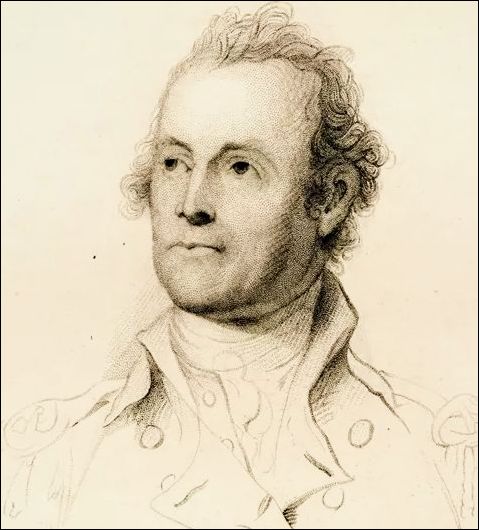

John Glover and the men of Marblehead saved the Continental Army several times, and then helped it cross the Delaware to victory at Trenton and Princeton.

-

Spring 2024

Volume69Issue2

Editor’s Note: The author of 13 books, Patrick K. O’Donnell is one of our leading military historians. His fascinating book about the crucial role that John Glover and the Marblehead men played in the Revolution, The Indispensables: The Diverse Soldier-Mariners Who Shaped the Country, Formed the Navy, and Rowed Washington Across the Delaware, reads like David McCullough’s 1776 and Stephen Ambrose’s Band of Brothers. We are delighted to publish this essay adapted from the book.

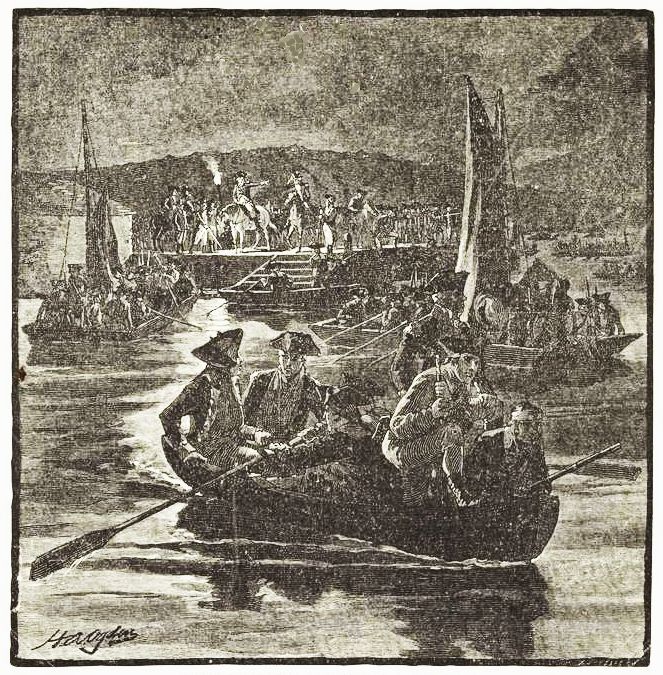

Trailing blood in the snow, the often-shoeless soldiers marched to the boats at night in the midst of the storm as sleet pelted their bodies. At the Delaware’s edge, men from Marblehead packed General George Washington’s army into the vessels. They began crossing the fast-flowing, ice-chunk-filled river – a challenging task for even the most experienced sailors. With the morning rapidly approaching, every moment counted to maintain the element of surprise against the Hessian garrison at Trenton. Despite the odds, Colonel John Glover’s soldier-mariners pressed on.

In the winter of 1776, a pall of gloom and the prospect of capitulation hovered over the nascent United States. The Continental Army had endured one crushing defeat after another. The ragtag fighting force had thinned from over 18,000 strong to a few thousand men. With most enlistments set to expire on December 31, 1776, it would shrink to mere hundreds, who were largely barefoot and starving. As Washington direly confided in a letter to his brother, “I think the game is pretty near up.”

To turn the tide, the commander in chief staked the entire war on a desperate gamble, involving some of the most difficult maneuvers of the Revolutionary War: a night attack, an assault crossing a river in the middle of a nor’easter, and a strike on the British-controlled town of Trenton. The ominous countersign “Victory or Death” marked the gravity of the operation.

In these extreme circumstances, Washington turned to the only group of men he knew had the strength and skill to deliver the army to Trenton – John Glover’s Marblehead Regiment. These indispensable men miraculously transported Washington and the bulk of his army across the Delaware in the heart of the raging storm, without a casualty.

