From ancestral homes of George Washington to World War II runways, there are many sites in the U.K. where you can encounter American's past.

-

Summer 2022

Volume67Issue3

Weathered and time-worn, the detail in the crest’s carving can only just be discerned: the faint outline of a shield-like shape within which sit some horizontal bars and the shadow of what once must have been three stars. Now safely ensconced in the interior of St. Oswald’s – a 15th century church in the village of Warton, north Lancashire – the crest had originally been attached to the exterior of the tower and had felt the full force of the wind and rain that barrels in from the Irish Sea.

Sometime in the early 19th century, it was covered over with plaster, only to be rediscovered by workmen conducting repairs in the 1880s. For those who were chipping away with hammer and chisel, it must have been a remarkable moment; here was the crest of a local family of substance, one which had clearly had the money and power to carve their emblem into a medieval parish church.

And the name of this family, these one-time denizens of the rugged English north country? Washington.

Today, the keen-eyed visitor will discover that there are in fact several places in Warton that record a local connection to the family of George Washington, the man who in 1789 became the first president of the United States of America. In the churchyard, for instance, lies another – the grave of Thomas and Elizabeth Washington, the last of that name to be buried in the shadow of St. Oswald’s.

A walk down the village’s main street reveals the local pub (The George Washington, of course) as well as “Washington House,” a 17th century property at which the family had once lived. It's a fascinating architectural legacy of a now-distant transatlantic connection.

Warton is by no means the only British community featuring markers and memorials to the Washingtons. Others can be found at Washington Old Hall in County Durham, at Purleigh and Maldon in Essex, and at Sulgrave Manor in Northamptonshire (the latter is another of the Washington ancestral homes).

And it’s not just the Washingtons. In fact, the interested traveler can find among Britain’s towns and villages numerous locations suggestive of the deep historical connections linking the United States and United Kingdom, connections which run from the earliest days of colonial settlement through to the twentieth century and beyond. Here is a record in stone and stained glass of what Winston Churchill famously declared to be an unbreakable “special relationship.”

Pilgrim goodbyes

In the village of Immingham, near the banks of the River Humber on the northeast coast, can be found an unassuming monument to a daring seaborne escape one cold and stormy evening in 1608. At the center of the story was a group of Protestant Separatists, most of whom hailed from the surrounding counties of Lincolnshire and Yorkshire.

Persecuted for their faith and keen to establish a community in which they might find the freedom to worship as they saw fit, these Separatists had set upon a plan to take a ship east, across the North Sea, to Holland, where they hoped to find a welcome amongst fellow Protestants. They had already tried once before, in 1607, from a creek near the fenland town of Boston. But they were betrayed to the local authorities and a large part of their group were subsequently arrested and imprisoned. So they tried again, this time choosing a “large comone” located “Betweene Grimsbe and Hull” (in the words of Willian Bradford).

Their tale would perhaps have drawn relatively little interest but for one crucial fact: these religious refugees were the so-called “Pilgrim Fathers,” the very same community that took to the seas again in 1620, this time heading west on the Mayflower to the New World.

The monument at Immingham is one of several such structures in Britain dedicated to this history. Others can be found in Plymouth (the Mayflower Steps) and Southampton, as well as at Fishtoft, just a few miles east of Boston. Unveiled in 1957, this latter monument has a plaque declaring that “Near this place in September 1607, those later known as Pilgrim Fathers were thwarted in their first attempt to sail to find religious freedom across the seas.”

Read “Mayflower's Place in History”

by Nathaniel Philbrick in our October 2020 issue

Close by, in the town’s striking church of St. Botolph, a stained-glass window similarly celebrates local connections to those Puritans who sailed west four centuries ago (the window depicts John Cotton, a local religious leader who migrated to Massachusetts in 1633).

