massachusetts colony’s hinterlands, whether originating with individuals or stimulated by local Committees of Correspondence (formed to exchange information and ideas within and among the several colonies and, later, with local Committees of Safety that coordinated military and security issues), antagonisms ran hot and heavy among the populace.

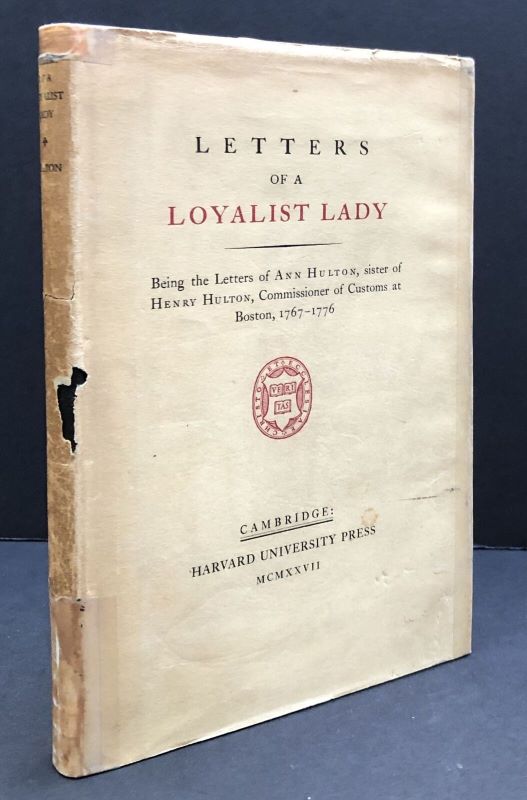

Loyalist Ann Hulton wrote a friend a letter on September 4, 1767 from her home in Brookline, Massachusetts (a town of about 600 people surrounded on three sides by Boston) that promised “many things to tell you, & some very interesting events I must communicate . . . .” This and later letters were collected in a book, Letters of a Loyalist Lady, which wasn’t published until a century and a half later. In addition to reflecting upper-class life (her brother Henry, who lived with her, was the Crown’s Commissioner of Customs in Boston) during a particularly fractious period in colonial America, the letters offered a firsthand view by a fervent Loyalist.