Two sizable portions of the army not guided by the Marbleheaders failed to cross that night. But the courage and nautical talent of the “indispensables” allowed the army and the mariners to play a vital role in the land battle that changed the course of the Revolutionary War. And then, through their own initiative, without orders, the Marbleheaders captured a crucial bridge at Trenton that sealed the fate of the battle as a decisive American victory.

As at the crossing of the Delaware, there were several other times when the American Revolution could have met an early, dramatic demise, had it not been for the SEAL-like operations and extraordinary battlefield achievements of this diverse, unsung group of men and their commander, John Glover. Their ideas and influence shaped the Revolution and a young country. Marbleheaders formed the origins and foundation of the American navy, and captains from the northeastern, coastal Massachusetts town smuggled or seized vital supplies – including gunpowder, an absolute necessity, without which the Revolution would cease to exist.

These “Indispensables,” a motley group of mariners, had pasts checkered by smuggling and privateering. A more diverse collection of individuals than any other unit in the Continental Army, the Marblehead Regiment included free African Americans and Native Americans within its ranks, making it one of America’s first multiethnic units. In fact, its rolls recorded roughly a third as being “dark complexion,” a third not labeled, and another third as “light complexion.”

The Start of Resistance

For John Glover and many of his neighbors, resistance to the British Crown began in March 1770, after they read accounts of what came to be known as the Boston Massacre, an event that roiled the citizens in Marblehead and throughout Massachusetts, and forced open the growing political fissure between the Loyalists and the Whigs.

“So enraged are the people at the late horrid Massacre in Boston, that it is thought, if a proper Signal should be given, not less than Fifteen Hundred Men, from this Town (Salem) and Marblehead, would turn out at a Minute’s Warning, to revenge the murders,” one Salem resident wrote.

Among the Marblehead men was Elbridge Gerry, an outspoken zealot, although he was only 26 at the time. Extensive correspondence between Gerry and the Boston radical Samuel Adams helped spawn the idea of creating committees of correspondence to sway public opinion in response to British atrocities. Gerry would later sign the Declaration of Independence and gain notoriety as a member of Congress for his efforts to “Gerrymander” districts.

In 1774, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress directed towns in the region to organize companies of minutemen, troops who could be ready at a moment’s notice to defend the safety of their neighbors. Each company was to have a minimum of 50 privates and several officers and noncommissioned officers, at least a quarter of whom should be on call at any given time.

Marblehead already had an active militia, and was far more prepared than most of the neighboring towns. According to the Essex Gazette at the time, they drilled “three or four times a week, when Col. Lee, as well as the Clergymen there are not asham’d to appear in the ranks, to be taught the manual exercise, in particular.” The Marbleheaders hired a tutor in military history, while “a fencing master taught them the use of the small and broad sword,” and a former British Army sergeant taught them the finer arts of war.

“The madmen of Marblehead are preparing for an early campaign against his Majesty’s troops,” scoffed a Loyalist newspaper, mocking the idea that Americans could threaten the most experienced and skillful military professionals at the time.

Experienced in smuggling and privateering, the Marblehead mariners played a crucial role throughout the Revolution by supplying cannons and gunpowder to the patriot cause. Weaponry was sourced from foreign countries and snuck through the British blockade. Wives and daughters sewed thousands of cartridges of flannel filled with gunpower.

In January 1775, Marblehead voted to reorganize its militia and assigned John Glover as a lieutenant colonel and second-in-command. The following month, men from the area led by Samuel Trevett snuck aboard the 20-gun British warship MS Lively and liberated guns which the militia desperately needed.