Pocahontas (née Matoaka) becomes “Rebecca”

The English settlement of North America was of course a colonial enterprise which had profound consequences for indigenous communities. Indeed, in the years that followed the arrival of English colonists, some indigenous people – often captured and coerced – would themselves make a similarly epic transatlantic journey, albeit this time from west to east. Among them, famously, was a young woman mythologized in colonial history as Pocahontas, but who was in fact known in her community as Matoaka.

A member of the Powhatan Confederacy in what is now Virginia, the “real” Matoaka remains an elusive figure, her story too often refracted through an imperial, colonizing, and male lens. What we do know is that in the winter of 1607, she encountered an Englishman – Captain John Smith (educated, incidentally, in the Lincolnshire town of Louth, just twenty miles south of Immingham) – who had arrived in her Powhatan village as a prisoner.

What followed has been much discussed and debated, with the only source being Smith himself, and even his was authored at some years remove (in 1616). At the story’s center was an act of romantic self-sacrifice, with Smith claiming that “Pocahontas” – as he called her – had heroically saved him from execution by a Powhatan warrior intent on dashing out his brains. The veracity of this tale is highly questionable, not least because Matoaka would have been around 11 at the time. But it has been told and retold over the centuries, garnering the sheen of legend.

It seems that, in the years that followed, Matoaka had many other encounters with English settlers as the two communities engaged in barter, negotiation, and occasional conflict. In 1613, she herself was captured, ransomed for the return of English prisoners held by the Powhatan, and taken to Jamestown. It was there that she met yet another Englishman – a widower named John Rolfe – with contemporary (and, once again, English) sources declaring that they fell in love, though, as with her previous encounter with John Smith, this is a narrative that clearly served the interests of English settlers: it converts a story of captivity and dispossession into a romance.

Matoaka was baptized into Christianity in spring 1614, took on the name “Rebecca,” and married Rolfe soon after. In 1616, and with a dozen other members of the Powhatan chiefdom in tow, the newlyweds crossed the Atlantic. On arrival in Britain, the Rolfes toured the country and were feted by royalty.

Their visit, though, was relatively brief, and by March 1617, they were already preparing for the journey back to Virginia. They did not get far, though. On board ship, Rebecca became seriously ill and was taken ashore at Gravesend in Kent. She died there on March 21 and was buried at St. George’s church.

It is a sad and somber tale, one full of pathos and marked by a frustrating absence of detail. What did “Rebecca” think and feel during her tour of Britain? Was her original encounter with Smith as he – self-servingly – had described it? Had she really “fallen in love” with Rolfe, or was the truth far more complex? By what name did she in fact call herself? Matoaka? Pocahontas? Rebecca?

For all these questions, the historical record preserves the exclusions which so shaped the world in which Matoaka lived. The sources that survive were authored, invariably, by white Englishmen, figures who had little interest in recording the voice of an indigenous woman of the Powhatan people. What we know of her visit to Britain is very limited. But we do know that she came; we do know that she toured the country; and we do know that she was used as a symbol among English settlers to claim that their presence in the Americas was welcomed by indigenous communities.

This claim on Pocahontas – on Matoaka – is recorded in Britain in two memorials. One of these is at St. George’s in Gravesend, where the exact location of her grave has unfortunately long since been lost (even despite an official search conducted in 1923 by a Virginia antiquarian). Inside the church are a commemorative tablet (erected in 1896) and a memorial window dedicated in 1914 by the National Society of Colonial Dames. Outside stands a statue of Pocahontas unveiled by the Queen in 1957 (a copy of one in Jamestown). It is a depiction of Pocahontas just as early twentieth-century stereotypes would have her – a serene “Indian Princess” complete with a feather in her hair.

One other location in England has a memorial to Pocahontas: Heacham in Norfolk, the family seat of the Rolfes which she visited in the winter of 1616. Unveiled in 1933 "to mark a picturesque episode in the history of two nations," the memorial inside the parish church shows Pocahontas in seventeenth-century English dress. It reminds us of a salient fact: that her story and image are bound up with the history of empire and colonization.