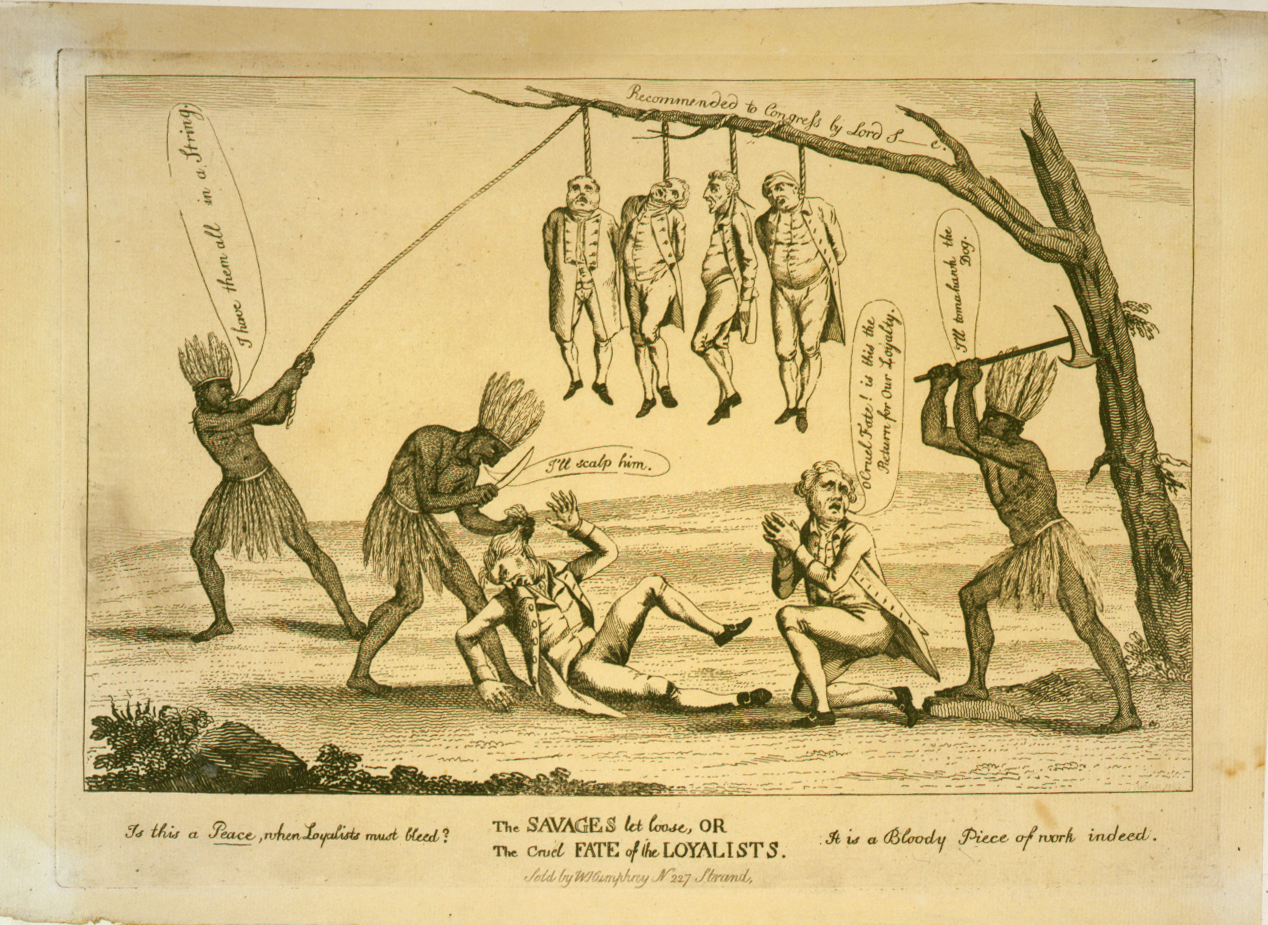

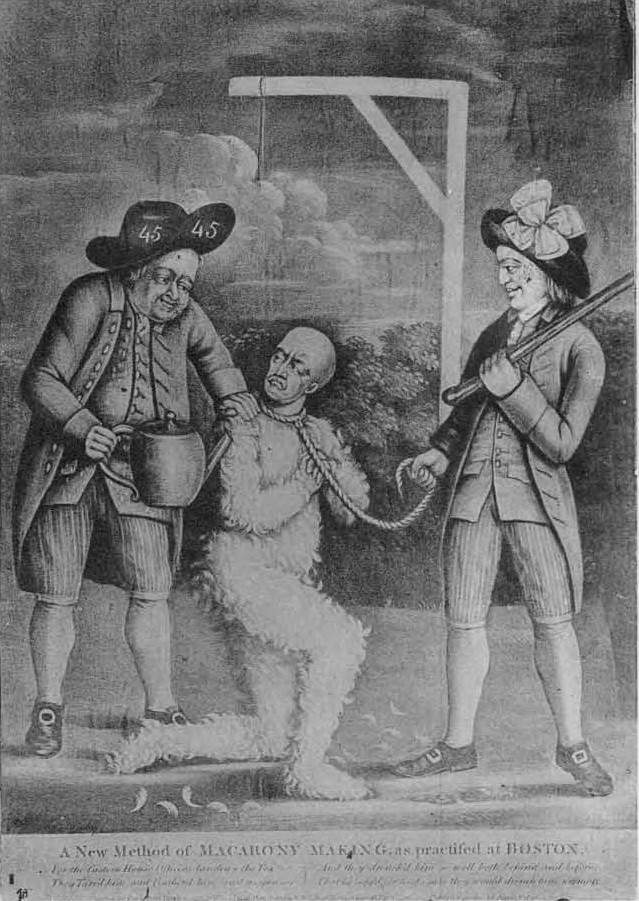

By 1776, the Hulton siblings had had enough of the tensions in their colony and bolted for England’s friendlier shores. Ann wrote in one of her letters that, during her family’s stay in Brookline, “ruffians” armed with swords and pistols had broken into their house, smashed windows, and beat and shot at them. She detailed the tarring, feathering, and whipping of a Loyalist customs officer and wrote of a “Tory woman” being treated with “great rudeness and indecency” by rebels who stripped her and her children of their clothes. Similarly angered at the colony he was leaving behind, brother Henry described rebellious Massachusetts Patriots as “banditti of the country; amongst whom there is not one that has the least pretension to be called a gentleman. They are a most rude, depraved, degenerate race, and it is a mortification to us that they speak English, and can trace themselves from that stock.”

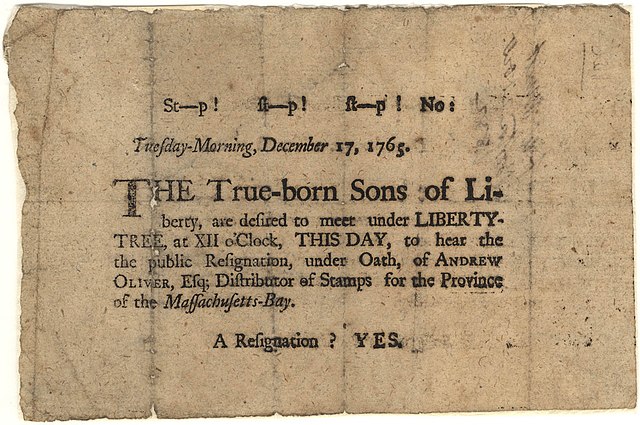

During the Hultons’ time near Boston, revolutionary fervor had amplified. The Sons of Liberty were protesting import and other taxes, crowds were lynching and burning effigies of disfavored figures, and rival mobs were clashing. One night in 1770, revved-up Patriots broke into the mansion of royal lieutenant governor Thomas Hutchinson and nearly demolished it. British soldiers fired into a rock-throwing mob, killing three and fatally wounding two in what came to be called the Boston Massacre.

Although thousands of Loyalists left the American colonies before, during, and after the Revolutionary War, many remained. Some, forced under duress to take loyalty oaths, stayed in their towns and villages. Others, out of practicality, continued with their businesses or farms. And, whether genuine or feigned, some professed acceptance