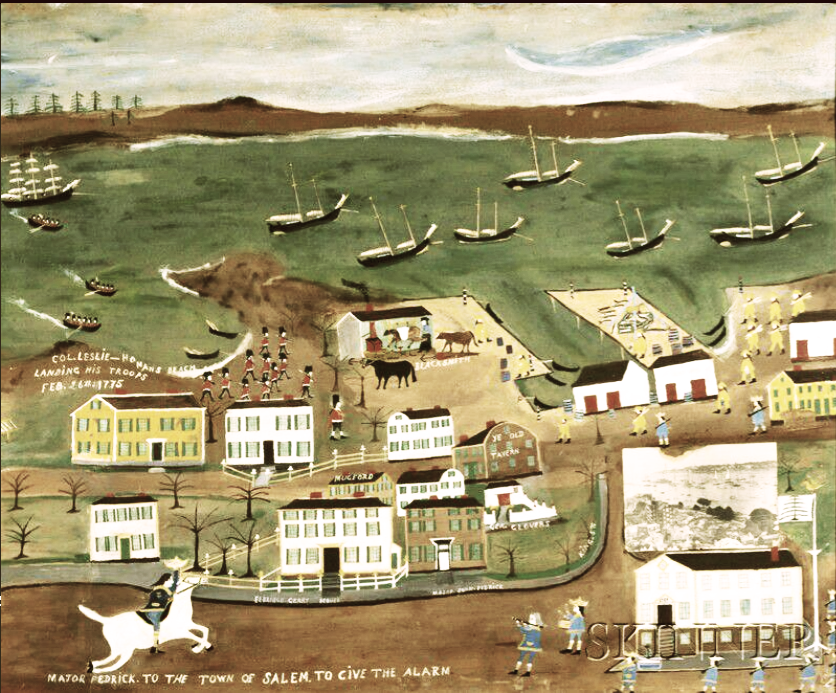

Then, on a wintry Sunday afternoon, armed Marbleheaders met British troops in a dramatic showdown at the North Bridge in Salem and prevented them from seizing cannons that were hidden there.

Shots Fired at Lexington

When word of the shots fired at Concord reached the militia on April 19, many of the men, including John Glover, Caleb Gibbs, and Gabriel Johonot, rushed to Lexington and battled the British on their retreat. Johonot later recalled that, on that day, he volunteered in Captain John Glover’s company and “marched and proceeded from Marblehead to harass the British Troops, on their retreat from Lexington, and from that day, continued in the Revolutionary Army.”

As the British fought their way back to Boston, minutemen and militia swarmed them on all flanks. The Marbleheaders engaged the redcoats in Menotomy (now known as Arlington), fighting house-to-house and hand-to-hand. Many of the local minutemen were defending their homes, firing from windows and floors.

“The British soldiers were so enraged at suffering from the unseen enemy that they proceeded, and put at death all those found in them,” recalled an officer in the Royal Welch Fusilliers. General Hugh Percy saved the day for the British by arriving with reinforcements and directing his compatriots down a side road to Charleston to avoid the main body of Americans.

Glover’s Hannah, the First U.S. Navy ship

By the middle of August 1775, Washington took the revolutionary step of bringing the war to the sea, first, by ordering John Glover to outfit his schooner with four cannon. The 78-ton Hannah, likely named after Glover’s wife, had fished for ten years on the Grand Banks and traded in the West Indies.

The commander in chief originally scotched the idea of armed ships, but the quest for gunpowder proved instrumental in softening his position. Since John Glover had a ship for rent, for 78 dollars a month, she became “The first Armd Vessell fitted out in the Service of the United States,” as Glover later explained.

An armed ship could be viewed as major escalation in the Revolution. Sovereign and independent nation-states had their own flagged ships. Ultimately, an armed vessel crewed by the Continental Army could also export the ideas and ideals of the Revolution to other nations in a way that a merchant vessel could not. While Hannah had a career of only a couple of months before being damaged by the 16-gun HMS Nautilus, she is considered the beginning of the American Navy.

Marblehead ships also answered the call by smuggling crucial powder and supplies, and running the gauntlet of the British ships blockading American ports. They transported 69,000 pounds of gunpowder from the Caribbean alone. From trading partners in Bilbao, Spain, they brought scores of cannon, tons of powder, thousands of muskets, and military supplies. Washington and Glover created the process for buying, fitting out, arming, and crewing vessels, the protocols for signals, and prize courts for dealing with captures.

Once again, the efforts of the Marbleheaders proved indispensable.

The Dramatic Escape from Long Island

After withdrawing from Boston, the British General Howe waited for reinforcements in Halifax and trained his troops in light infantry tactics to adapt to the American style of fighting, while Washington moved his army south to defend New York.

On June 29, 1776, New Yorkers witnessed a jarring sight: New York Harbor appeared to resemble “a wood of pine tree trimmed.” Hundreds of ships with their naked masts had dropped sail and anchored as over half of the mighty Royal Navy surrounded the city. “All London was afloat,” claimed one of Washington’s soldiers.

