At a curious stone tower in Somerville, Massachusetts, panic in 1774 could have sparked a war seven months before Lexington and Concord entered the history books.

-

Summer 2024

Volume69Issue3

There are dozens of places you could begin a time-traveling journey through the Revolutionary War. I chose a 300-year-old stone tower in Somerville, Massachusetts that looks like a giant bullet. Why? Because what happened there on September 1, 1774 could have sparked the war seven months early and kept the towns of Lexington and Concord out of the history books.

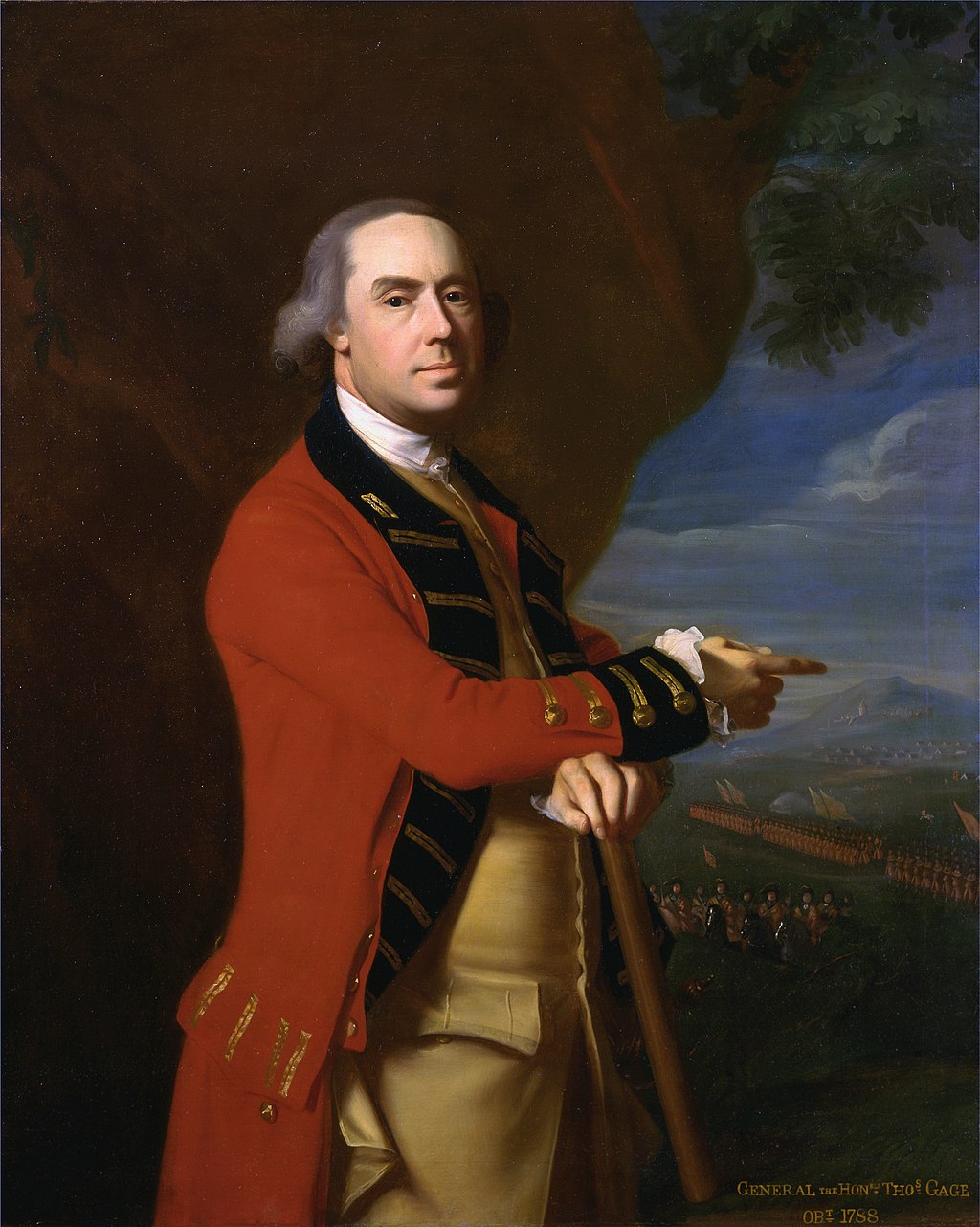

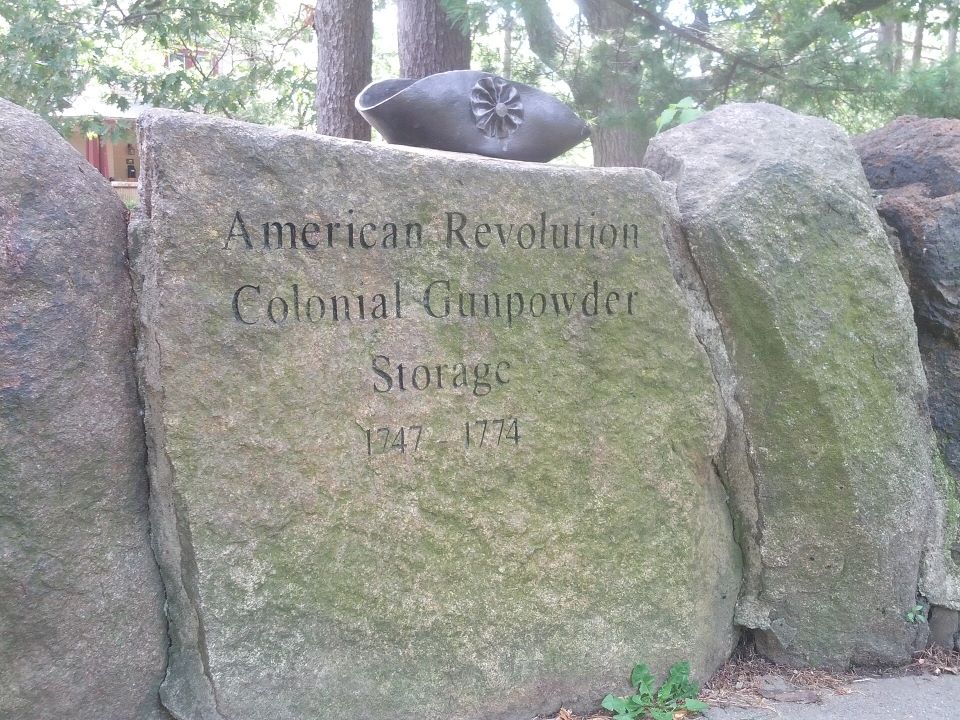

The Powder House rose 30 feet above a small hilltop in Nathan Tufts Park, which is across a nasty traffic circle from the Tufts University campus. “Dogs Must Be Leashed at All Times,” a park sign warned, but, true to their revolutionary heritage, most dog walkers ignored it. A street-level marker told passersby that the tower was built as a windmill around 1703, repurposed as a storage space for gunpowder, and “rifled by General Gage of the colony’s powder on 1 September 1774”—which was fine, as far as it went, assuming that people knew that Thomas Gage was then the military governor of Massachusetts and that gunpowder was a scarce commodity at the time. But it said nothing about the story I had come to pursue, which was about what resulted from Gage’s powder-rifling venture.

Back up the hill I went to look harder.