This is a history that might on occasion appear to have certain “romantic” qualities; but it should – it must – also force us to encounter difficult truths. Who exactly was “Pocahontas”? Had she travelled to Britain willingly? And what did she and her Powhatan compatriots think when they first saw the shores of the Old World? Alas, we do not know.

Memories of other great Americans

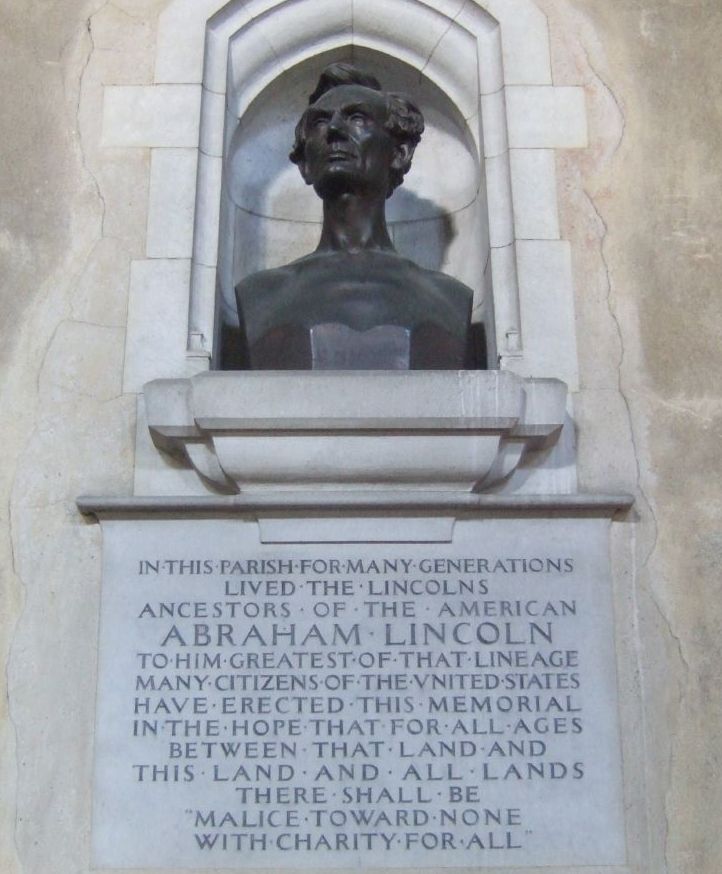

Forty miles southeast of Heacham is the village of Hingham. Quaint and quiet, it appears today as a rather unremarkable place, one of many such villages dotted among the East Anglian countryside. But, just like Heacham, it claims a transatlantic connection based on a particular person, one perhaps even more famous than the seventeenth century Powhatan Princess. For Hingham is the ancestral home of Abraham Lincoln; this is the very place from which the Great Emancipator’s paternal ancestor, Samuel, departed in 1637, seeking a new life in the New World.

Hingham’s Lincoln connection was not fully established until the early twentieth century, a period characterized by a growing transatlantic interest in matters of ancestry and, significantly, "race." Indeed, this was an era in which many contemporary elites sought to celebrate Britons and Americans as members of, so they claimed, a single “Anglo-Saxon” family.

This was the context in which Lincoln’s family line – pursued by energetic genealogists for several decades – was finally traced to a rural Norfolk village, a connection duly commemorated in 1919 by the placing of a bust of the 16th President in the parish church (it was a gift of his son, Robert Todd Lincoln). Crucially, this was not an isolated event. The dedication of this bust was part of a broader contemporary British obsession with the Great Emancipator.

The earliest evidence of this obsession can be found in Edinburgh, where a memorial dedicated to those Scottish-Americans who fought in the US Civil War was unveiled in 1893. Located in Old Calton Cemetery, the memorial is dominated by a sculptural depiction of Lincoln, the first of its kind in Britain. But it was in the first two decades of the twentieth century that British interest in the Illinois lawyer intensified, ultimately leading to the creation of two figurative statues.