The British invasion force had arrived. Over the next six weeks, 23,000 British regulars and 10,000 of their Hessian allies descended on American shores via New York’s harbors, carried by more than 500 transports and 70 British warships.

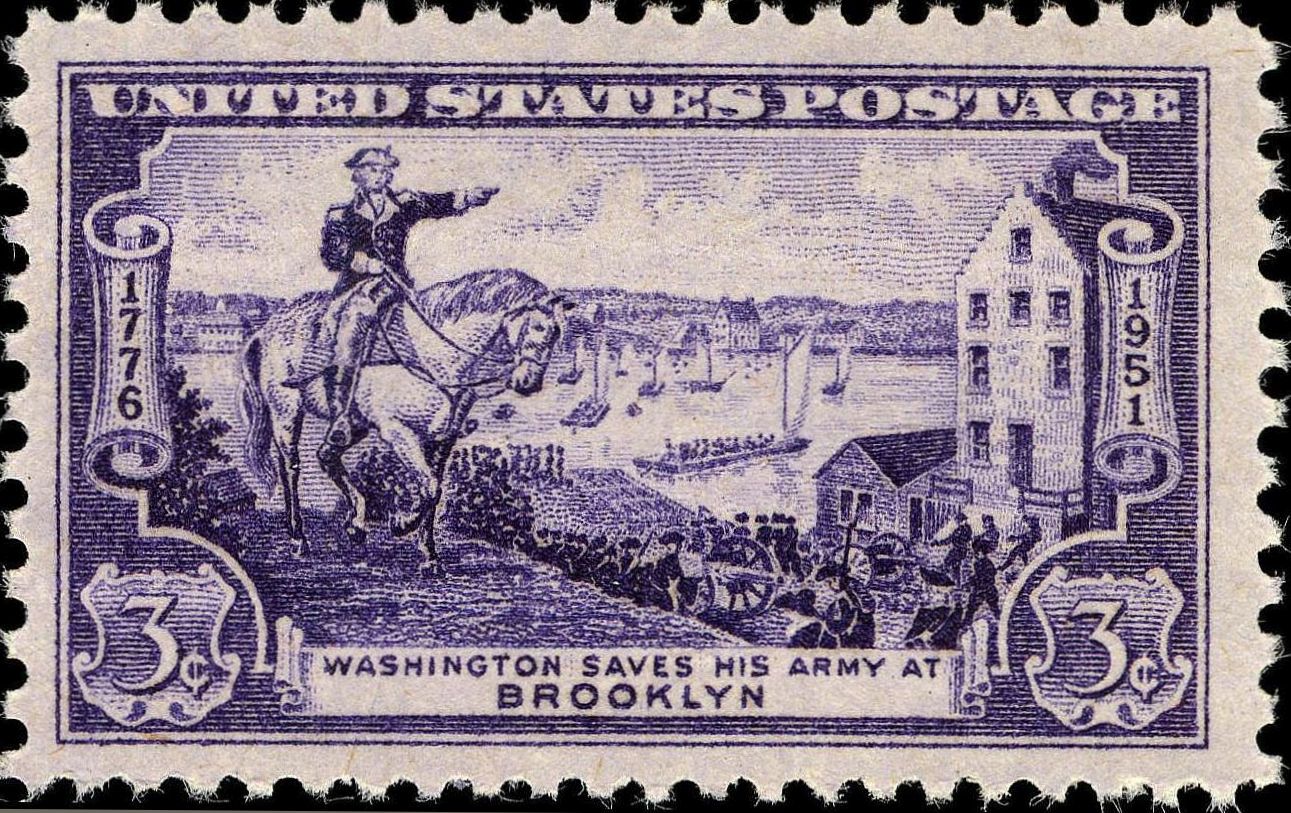

Two months later, the Continental Army faced annihilation after losing the Battle of Brooklyn. The much-larger British army had inflicted over 2,000 casualties and trapped George Washington’s men against the East River. The fate of the army – in fact, the fate of the Revolution itself – now lay on the shoulders of the fishermen and sailors of the Marblehead Regiment who were asked to ferry the entire Continental Army across the East River in small boats.

On the stormy night of August 29, 1776, Washington knew that escaping from Long Island would be treacherous. Major Benjamin Tallmadge observed, “To move so large a body of troops, with all their necessary appendages, across a river a full mile wide, with a rapid current in the face of a victorious, well-disciplined army, nearly three times as numerous as his own, and a fleet capable of stopping the navigation, so that not one boat could have passed over, seemed to present most formidable obstacles.”