of the Patriot cause. To remain loyal to the Crown posed a harsh choice: live with scorn where they were or flee for friendlier, but alien regions. Loyalists felt deep attachment to the mother country and the Crown. Some of them held tight to the sovereign as head of the Anglican church and to the tradition of parliamentary monarchy, while others focused on family prominence, trading connections, power, prestige, and their dread of civil war.

As for the Patriots’ motivations, there was the ambition for a new order that rejected the Crown’s ever-increasing restrictions and taxes; resentment of a royal ban on settlements west of the Appalachians; rising duties on sugar, textiles, and coffee; and the outlawing of colonial currency. Religion, too, was a wedge. “Virtually every Anglican clergyman in America became a Loyalist, and Presbyterians were labeled Rebels,” wrote the historian Thomas B. Allen. Intolerance became the norm. “To such a point of madness have the people arrived that we are now forbidden not only to speak but to think,” one Massachusetts Loyalist said.

Massachusetts was not alone in experiencing such friction. New York City, Philadelphia, the Carolinas, and Georgia were Tory strongholds, as well. Why did Massachusetts come to be known as “The Cradle of the American Revolution”? The simple explanation might be the colony’s profuse communications networks and its ability to spread news rapidly. With each Crown crackdown and Patriots’ often violent reactions—the 1765 Stamp Act, the 1767-68 Townshend Revenue Acts, the military occupation of Boston beginning in 1768, the Boston Massacre in 1770, the 1773 Tea Act, and the 1774 Coercive Acts (a.k.a. the “Intolerable Acts”), colonists were increasingly at one another’s throats. Imposition of the Intolerable Acts cast Loyalists as foes of a country careening toward independence.