Only then, gazing at the Stars and Stripes waving from the Powder House’s conical top, did I notice an ancient metal marker—high off the ground and so close in color to the surrounding stone that it blended in—which added some tantalizing detail. Gage had seized 250 half-barrels of powder, it said, and “thereby provoked the great assembly of the following day on Cambridge Common, the first occasion on which our patriotic forefathers met in arms to oppose the tyranny of King George III.”

Tantalizing, but inadequate!

Which patriotic forefathers would we be talking about here? Met in arms? What exactly happened in Cambridge on September 2, 1774?

If I wanted to understand the incendiary confrontation soon to be known as the Powder Alarm, I figured, it was time to take a Cambridge walk with a man who lives the Revolution every day.

The first thing one notices about the proprietor of Boston 1775—a blog with the tagline: “History, analysis, and unabashed gossip about the start of the American Revolution in Massachusetts”—is the pair of 19th-century-style sideburns that threaten to rendezvous under his chin. Otherwise, he looks like a well-groomed graduate student: jeans; blue-and-white-checked shirt; thick, dark hair; and a youthful face that made me surprised to hear that he was 49 when I met him. He writes as “J. L. Bell,” the world being overstocked with John Bells, yet it would be hard to mistake the eclectic erudition of Boston 1775 for the work of anyone else.

How does a longtime book editor evolve into an everyday revolutionary blogger? Over a sandwich a few blocks west of Harvard Square, Bell told me the story of the 11-year-old cause of it all.