The Americans were not only surrounded by thousands of British and Hessian troops, but, to get across the river, they faced three potent natural enemies: time, wind, and tide. It was the middle of summer; therefore, the night would be short. The Marbleheaders faced the task of transporting Washington’s men and materiel, without lights and under the cover of darkness, to screen their movement from watchful eyes.

Amphibious operations and disengagement under pressure are some of the most complex and dangerous moves in warfare. Even with a rearguard, the Americans rendered themselves vulnerable as they departed their defenses and boarded the boats. A British night attack might prove unstoppable.

“Colonel Glover, who belonged to Marblehead, was called upon with the whole of his regiment fit for duty, to take the command of the vessels and flat-bottomed boats,” wrote contemporary historian William Gordon. “Most of the men were formerly employed in the fishery, and so, were peculiarly well qualified for the service.”

The Marbleheaders had worked together as a team for over a year. Many had also served together in the Grand Banks. These men, their leadership, their grit, and their experience sailing some of the most treacherous waters in the world would be essential in accomplishing the near-impossible that night.

“The colonel (Glover) went over . . . to give directions; and about 7:00 at night, officers and men went to work with a spirit and resolution peculiar to that corps.” The first boats manned by the Marbleheaders to make the crossing did not carry troops. Instead, Brigadier General Alexander McDougall, a former merchant mariner who was in charge of the evacuation,

ordered the horses, ammunition, cannons, and baggage transferred to the other side of the river.

As the heavy rains, which had fallen two days and nights with little intermission, continued, the Americans spiked the largest guns – which were too heavy to move and would have sunk in the oozing, brown mud on the shore if the men had tried to load them into the boats.

The entire Continental army made it across the East River, and eventually worked their way north on Manhattan island to avoid capture by the much-larger British forces.

A Courageous Stand at Pell’s Point

As dawn broke on October 18, John Glover climbed a small rise on the coast of Pelham Manor, New York, north of Manhattan. Upon reaching the summit, he lifted his spyglass to his eye to scan the horizon; what he saw exceeded his worst nightmares. By his own account, he “discovered a number of ships in the Sound underway; in a short time, saw the boats, upwards of two hundred sail, all manned and formed in four grand divisions.”

British forces totaling about 4,000 men were landing at Pell’s Point, a peninsula on Long Island Sound, in a move to outflank and trap Washington and his army to the south. Glover immediately sent a message to General Charles Lee, reporting the ships he had seen. Then, without waiting for orders, he formed up his brigade of about 750 men to march toward the point and oppose the much larger force advancing north.

By the time Glover arrived, the British had marched a mile and a half inland and seized the high ground. “The enemy had the advantage of us,” Glover wrote, “being posted on an eminence which commanded the ground we had to march over.”

Glover later recounted, “Oh! the anxiety of mind I was then in for the fate of the day, the lives of seven hundred and fifty men immediately at hazard, and under God, their preservation entirely depended on their being well disposed of; besides this, my country, my honour, my own life, and everything that was dear, appeared at that critical moment to be at stake.”

Despite his anxiety, Glover hatched an ingenious battle plan. Some fences interspersed with boulders and rocky outcroppings lined Split Rock Road, which would force the roughly 4000 enemy soldiers, three-quarters of them battle-hardened Hessian allies, to stick to the roadway and advance in a column.

Today, a portion of the battlefield runs through the early holes of the Split Rock Golf Course. You can still see the remains of the stone fences and the rocks on the course. By placing his men behind the stone fences, Glover set up a defense to inflict as many casualties as possible, despite being outnumbered approximately five to one.

The American advance guard approached within 50 yards of the enemy. They exchanged five rounds with the Redcoats and Hessians and then fell back on Glover’s orders, having inflicted four casualties.

Believing that they had the Americans on the run, the British “gave a shout and advanced.” When the Redcoats were within 30 yards, the Americans suddenly rose up as one, rested their weapons on the stout wall, and fired on the enemy with their motley assortment of muskets.

With the enemy so near, and with the fence providing a convenient resting place for their weapons, many of the American bullets found their mark, and dozens of Redcoats and Hessians dropped. At the vanguard of the British attack, the Americans faced the elite light infantry. In the thick haze of smoke, they expected an order for a bayonet charge, but none came.

