The president worried that his grandson had “an unconquerable indolence of temper, and a dereliction, in fact, to all study.”

-

September 2023

Volume68Issue6

Editor's Note: Charles S. Clark is the author of George Washington Parke Custis: A Rarefied Life in America’s First Family, which was published in 2021 by McFarland Books. A retired D.C. journalist, he writes frequently about his hometown of Arlington, Virginia.

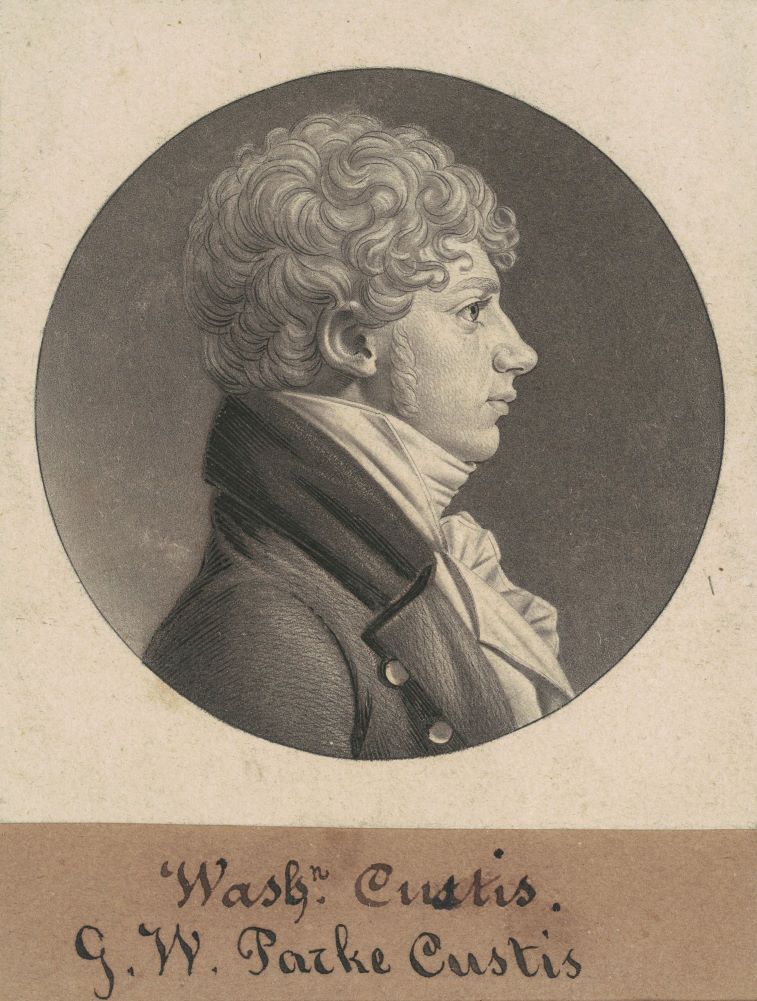

Although George Washington didn’t father any children of his own, he devoted years to caring for two privileged step-children and two step-grandchildren. Most accomplished of those elite offspring was George Washington Parke Custis (1781-1857), whom Washington, with his wife Martha, adopted as an infant and raised in the rarefied atmosphere at Mount Vernon.