He had started to think about writing a historical novel for kids, when he ran across a reference to a boy who had been shot and killed a week and a half before the Boston Massacre. “It’s very unusual to find events in history where children are agents and their decisions actually matter,” Bell said, but in 1770, “the boys of Boston were doing their own picket lines” as part of a boycott of British goods. One day, some boys got into an altercation with a boycott opponent and began chucking rocks through his windows. The man fired into the crowd and the rest was history—more than a thousand people showed up for young Christopher Seider’s funeral—except that Bell didn’t know that history. Growing up in Revolution-proud Massachusetts, he had assumed that all the important stories had been thoroughly explored. He was wrong.

Intrigued, he did some serious digging. After a while, he noticed that the internet was revolutionizing how history could be researched and written. Should he be thinking about a blog? he wondered. “Just do it,” a friend urged.

Ten years and 3,624 posts later, Boston 1775 had credentialed John Bell to an extent that few would have predicted. Academics consulted him; lecture opportunities found him; the National Park Service hired him to write a book-length report on George Washington’s Cambridge headquarters; and random history-minded journalists began pestering him for help. When I got in touch, he was deep into finishing The Road to Concord, a book that devotes its first two chapters to the events of September 1 and 2, 1774.

After lunch, we set out on our Powder Alarm walk. First stop: a yellow colonial at 42 Brattle Street, between the Brattle Theatre and an Ann Taylor store.

Today, 42 Brattle houses the Cambridge Center for Adult Education. In 1774, as tensions between Great Britain and New England neared an all-time high, it was home to William Brattle, a 68-year-old gentleman farmer and Massachusetts militia general who had kicked off the September craziness by writing the governor a letter. Composed in late August, it informed Gage, who was his boss, that gunpowder was starting to disappear from the Powder House. Gage took the hint. Before dawn on September 1, longboats ferried some 250 Boston-based British soldiers three miles up the Mystic River, where they got out and marched another mile to their destination. Removing hobnailed boots, lest a spark blow them to kingdom come, they collected the remaining powder in the tower; a few went to Cambridge to confiscate a couple of artillery pieces, as well. All were safely back in Boston by noon, and the governor was a happy man.

Not for long, though.

Later that day, Gage’s enemies somehow got their hands on Brattle’s letter. A crowd of local protesters showed up outside his house, but, by then, the owner was gone. “He went into Boston,” Bell said, “and never saw Cambridge again.” Unsatisfied, the crowd reassembled half a mile up the street, at the home of a colonial official named Jonathan Sewall, whose wife said he wasn’t home. The protesters didn’t believe her and tried to break in. Someone inside fired a pistol—accidentally, it was claimed—which sobered everybody up, and the crowd dispersed.

As Bell and I walked up to Sewall’s house (now 149 Brattle), I asked what the tony 21st-century neighborhood had been like in 1774. For one thing, he said, it was far less crowded: Just seven elegant residences, widely spaced, sat along a mile-long stretch of what was then called the Watertown Road. They were “estates with farms, not townhouses; this was out in the country.” Enslaved people did the farming, and many families on Tory Row—“a name that came along later”—had fortunes based on Caribbean sugar plantations. All of which made these folks very different from the several thousand farmers and tradesmen who materialized on Cambridge Common, just a few blocks away, on the morning after the September 1 disturbances.

To understand what those men were doing there, we need to back up a bit.

When I first had the idea for a traveling revolutionary history, tracing the events of the war itself seemed plenty challenging enough, and I decided to skip sites related to causes of the Revolution. I knew about taxation without representation, of course, and had a pre-Lexington timeline in my head that included the French and Indian War, the Stamp Act, the Boston Massacre, and the destruction of British tea by angry guys wearing face paint. But, now that the Powder Alarm was on my radar screen, I needed a refresher course on the Massachusetts Government Act—which I had entirely forgotten, until Bell reminded me that it was crucial.

Briefly: When news of the Boston Tea Party reached England, early in 1774, the British government went ballistic. It closed the port of Boston, ordered redcoats into the center of town, and, somewhat less famously, set out to eliminate local self-government in Massachusetts.

Before this, Bell said, there had been “a balance of top-down and bottom-up power” in which the top, in London, “appointed the governor, who appointed the sheriffs and judges,” while the bottom, “which was really the middle, the property-owning white males,” elected legislators, town officials, and local militia officers. Now, however, members of the legislature’s upper house, known as governor’s councilors, would be appointed directly by the Crown. Judges and other court officials, formerly under the indirect control of citizens, would serve exclusively at the governor’s pleasure. Town meetings would be limited to one per year, unless the governor gave special permission.