Eventually, the enemy’s overwhelming numbers forced Glover’s men to retreat. But the English commander-in-chief, William Howe declined to pursue the Americans, who had done so much damage to his forces. The total number of British casualties is unknown, but they must have been substantial because Howe grossly overestimated the number of Continentals he had faced, believing them to be over ten times their actual number. In hindsight, it is easy to understand how Howe and Major-General Henry Clinton could have estimated so poorly.

For more information, see in this issue “Home of

John Glover Threatened with Demolition,” by Nancy Schultz

One historian noted, “It is difficult to believe that 400 Americans, familiar with the use of firearms, sheltered by ample defenses from which they could fire deliberately, and with their guns rested on the tops, could have fired volley after volley into a large body of men, massed in a compacted column in a narrow roadway, without inflicting as extended damage as this.”

Far more critical than the casualties they inflicted was the strategic advantage and time that Glover’s men bought for Washington. While the Massachusetts men held off the enemy, Washington began moving the bulk of his forces north toward White Plains. Some historians have noted that Howe might have been able to stop the retreating Americans if he had pressed forward after the battle at Pell’s Point. However, his fear of Glover’s men kept him in place while the Americans escaped once again.

Desperate Gamble at Trenton

By December 1776, comfortably ensconced in his opulent New York headquarters, William Howe was feeling far more confident than George Washington and his beleaguered army. Following the string of victories in New York, Rhode Island, and New Jersey, Howe had every reason to think that the war would soon be over, with the rebellious American colonies restored to their rightful place in the British Empire. He believed it was only a matter of time before the patriots’ political will collapsed.

Eighteenth-century armies, in accord with the European style of warfare, generally did not fight during the coldest months. Supplying an army during the winter was extremely challenging. The preferred method of moving supplies, by water, could be hampered by ice. Ground transportation was at the mercy of mud-clogged or snow-covered roads. An army, dependent upon horses and oxen to move its supplies, required sufficient forage, which was scarce during the winter. Typically, troops rested and waited for spring to resume their campaigning.

With Washington’s army on the ropes, Henry Clinton advised “relentless chase.” But Howe overruled him. Clinton had warned of the vulnerability of Trenton and other outposts. But Howe dismissed his concerns.

Washington hoped to attack the Hessian troops in Trenton quickly, before they could call in reinforcements from Princeton or Bordentown. To that end, the commander-in-chief planned for the Continental Army to surround the town and envelop the soldiers billeted there. He would lead the main body of the troops across the Delaware River at McConkey’s Ferry, nine miles north of Trenton. Washington’s force, including the Marblehead Regiment, would then march south, separating into two divisions along the way, and allowing them to approach the town from two directions.

“You need not be troubled about that, General; my boys can handle that,” John Glover laconically assured Washington. Considering all the variables and complexities involved in transporting thousands of soldiers and their cannon across the Delaware to attack Trenton, the commander-in-chief had asked Glover whether it was even imaginable that the plan would succeed.

Assured by Glover, Washington and Henry Knox were relying on the Marblehead Regiment to do something even more challenging than their previous feats: cross a nearly 1000-foot-wide, ice-choked river at night and, unbeknownst to them at the time of the planning, during a raging nor’easter. Very few men in the army could swim, and drowning – not to mention frostbite and hypothermia – posed a deadly threat for anyone who went overboard.

Facing a task this daunting, most experienced sailors would recommend postponing the operation until the weather conditions were more favorable. But, based on the Marbleheaders’ experience in forging a navy, their miraculous evacuation of the army across the East River, and the delaying action at Pell’s Point, John Glover had complete confidence in his men.

“The noise of the soldiers coming over and clearing away the ice, the rattling of the cannon wheels on the frozen ground, and the cheerfulness of my fellow-comrades encouraged me beyond expression,” recalled John Greenwood, the Massachusetts fifer, mariner, and future dentist of George Washington.

But, once across the river, the men had to march nine miles in the dark toward Trenton. “During the whole night, it alternately hailed, rained, snowed, and blew tremendously,” recalled Greenwood. The men’s suffering was acute. Marblehead lieutenant Joshua Orne became so numb that he passed out on the side of the road and was nearly covered with snow. Someone in the rear of the regiment rescued him.