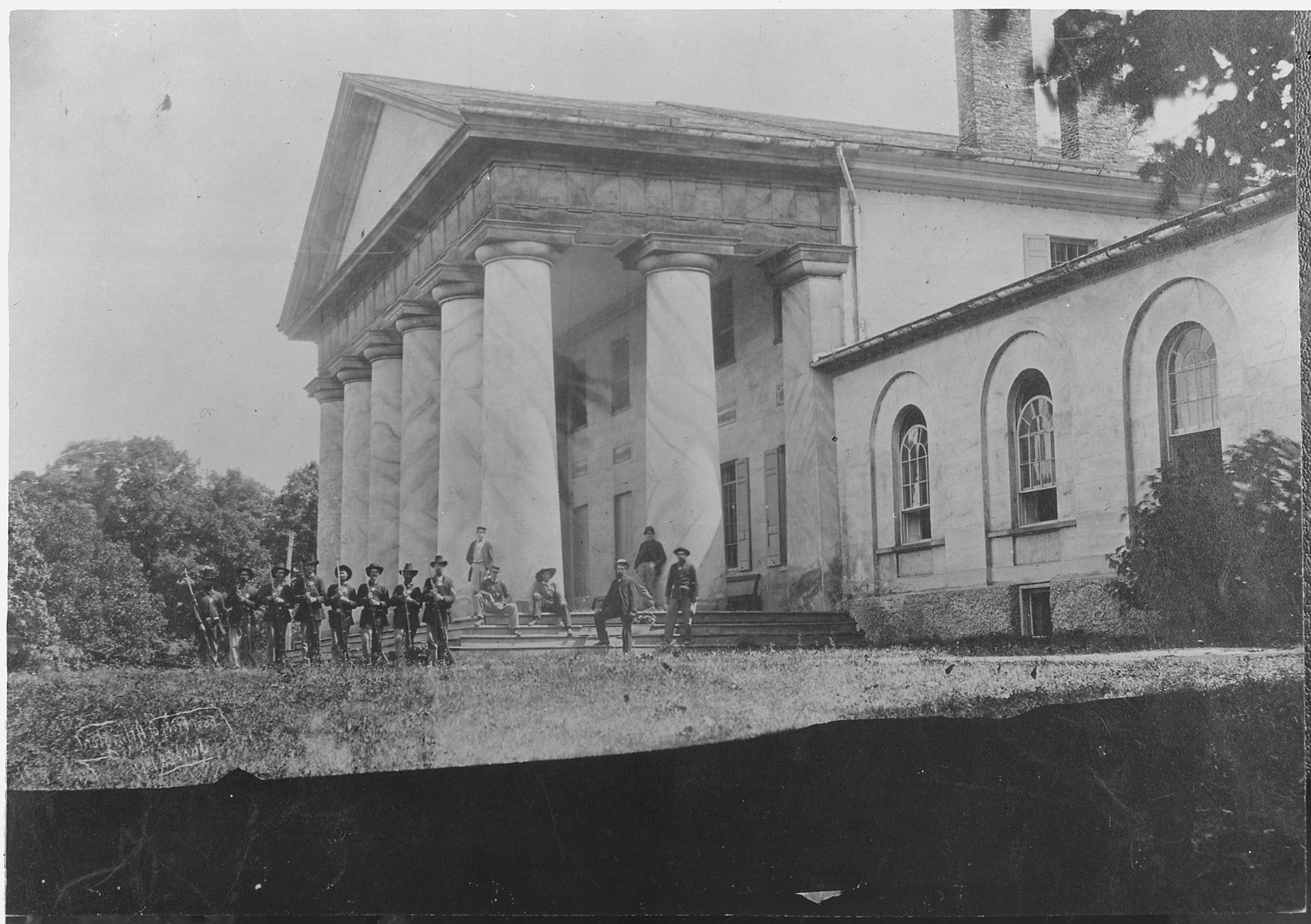

The young Custis would become known for building, with enslaved labor, Arlington House on the Potomac River, his life-long commemorations of Washington’s memory, his patriotic oratory, and marrying his daughter Mary to a promising Virginia soldier named Robert E. Lee.

But those adult accomplishments were hardly preordained. “Washy” or “Wash,” as intimates called him when he was a youngster, enjoyed being served by an enslaved work force, sitting for portraits by prestigious painters, and chatting up the nation’s most notable personalities.

Yet, to be well-born back when the United States was young cut two ways. For the aristocratic Custis, it meant flung-open doors and a lifetime of answering to a world-famous name. And lofty expectations. Custis could have used his special privileges to scale new heights of accomplishment, in the manner of, say, John Quincy Adams, the sixth president who “descended from glory” from another president. Or he could have squandered his life in the manner of, say, John Payne Todd, the adopted son of President James and Dolley Madison, who traumatized his family with dissipated years of drinking and gambling.