The first was unveiled in Manchester in 1919. Dedicated by the American Ambassador (John W. Davis), the statue – a copy of one by George Grey Barnard, the original of which is in Cincinnati – was first located in the city’s Platt Fields Park. It was later relocated (in 1986) close to the Town Hall, where it stands today in the aptly named Lincoln Square.

Manchester was a fitting location. Famously, in 1863, Lincoln had sent his thanks to the local citizens after they had declared their commitment to the Union cause (even in the face of the widespread unemployment which accompanied the blockade of the South and its cotton exports). Indeed, the city had been at the forefront of nineteenth century British anti-slavery activism and had even welcomed Frederick Douglass in 1846. A powerful orator, Douglass had delivered a blistering attack on slavery from Free Trade Hall.

In subsequent years, other prominent African American activists traced a similar path. Ida B. Wells came to Manchester in the spring of 1894, giving a lecture from Temperance Hall condemning racial violence and lynching.

The great W.E.B Dubois also graced the city – in October 1945, he arrived in Manchester as a delegate to the Fifth Pan-African Congress, an important anti-colonial conference which met at various locations in the city, including Chorlton Town Hall (a plaque on the façade records the occasion).

The second statue of Lincoln erected in Britain after World War I was placed in a still more prominent location – London, within view of the Palace of Westminster. A copy of a statue by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (the original of which stands in Chicago), it was unveiled on a rainy day in 1920 before a crowd of dignitaries and diplomats. Where Barnard’s statue shows Lincoln as a working-man (an eminently appropriate depiction for the great industrial city of Manchester), Saint-Gaudens’ depicts him as a solemn statesman.

Of course, the man who led the United States during the Civil War is by no means the only American president depicted on the London landscape. Not too far away, near the site of the former American Embassy at Grosvenor Square, is a statue of Franklin Roosevelt (unveiled by his wife, Eleanor, in 1948), and another of Dwight D. Eisenhower in the garb of wartime Allied Commander. A statue of Ronald Reagan also once stood nearby, though it is currently in storage while the site is being redeveloped.

Meanwhile, close to Winfield House, the official residence of the US Ambassador to the Court of St. James, is a commemorative bust of President Kennedy, felled by an assassin’s bullets in 1963. His primary British memorial is at Runnymeade, the location made famous by the signing of Magna Carta.

And overlooking Trafalgar Square, just outside the National Gallery, stands the man with family ties to Warton in Lancashire: George Washington. A gift of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the statue was dedicated in June 1921 and was followed just a few days later by the formal establishment of his ancestral home – Sulgrave Manor in Northamptonshire – as a “shrine” to the Anglo-American alliance. The manor remains as such to this day, proudly flying the Stars and Stripes from among the fields and lanes of rural England.

Other prominent figures of the Revolutionary era have likewise been memorialized in Britain. A statue to Thomas Paine, the chief propagandist of the Revolution, is outside the Town Hall in Thetford Norfolk, the place of his birth, and a simple marker in his memory can also be found in Lewes, East Sussex, where he once worked as a taxman.

Read “Times That Try Men’s Souls”

about Paine in the Spring 2022 issue.

Benjamin Franklin’s house for sixteen years at 36 Craven Street in the heart of London is now a museum. It is Franklin's only remaining home and is a Grade-I listed building, with many of its original features, including the staircase, floorboards, wall paneling, and fireplaces. It was restored in the 1990s, and an educational center was added with support from the American donor Robert H. Smith.

In Bath, one of several places that took in American loyalists after Washington’s victory at Yorktown, the American Museum is worth a visit Its gardens are modeled on those at Mount Vernon. With a remarkable collection of folk, decorative arts, and cultural objects, the museum interprets diverse American traditions to the people of Britain and Europe. It claims to be the only museum of Americana outside the United States.

In Dumfries, the birthplace and former home of John Paul Jones, "Father of the US Navy," is preserved as a museum. In the Cumbrian port of Whitehaven, a memorial records his famous (though unsuccessful) 1778 attack on British merchant ships.