Such was the vitriolic tension between Massachusetts Patriots and Loyalists—who, following the sobriquets of those of like mind across the Atlantic, also went by “Whigs” and “Tories”—as Americans approached rebellion. In 1778, after war had broken out, Massachusetts passed the Banishment Act of the State of Massachusetts, “an act to prevent the return to this state of certain persons therein named, and others, who have left this state or either of the United States, and joined the enemies thereof." Some 308 Massachusetts Loyalists, including former officials of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, were specifically named in the act as banished from the province.

The tumult spread from Boston’s furious streets into the colony’s hinterlands. In Plymouth County, for example, Daniel Dunbar, “of Halifax, Massachusetts, gentleman, was from infancy loyal to the King and the British Government.” He served as a second lieutenant in the Crown militia at Halifax, Nova Scotia. In 1774, a mob broke into his house, dragged him out, and beat him. He left for refuge in nearby Boston. When the British withdrew from the city on March 17, 1776, he sailed with the Royal Army back to Halifax. Massachusetts banished him.

That same year, Daniel’s son Jesse bought cattle from a Tory. He had slaughtered and skinned one of the animals when Whigs, intent on teaching him a lesson about dealing with the enemy, set upon him. His tormentors tied him to the dead cow’s belly, put the two of them in a cart, and drove four miles to neighboring Duxbury, where another mob took over. Some of the horde used the cow’s stomach to thrash Jesse’s face. The rioters then took Dunbar’s money and left him to find his own way back home.

In 1770, a merchant named Ebenezer Cutler of Oxford in Worcester County tried to run two wagonloads of boycotted English goods out of Boston under cover of night. A crowd of indignant citizens, alerted by a night watch, pursued and overtook him and forced him to return to his home with the items. A little while later, the local Committee of Correspondence impounded the goods. In a case handled by John Adams, who represented Cutler in some of his court cases, two of the people present that night were sued by Cutler, who sought £5,000 in damages for assault, false arrest, and other “enormities.”

Although he won his case in the Worcester Inferior Court, a trial on appeal in Superior Court of Worcester found for the defendants. A writ of review filed a year later again cleared one of the defendants, but found the other liable—but for only £15. In a final act of retaliation, in 1775, the Worcester County Committee of Correspondence in nearby Northborough accused Ebenezer Cutler of speaking “many things disrespectful of the Continental and Provincial Congresses, acting against those bodies’ resolves, offering to assist British General Thomas Gage, and other traitorous activities.” Fearing for his safety, Cutler fled to Boston, departing “without his effects.” The next year, he accompanied the British army to Nova Scotia and settled there – another Loyalist banished by his home state.

Attorney Daniel Bliss of Concord made no bones about his bent. Royal Governor Hutchinson named Bliss a Justice of the Peace, commenting that he was a very active Tory. When neighbors learned that British army officers were visiting Bliss to assess the town’s preparations for rebellion, they threatened to kill him and the Britons. Bliss fled, later sending his brother Samuel to spirit away his family and save what they could of his holdings. But to no avail: the Public Record Office in London, England has a copy of a complaint against his estate signed in 1780 by John Hancock and John Avery, Jr. which resulted in the forfeiture of Bliss’s property. The Loyalist joined General John Burgoyne’s army, assuming an important position in the Niagara region. At war’s end, he settled in New Brunswick, Canada, where his legal work brought him prominence. Meanwhile, Massachusetts banned him from returning, upon penalty of death.