Like many upper-crust peers, Custis struggled to find focus when he was sent away to not one, but three of the nation’s elite colleges. His failures nearly broke the heart of George Washington, whose own self-administered education left him brimming with a desire to raise a young classics scholar.

But Custis, whose father’s untimely death after the 1781 battle of Yorktown left him in need of infant care (his mother was preoccupied with other children), displayed a knack for driving the nation’s first president to distraction.

A remarkable series of letters between George Washington and Custis at his quarters at what became Princeton University, as well as St. John’s College in Annapolis, survives. Replies from the callow Washy, along with Washington’s anguish-filled missives to the youth’s stepfather David Stuart, are in the archives, as are the tactful exchanges between the tuition-paying Washington and the presidents of those colleges. These dialogues reveal the great man at his most vulnerable.

Early Disquietude

As a boy, Custis was assigned a succession of tutors - among them, Washington’s personal secretary Tobias Lear, at Mount Vernon and during the First Family’s time living in New York City and Philadelphia. But his chief influence was Washington himself, who gave him advice on everything from mealtime punctuality to farming techniques to the treatment of slaves, as Custis would detail in his posthumously published memoir.

Ironically, Washington’s struggles to mentor the errant Custis echoed the nearly identical behavior of the boy’s father, John Parke Custis, whom Washington also step-parented after marrying Martha. In the 1760s, the young veteran of the French and Indian War expressed his wishes that his stepson (nicknamed Jacky) could enjoy the formal classical education that he himself lacked (though the diligent Washington could recite Shakespeare).

At Mount Vernon, Washington prepped Jacky by buying him expensive books and hiring a Scottish tutor named Walter Magowan. When Jacky turned 14, Magowan recommended a boarding school run by the influential educator Jonathan Boucher, outside Fredericksburg. But Jacky failed to impress, embracing horsemanship more than scholarship and frequently forgetting his grammar. His attendance record was dismal. So, Boucher eased the pressure on Jacky to master the works in Latin and Greek, recommending instead that Jacky take the gentleman’s Grand Tour of Europe. At this, Washington balked, exclaiming, “He knows nothing of French.”

It then was arranged for Jacky to begin studies at King’s College in New York City (now Columbia University). But soon, he got grew distracted by visits to Prince George’s County, Maryland, where he courted the rich Eleanor Calvert. Rather than pursue a degree, Jacky at 20 married 16-year-old Calvert in 1774, and settled along the Potomac for a life of luxury. He continued as a source of worry to Washington in the run-up to the American Revolution.

Jacky’s son Washy would cause those same worries after our first president retired to his much-longed-for Virginia home. Under Washington’s wing, the boy grew up on conversational terms with early America’s luminaries, from Lafayette to “Light Horse Harry” Lee. There were high hopes. In Edward Savage’s famous painting of the nation’s first presidential family, the long-haired boy at age eight is standing next to a seated George Washington, and Washy’s hand rests imperiously on a globe. Custis’ elders might have wondered if that gesture foretold far-reaching vision.

“You are now extending into that stage of life when good or bad habits are formed,” President Washington wrote Wash on November 28, 1796, the eve of the youth’s first journey to a distant college, “when the mind will be turned to things useful and praiseworthy, or to dissipation and vice.”

Washy’s schooling in Philadelphia — Tobias Lear had arranged for him to commute to the College, Academy and Charitable School, the preparatory school that would later feed into the University of Pennsylvania — had produced mixed results. “I clearly see that he is on the high road to ruin,” Lear warned as early as 1791, citing the boy’s having been “born to such noble properties … and the servile respect the servants are obliged to pay him.” But what to do? “The president sees it with pain, but, as he considers Mrs. W’s happiness bound up in the boy, he is unwilling to take such measures as might reclaim him, knowing that any rigidity towards him would perhaps be productive of serious effects on her.”

Wash’s grandmother Martha, in 1794, wrote to her niece Fanny Bassett Washington of her own anxiety: Washy is “as constant as the day comes, but he does not learn as he might if the master took proper care to make the children attentive to their books.” She also blamed the problem on Wash’s many friends in a metropolis full of distractions. “My dear little Washington is not doing half as well as I could wish … and we are mortified that we can’t do better for him.”