As the Americans began attacking the Hessians, Glover realized that there was a critical bridge at the south end of Trenton which could afford the enemy a means of escape. Without orders, he directed his men to attack the guards on the bridge, scattering them, and then crossed the Assunpink Creek and took up positions on the crucial high ground on the south bank.

The Americans captured the bulk of the Hessian garrison, dramatically turning around America’s fortunes in the war. Glover’s men had not only transported the army across the river; they sealed the fate of the Trenton garrison by closing their main egress of escape.

Returning Home to “Naught but Cheat”

On the cold, snowy evening of January 20, 1777, the tattered remains of the regiment limped back into Marblehead, Massachusetts after the victories at Trenton and Princeton. Many were very sick or wounded. The men had marched for weeks, traversing more than 300 miles on the journey in brutal weather. With their muscles spent and their bones weary, only willpower propelled them forward the final steps home.

But, upon arriving home, they found a festering economic disaster, instead of a joyous homecoming. With Marblehead’s fishing industry shuttered while most of its inhabitants fought in the war, those left behind were starving. One resident, Molly Guttridge explained, “We cannot now get meat nor bread; we see the world is naught but cheat.... Some say they an’t victuals nor drink. Others say they are ready to sink.”

Exhausted physically, mentally, and monetarily from years of conflict, the citizen-soldiers had no reserves left on which to draw. John Glover, physically drained, infirm, nearly ruined financially, and with his wife sick, decided to part ways with the army.

He considered the absence permanent, but, in February 1777, Congress promoted him to brigadier general. He initially declined the commission, writing to George Washington on April 1, 1777, “I Cannot think myself in any Degree Capable of doing the duty, necessary to be done, by an officer of that Rank.”

General Washington responded by conveying an understanding of Glover’s situation and then praising the Marbleheader: “After the conversations I had with you, before you left the army, last Winter, I was not a little surprised at the contents of yours of the first instant. I know of no man better qualified than you to conduct a Brigade. You have activity and industry, and, as you very well know the duty of a colonel, you know how to exact that duty from others.”

A master motivator, Washington then laid on the guilt:

Glover Returns to Face General Burgoyne in Saratoga

John Glover relented and returned to the service. In short order, he found himself, once again, in command of a brigade of New Englanders who would serve decisively in the Revolution.

In the summer of 1777, Glover and his new unit moved north once again. Assigned to the army commanded by General Horatio Gates, they would soon face off against British forces commanded by General John Burgoyne, who had invaded New York from Canada. Throughout September and October, the two armies fought a series of pitched battles, now known collectively as the Battles of Saratoga.

While Glover and his men frequently distinguished themselves, they suffered casualties. On September 19, at Freeman’s Farm, his men fought nonstop for more than six hours in the heaviest combat. As he explained, “both armies seemed determined to conquer or die. One continual blaze, without intermission till dark.... during which time we several times drove them, took the ground, passing over great numbers of their dead and wounded. We took one field piece ... and obliged to give up the prize. They were bold, intrepid and fought like heroes, and I do assure you, Sirs, our men were equally bold and courageous & fought like men.” Just weeks later, the armies faced off again.

On October 7, a portion of Glover’s Brigade, under the command of Benedict Arnold, launched a furious counterattack on the British. This time, the outcome was more decisive. Glover’s men and those with them forced Burgoyne to retreat north toward Canada.

Eventually, the British were forced to surrender an army of over 6,000 soldiers, and the battles in the Saratoga area were the great turning point in the Revolution.

Glover “Broken & Shatter’d to Pieces”

By the summer of 1782, John Glover had had enough of the war. “When I enter’d the service in 1775, I had as good a Constitution as any Man of my Age,” he wrote Washington, “but it’s now broken & shatter’d to pieces, good for nothing, & quite worn out; However, I shall make the best of it.”

Outfitting Washington’s navy and his men had ruined Glover financially: “The expense of my little fortune, earned by hard labor and industry; to sacrifice ...and total ruin of a family of young children.” Able to eke out only two hours of sleep every night, Glover likely suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. “So far as my State of health will permit; which at present, is Very much impaired, and exceedingly precarious, (God, alone, knows how long it may Continue So) as my want of Sleep, night Sweats ...”

John Glover officially retired from the Continental Army that July, having succeeded at all the tasks Washington assigned him, but at a nearly unbearable personal cost.

Excerpted from The Indispensables © 2021 by Patrick K. O’Donnell. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.