Nathaniel Ray Thomas was a Loyalist leader in Plymouth County’s Marshfield, the only Massachusetts town openly faithful to the British legislature and the Crown. In 1774, Mr. Thomas welcomed 100 British soldiers to quarter on his estate, moving his own family that winter so as to accommodate the troops. Resulting threats from surrounding towns drove Thomas away, along with about 200 Loyalist neighbors. Attaching himself to Crown forces, he served in Nova Scotia and New York before fleeing to England in late 1777. The Public Record Office in London preserved a tribute to the town of Marshfield’s dutiful deportment: “... through a ten years’ political struggle and warfare, the town never deviated from, but had uniformly and invariably preserved and maintained its Integrity and Loyalty; a Town, the only one in New England, that, in spite of the threats and intimidations of surrounding Towns, counties, and Provinces, dared, publickly and collectively to own and acknowledge their Allegiance, and the Supremacy of the British Legislature.”

Women, too, suffered for their Loyalist convictions. Many were exiled or just left voluntarily. Anna Borland, wife of John Borland, Esquire, of Braintree, Norfolk County, fled with her spouse and their nine children to Boston in 1774, seeking the protection of Crown forces. John died in 1775. To keep her sons from being pressed into the “rebel army,” Anna sailed first to England and later to Tory-friendly New York where she felt she might have “. . . more speedy communication with those who may be disposed to relieve her.”

Jane Gordon, the widow of Boston merchant Alexander Gordon, sought British army commissions for three of her sons so they didn’t have to serve with the despised Patriots. She aroused further enmity among her neighbors by nursing British officers who had been wounded at Bunker Hill. In 1775, she left Boston for Nova Scotia and then England, settling in Edinburgh, Scotland, where she died in 1789.

The Loring family were staunch Loyalists whose patriarch, John the Elder, had been a captain in the Royal Navy and later sheriff of Suffolk County, Massachusetts. Elizabeth, the 25-year-old wife of his son Joshua, romanced William Howe, commander-in-chief of British land forces in the colonies. Described as a playful, blue-eyed blonde, she was Howe’s constant companion as he gambled and drank the nights away. Some said that Howe paid more attention to Mrs. Loring than to the war he was prosecuting; his strategy and tactics did begin to lose their edge starting about the time they met. The Loring family left Massachusetts for Nova Scotia with the British army in 1776, then moved from Halifax to Crown-friendly New York. Joshua Loring, Jr., died in Englefield, England in 1789, leaving behind Elizabeth and five children. She received a Loyalist pension from the Crown until her death in 1831.

When British soldiers evacuated Boston in early 1776, hundreds of Massachusetts Loyalists fled to Nova Scotia or New Brunswick. Because the first United States census did not occur until 1790, the percentage of the Massachusetts population that fled is not possible to gauge accurately. But, assuming that, by war’s end, 80,000 to 100,000 Loyalists from all the colonies had fled, and working from a modern Census Bureau estimate of the total 1776 population of all 13 colonies, roughly four percent of the population in the American colonies left for Canada, East Florida (then in English hands), Bermuda, Jamaica, and, of course, England during the war.

Several thousand enslaved Blacks, freed because they had pledged allegiance to the Crown, fled to Canada. Of those, about 2,000, unhappy with their treatment there, sailed from Nova Scotia in 1792 and helped found the nation of Sierra Leone.

With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 that ended the war, Loyalists who had remained in the states, as well as those who had relocated, found themselves strangers in strange lands. Many wishing to reclaim their homes faced vindictive treatment. Writing to her husband, John, who was in Paris, Abigail Adams reported that “the Spirit which rises here against the return of the Refugees is violent, you can hardly form an Idea of it.” One Tory wrote, “The Rebels breathe the most rancorous and malignant Spirit Everywhere. Committees and Associations are formed in every Colony and Resolves passed that no Refugees shall return nor have their Estates restored. In short, the Mob now reigns as fully and uncontrolled as in the Beginning of our Troubles . . . .”

But return to Massachusetts some did, even several among the 308 individuals named in the 1778 Massachusetts Banishment Act. Many returnees were scrutinized intensively for their fitness to reenter America by locally appointed committees or by the courts. The results varied. Prominent Salem physician and educator Dr. Edward Augustus Holyoke, son of the ninth Harvard president, was deemed to be “a moderate tory, not a high-flying Jacobite. After his return, he embraced the Patriot cause. Another Tory returning to Hampshire County, farther west, was jailed after informing the local Committee of Correspondence that was examining him that “he was in tongue a whig; -- in heart a tory,” and that his ass was a committee of correspondence.”