Anguish at Princeton

There followed a three-year struggle on two campuses — a generation-gap drama that Custis and his own daughter in later life would lay open in their joint memoir.

George Washington had spent years creating an extensive library at Mount Vernon. Of special importance to him was Latin. To educate his charges, he considered Yale, William and Mary, the Alexandria (Virginia) Academy in which Washington had invested, and Harvard.

Instead, in 1796, 15-year-old Custis was enrolled in the sophomore class at the College of New Jersey (later called Princeton). There, at Nassau Hall, he joined 87 other students, paying eight pounds sterling per year for tuition and rent. He enjoyed being roommates with Cassius Lee, the son of Richard Henry Lee, and he joined the Whig Society. In the spring of 1797, Custis received ceremonial pistols and a sword from his step-grandfather, who knew Princeton’s president, the Reverend Samuel Stanhope Smith. That clergyman, sympathetic to the anti-slavery movement, would give Custis personal attention and a classical curriculum.

Early in his time at the college, Custis wrote to Washington that he was flourishing in reading Roman history, translating French, mastering geography, and studying the philosophy of David Hume. “Arithmetic, I must confess, I have not made as much progress as could be expected, owing to a variety of circumstances, and the superficial manner in which I first imbibed the principles, but the ensuing summer shall make up the deficiency,” he promised.

Princeton instructors reacted less favorably. Reverend Smith wrote a negative report directly to George Washington. In 1797, the Pater Patriae replied to say that Smith’s latest letter “filled my mind (as you naturally supposed it would) with extreme disquietude ... From his infancy, I have discovered an almost unconquerable disposition to indolence in everything that did not tend to his amusements.”

Custis assured his benefactor that he was studying Joseph Priestley’s lectures on history, English history, and the poetry of Tobias Smollett. On one occasion, he expressed alarm that he hadn’t heard directly from Washington, but the dreaded threatening letter finally came. It appeared to prick Washy’s guilty conscience, though the text is lost to history.

From Nassau Hall, a chastened Custis replied: “My very soul, tortured with the sting of conscience, at length called reason to its aid and, happy for me, triumphed; the conflict was long doubtful until at length I obtained the victory over myself and now return like the prodigal son a sincere penitent. That I shall ever recompence you for the trouble I have occasioned is beyond my hope. However, I will now make the grand exertion. I will now show that all is not lost and that your grandson shall once more deserve your favor.”

But he soon took a break from classes, and weeks later acknowledged to Washington his lack of discipline. “If in any way or by any means I depart from your direction or guardianship, let me suffer as I and such an imprudent act deserve,” he wrote in 1797.

To his lazy step-grandson, Washington gave some ground, writing that “it is not my wish that, having gone through the essential, you should be deprived of any rational amusement afterward; or, lastly, from dissipation in such company as you would likely meet under such circumstances, who, but too often, mistake ribaldry for wit and rioting, swearing, intoxication, and gambling, for manliness.”

Welcoming the boy’s contrition, Washington assured Wash that the teenager’s letter had “eased my mind of many unpleasant sensations and reflections on your account … and if your sorrow and repentance for the disquietude occasioned by the preceding letter, your resolution to abandon the ideas which were therein expressed, are sincere, I shall not only heartily forgive, but will forget also, and bury in oblivion all that has passed.”

The young Custis’ ambitious practice of writing independently about current events to his stepfather Stuart, his former tutors Lear and Zechariah Lewis, and his brother-in-law irked Washington. Initially, he assured the young student: “Far be it from me to discourage your correspondence with Doctor Stuart, Mr. Law, Mr. Lear or Mr. Lewis.” But Washington later wrote Lewis himself urging him to “impress upon Wash’s mind” the importance of study. He described his ward as distracted by “an indolent temper, amusements - at present, innocent but unprofitable.”

Like most youth, young Custis reveled in social life. In July 1797, he described his leisurely doings at Princeton. “The Fourth July was celebrated with all possible magnificence. We fired three times 16 rounds from a six-pounder and had public exhibitions of speaking,” Washy wrote to Washington. “At night, the whole college was beautifully illuminated. My ideas of impropriety proceeded from a distaste of such things during a recess from them, as I was confident all relish for study would be lost, after such enjoyment, for there is a difference in the minds being entirely taken off an object, to which it can return with increased vigor.”