Resistance began the minute that news of the Government Act crossed the Atlantic. Within weeks, royal authority outside Boston had almost disappeared.

“Huge crowds showed up in court sessions in western counties, where there were no British troops. They often showed up in their militia units, not armed, but with a clear implication of, you know, there are thousands of us and fourteen of you.” The crowds demanded that courts stop doing business under the Government Act and that all the “new-fangled” governor’s councilors resign. By the time Brattle wrote his letter, Gage knew he was in trouble. Without reinforcements, he didn’t have enough men to put down what historian Ray Raphael calls “the first American Revolution.” The best the governor could do was go after the insurgents’ military supplies.

So, that was what he did.

But the unintended consequences of the Powder House raid kept getting worse.

News of the raid spread through the countryside that night, accompanied by alarming rumors: Gage’s troops had shot and killed people! The British Navy was bombarding Boston! The town was burning! The rumors didn’t all make sense (why burn a town where your own men are quartered?), but there was no time to confirm them, and by now, the country people were used to acting forcefully on their own. “Each individual community got together and decided: ‘Now, we march,’ ” Bell told me. A traveling merchant, in one of the few detailed accounts that survive, described repeated scenes of purposeful chaos: “at every house, Women & Children making Cartridges, running Bullets, making Wallets, baking Biscuit, crying & bemoaning & at the same time animating their Husbands & Sons to fight for their Liberties, tho’ not knowing whether they should ever see them again.”

By early morning on September 2, thousands of men with muskets filled the roads to Cambridge.

Somewhere, the truth caught up with them: No one had been killed; Boston wasn’t burning. They parked their guns outside of town and proceeded to the Common “armed only with sticks,” one newspaper reported, but still with business to conduct. As long as they were here, why not demand resignations and apologies from the Cambridge men who had taken office under the Government Act? This was what they were doing, peacefully enough, when six anxious resistance leaders from Boston showed up. These gentlemen, Bell said—and they were gentlemen, with the best-known being Dr. Joseph Warren—were “worried about the farmers attacking somebody” and discrediting a movement whose chief hope, still, was that London would back down.

The Bostonians tried to take charge. For a while, they appeared to succeed. Then—boom!—someone recognized a customs commissioner named Benjamin Hallowell, who happened to be passing through Cambridge in his chaise. It was as though a grenade had been tossed into the gathering: More than a hundred men mounted up to pursue Hallowell toward Boston. Many of the riders got talked out of it, but some didn’t, and the chase continued. Others in the crowd went back to retrieve their muskets. Before long, Thomas Oliver, the lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, heard a knock on his Tory Row door.

Set back from the street, surrounded by outbuildings and lush green space, Oliver’s mansion—now occupied by the president of Harvard— helped me imagine the 1774 neighborhood better than any other stop on Bell’s tour. Less easy to picture, however, was the angry crowd that had materialized outside it for the final act of The Day the War Could Have Begun.

Lieutenant Governor Oliver, like those six nervous gentlemen from Boston, had spent much of September 2 trying to keep the peace. That morning, a delegation from the militiamen had asked him to travel to Boston and urge General Gage not to attack them; Oliver complied, returning to report that Gage had no plans to send troops. After declining a relatively polite request that he resign—besides being lieutenant governor, Oliver served on the governor’s council—he seized the opportunity of the Hallowell furor to head home. But the mood on the Common had changed, Bell said, and “the crowd decided that they weren’t going to let anybody in Cambridge remain on the council.” This meant walking a mile west to confront Oliver en masse.

Inside his house, the governor—presented with a resignation document to sign—once again refused.

Outside, thousands of men—a quarter of them armed—got impatient.

“The leaders of the crowd had lost control,” Bell said. Men pressed up to Oliver’s open windows; his wife and children freaked out. Members of the delegation inside “were pleading with him to sign because they didn’t know what these men were going to do.” Finally, he gave in, adding a line of explanation to the prepared text.

“My house at Cambridge being surrounded by about 4000 people, in compliance with their command,” Oliver wrote, “I sign my name.”

The Powder Alarm was over.

Technically, the Revolutionary War had not broken out.

Yet, thanks to the actions of thousands of forgotten men—their names, unlike those of the elite leaders on both sides, do not appear in the historical record—few illusions remained about how soon the shooting might begin.