In Essex County’s Marblehead, Loyalist merchant Thomas Robie and his family had been subjected to “many irritating and insulting remarks” as they left for refuge in Nova Scotia. Upon departing, his wife was heard to retort, “I hope that I shall live to return, find this wicked rebellion crushed and see the streets of Marblehead so deep in rebel blood that a long boat might be rowed through them.” When they sailed back to Marblehead to return home in 1783, a hostile crowd gathered to meet their ship.

During the night, however, a “party of gentlemen went on board of the schooner and removed them to a place of safety” in a distant part of town. Urgent appeals were made “to the magnanimity of the turbulent populace, and the excitement subsided.” Merchant Robie was offered forgiveness in exchange for his family’s establishing an inexpensive dry goods store in town. “Mr. Robie went into business again in a limited extent, and died at Salem about 1812, well esteemed and respected,” a Loyalist chronicler wrote.

In contrast, John Temple, a former commissioner of customs for the Crown in Boston, found himself a shuttlecock in a power struggle between his father-in-law, the wealthy merchant and philanthropist James Bowdoin, who in 1779 unsuccessfully ran for governor against John Hancock. The turbulence caused Temple to give up and return to England.

The Treaty of Paris ending the War for American Independence recommended that the states restore all property and rights taken from Loyalists, and the Continental Congress urged all states to comply. This caused an uproar in Massachusetts. The March 10, 1783 Boston Gazette reported that the first returning Loyalist was run out of town “with a handspike under his crotch, and a halter around his neck.” Boston organized a Committee of Correspondence to cooperate with similar committees in other towns to prevent refugees from returning. Twelve Marshfield Loyalists who had left with the British evacuation were promptly arrested by local authorities on their return to Marshfield and then thrown into the Plymouth jail for four months.

Harsher still, Samuel Stearns, an almanac publisher from Paxton, was arrested within a day of his arrival back home in 1784 and kept in jail for three years. Even more extreme, upon returning home to his wife and ten children in Boston, distiller John Amory was interrogated by representatives of both the Boston Committee of Correspondence and the House of Representatives. Failing to renounce the King, he was deported to Rhode Island and told not to return or he’d be executed.

Since, however, the Massachusetts Banishment Act—enacted by the Massachusetts legislature in 1778—authorized the banishment of returning Tories without a trial by jury, it was, in essence, a bill of attainder. Such actions were forbidden by both the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1778, and the Massachusetts Constitution, ratified in 1780. Moreover, the need to achieve a favorable commercial treaty with England and to encourage the evacuation of British forts in the west argued for repealing or ignoring acts that did not promote amity and amnesty. In April 1787, the Massachusetts legislature, with no dissenters, passed a law offering a general amnesty and repealing selective assessments of returning exiles’ suitability to return.

Over the next three years, the legislature granted citizenship to nine returned Tories and decided favorably on several petitions concerning confiscated estates. As David E. Maas wrote of the Loyalists: “The state soon resumed its earlier policy of humane and selective admission as public vehemence and bitterness quickly subsided. . . . Despite all the warnings of the prophets of doom that the readmission of Tories would end republicanism in America, Massachusetts successfully welcomed its prodigal sons back home.”

Public opinion also became increasingly tolerant of returning Tories as the 1780s wore on. It helped that prominent citizens such as John Adams and Congressional Representative Theodore Sedgewick believed that prosperous, well-educated Loyalist returnees would benefit the state’s economy, so they encouraged and welcomed most of them. Others less prominent recognized that returnees with needed skills or capital would help restore the economic, political, and social fabric, so ordinary citizens, too, eventually welcomed back the retuning Loyalists. It’s fair to say that, by 1789, amity generally prevailed in the new republic.