Classes resumed, and Custis assured Washington that he was “now engaged in geography and English grammar…. The senior class will leave college in about a fortnight, and we shall become junior or second class, not in studies, as we do not commence mathematics until next session.” By then, it may have been too late for the lapsed scholar.

On September 7, 1797, George Washington Parke Custis was suspended by the full faculty. Decades later, his daughter wrote in their memoir that “we know not why Mr. Custis was removed from Princeton.”

It wasn’t until the 20th century that the mysterious reasons were sketched by a scholar reading the minutes of the college faculty: “Mr. George W. Custis having been guilty of various acts of meanness & irregularity, & having endeavored in various ways to lessen the authority & influence of the faculty… was suspended and ordered to leave the college.”

Washington had no choice but to settle the unpaid tuition. He sent the college president a note saying that Custis “will have himself only to upbraid for any consequences which will follow.”

Distractions in Annapolis

Back at Mount Vernon, the wayward Custis resumed his leisured life, enjoying hunting and visits to the racetrack.

But the retired president hadn’t given up on his schooling. In Annapolis is the campus of St. John’s College, where the Washington family had sent other members. Its rector, John McDowell, an attorney and classical scholar, could offer special attention, and the town — where Wash’s father Jacky had been distracted — was well-policed. “There is less of that class of people which are baneful to youth in that city, than in any other,” Washington wrote to David Stuart, who had married Custis’s widowed mother.

Neither of the men was confident in the 17-year-old’s maturity. “His habits and inclinations are so averse to all labor and patient investigation,” Stuart wrote. “Not much can be expected from any plan.”

In January 1798, Stuart accompanied Wash on a trip to Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay, and the correspondence with his eminent step-grandpa continued: “I was so fortunate to get in with a Mrs. Brice, a remarkable, clever woman, with whom I live and am well contented,” the student wrote Washington in March, referring to his landlady Julianna Jennings Brice. Wash said he was “pursuing the study of Natural Philosophy, and hope to distinguish myself in that branch, as well as others. Arithmetic I have reviewed, and shall commence French immediately with the professor here.”

Again writing discreetly, Washington warned the school head McDowell that “Mr. Custis possesses competent talents to fit him for any studies, but they are counteracted by an indolence of mind which renders it difficult to draw them into action.”

Mr. McDowell replied on March 8: “His proficiency in literature does not indeed appear to be adequate to the opportunities which he has enjoyed and the time that he has spent at school. But, with diligence and application, he may yet acquire a good stock of valuable and ornamental knowledge.”

To Custis, Washington was tactful. “The wise man you know has told us,” he wrote, “that there is a time for all things; and now is the time for you to lay in such a stock of erudition as will effect the purposes I have mentioned. Let these continue to be your primary objects and pursuits.”

Custis by now was expected to write home every fortnight detailing his academic progress. The youth reported cheerfully on April 2: “I am very happily situated, perhaps better than many.” Addressing the “principles” Washington had recommended, he wrote, “It is them that elevate the soul and prompt us to good works. I conceive that misfortunes are intended as awful example for us to profit by and are proportionate to the degree of prevalence which the passions have over us. What, then, could have been a greater misfortune to me than your displeasure? What a greater happiness than your confidence?”

Custis was getting up for 6:00 a.m. classes and promising, “I attend college regularly, and am determined that nothing shall alienate my attention.”

But a premature request for money rubbed Washington the wrong way. On May 10, the former general reminded him that Mr. Stuart had brought him a trunk and a “quarter’s board paid in advance, except for your washing, and books when necessary. I am at a loss to discover what has given rise to so early a question.”

Custis backtracked in response: “I didn’t not mean to insinuate that I was actually in want, but supposed you had placed money in the hands of someone to whom I might apply.”

Washy added that he had “opened accounts with a shoemaker, a tailor…. I took a couple of pieces of nankeen for summer breeches and a gingham coat,” he wrote. “Far from being addicted to frequent taverns, I am not fond of such sociability and assure you that I have not spent a farthing in that way. Tis true that I am fond, when among friends at my own time, to enter into a little superfluities, such as toddy, etc. but farther, I sacredly deny any dissipation.”

Washy also admitted that, like his father Jackie, he loved the local Maryland families. “I am charmed with Annapolis and also its inhabitants and have received every attention from them,” he wrote in May.

More threatening to his step-grandfather’s support were rumors that Custis had become serious with a local woman: “We have with much surprise been informed of your devoting much time to paying particular attention to a certain young lady of that place!” Washington wrote him. Having not heard from Custis in weeks (their letters crossed in the mail), G.W. admonished, after a world-weary warning against preoccupation “with the gratification of passions,” adding, “I am sure it is not a time for you to think of forming a serious attachment of this kind which might … involve a consequence. of which you are not aware.”

Custis defended himself. He had disclosed to his mother earlier that he had “solicited the girl’s affection, and hoped, with the approbation of my family, to bring about a union at some future day.” But now he told Washington that the report of an engagement “is strictly erroneous. That I gave her reason to believe in my attachment to her, I candidly allow, but that I would enter into engagements inconsistent with my duty or situation, I hope your good opinion of me will make you disbelieve.”

By mid-summer, Custis claimed he had nearly finished reading six books of Euclidian math and was anticipating the summer break in late July. He would flatter his benefactor, congratulating Washington on his new status as commander-in-chief for a possible war with France: “Let an admiring world,” the boy wrote, “again behold a Cincinnatus springing up from rural retirement to the conquest of nations, and becoming the Father of His Country.”

Custis’s final days at St. John’s, before he took a stagecoach home, were marked by a small confession he sent Washington on July 23: “The only object I apologize for is an umbrella, which I was unavoidably obliged to procure, as I lost one belonging to a gentleman.”

Washington had been preparing for the worst, complaining to Custis’ stepfather and mother. “If you or Mrs. Stuart could by indirect means, discover the state of Washington Custis’s mind, it would be to be wished,” he wrote in 1798. “He appears to me to be moped & stupid, says nothing — and is always in some hole or corner excluded from company.”

Mr. McDowell tried to be encouraging. The educator wrote Washington that Custis “has of late been much more attentive to business; and has applied himself to the study of Euclid with such advantage, that he is now pretty well acquainted with as much of the elements as is usually read in our schools.”

In early September, as the academic year began, Washington asked McDowell to admonish Custis “seriously of his omissions and defects.” He asked to be informed “if you should perceive any appearance of his attaching himself, by visits or otherwise, to any young lady of that place, that you would admonish him.”

The retired president was at his wit’s end: “There seems to be in this youth an unconquerable indolence of temper, and a dereliction, in fact, to all study,” he wrote McDowell, confessing to having no precise recommendation on the youth’s studies. “It must rest with you to lead him in the best manner, and by the easiest modes you can devise, to the study of such useful acquirements as may be serviceable to himself, and eventually beneficial to his country.”

Wash would never return to campus. To end the ordeal, George Washington wrote to Martha’s brother Bartholomew Dandridge to say he that found it “impracticable to keep him longer at college with any prospect of advantages; so great was his aversion to study; though addicted to no extravagant or vicious habits, but from mere indolence and a dereliction to exercise the powers of the mind.”

The Errant Student Rallies

The academic failures trailed Custis for life. Even his daughter Mary, in their late-life memoir published in 1860, diagnosed Custis’s upbringing under Washington as limited: “The public duties of the veteran prevented the exercise of his influence in forming the character of the boy, too softly nurtured under his roof, and gifted with talents,” she wrote, “which, under a sterner discipline might have been made more available for his own and the country’s good.”

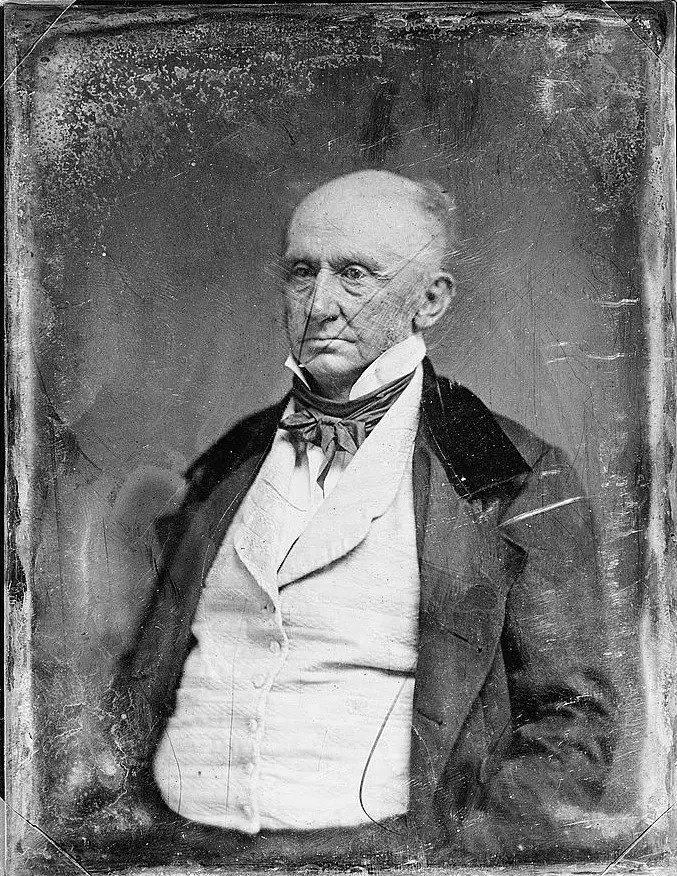

Yet, after reaching age 21, Custis rallied. He created Arlington House outside the new capital, a Greek Revival tribute to the Pater Patriae designed by noted British architect George Hadfield. He embarked on agricultural reforms, experimenting with new breeds of sheep. He fought the British in the 1814 Battle of Bladensburg. He published essays on his conversations with the Marquis de Lafayette while escorting him on portions of the Frenchman’s 1824-25 Grand Tour of the young United States. He wrote patriotic plays produced in theaters up and down the East Coast. He painted battle scenes (appreciated more for their historical detail than their beauty), and was a consultant to accomplished painters and biographers of George Washington. It seems that Washington’s admonitions to the youth had sunk in, after all.

But the plantation gentleman Custis also continued his ownership of some 200 slaves, 60 at Arlington House and another 140 on two plantations on the Pamunkey River east of Richmond. In many ways, he was a conventional enslaver, pursuing runaways and profiting from crops (more on his southern plantations than at Arlington House). And he was active in the American Colonization Society, whose agenda was to recruit free blacks to deport to Africa.

But, according to witnesses, Custis was kinder to his slaves than was his son-in-law Robert E. Lee. Of course, Lee’s attitudes toward slavery were destined for national impact, and he, too, had grown up with a small contingent of enslaved domestics. Lee saw eye-to-eye with his wife on the Christian commitment to allow the enslaved to read and worship. But, as an Army man, he was not at liberty to embrace the Colonization Society.

As for Custis, the most jarring story of his handling of slavery involved illicit fatherhood. The tell-tale event was the birth, circa 1803, of a mixed-race child to an enslaved maid named Arianna Carter (1776-1880). Evidence, once hushed up, but resurfaced in the 20th century, largely confirmed that Custis was the father. (The recently renovated National Park Service exhibits at Arlington House showcase this fact.)

Custis died in 1857. It should come as no surprise that he would emulate his famous step-parent by calling in his will for the emancipation of his slaves. But, as the Father of His Country had stipulated in his own will regarding his own slaves, only after his death. The language specified that this must occur within five years, a requirement that frustrated Robert E. Lee, who, as executor, sought to recover enough profit from his farm operations to honor other bequests. Lee would frustrate the enslaved workers by taking the entire five years.

The point was rendered moot by the Civil War and the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. But it seems that Custis had frustrated his own heirs, as well as his human property. Just as he, as a youth, had frustrated his famous step-grandfather.