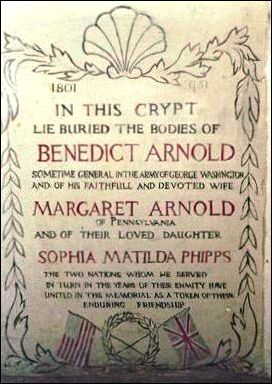

Even Benedict Arnold – reviled as the worst traitor in American history – has in recent years been the subject of commemoration. In the late 1980s, a local Briton successfully petitioned Westminster Council to place a plaque on Arnold’s London home, where he died in 1801. And in St. Mary’s Church in Battersea – which Arnold attended when he lived in the city – there's a stained glass tribute to the one-time general in the Continental Army; it was unveiled during the bicentenary of Independence in 1976.

In the crypt, meanwhile, is a marble tombstone to both Arnold and his wife, Margaret Shippen. Placed there in 2004, it notes that, while Arnold served both the United States and Great Britain “in the years of their enmity,” today the two countries nonetheless stand “united in enduring friendship.” Rather unusually, the Arnolds now share the space during the week with a kindergarten!

Very occasionally, there are also some glimpses of the Anglo-American antagonisms of the post-Revolutionary period. Take, for example, the former Chesapeake Mill at Wickham in Hampshire, the skeleton of which is made from the timbers of the USS Chesapeake. Captured by the Royal Navy in 1813 (during the War of 1812) the Chesapeake – built in Virginia in the 1790s – was subsequently taken into British service before being broken up and sold in 1819.

One local, John Prior, clearly saw the potential, purchasing several solid timbers to provide the structural integrity so crucial to his mill (a piece of which was recently given to Secretary of the Navy Kenneth Braithwaite during a visit to Britain in 2020). The building remains today, although it ceased operation as a mill back in the 1970s.

Allies in War

As their chronology suggests, the Lincoln and Washington statues were in many respects memorials to the Anglo-American alliance forged during World War I. However, the most prominent American war memorial established in Britain after 1918 is at Brookwood in Surrey. Famous as the site of the London Necropolis (the largest cemetery in Britain), after World War I, it became a place of burial for service personnel. First came the Imperial War Graves Commission, which is responsible for all British and Imperial dead. And then came its transatlantic counterpart, the newly created American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC).

Officially dedicated in 1937, the ABMC cemetery at Brookwood is arranged in accordance with its evolving practice and protocol, with close attention to landscaping and horticulture and with a standard design of the headstones. A Latin Cross of white marble for Christian dead and a white marble Star of David for their Jewish comrades are all set within a perfectly manicured lawn. Sadly, of course, it would not be the last American war memorial established on British shores, and subsequent events soon resulted in the creation of another American military burial ground.

Indeed, within just six years of the dedication ceremony at Brookwood, a new American military cemetery was being laid out not too far away in Cambridgeshire. This new cemetery – at Madingley, close to the ancient university city of Cambridge – was far larger: where just 468 service personnel were interred at Brookwood, the number at Madingley is 3811. To visit is to be moved by its scale and beauty. The carefully designed setting includes a Wall of the Missing (carved with 5,127 names, one of which is Joe Kennedy, the older brother of JFK, who was killed in a plane explosion over eastern England in 1944); a reflecting pool modeled on the one in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.; and a Memorial Chapel.

Further afield, among the village greens and churchyards of England’s eastern counties, the attentive visitor will encounter yet more signs of the wartime American presence in this region: a solid pillar of granite, a stained glass window, or a simple plaque recording the sacrifices of those young American airmen who were sent to battle in the wide blue yonder.

The Archive of the Feet

The memorials and monuments detailed above reveal a key feature of the twentieth-century Anglo-American relationship: that it lives in speech and policy, but also in brick and bronze and glass. It has been articulated in oratory, but also in architecture. Take a look the next time you’re this side of the pond and, if you can, take the time to track down some of the sites of American heritage here in Britain. Some are hidden along quiet country lanes and some stand proud on urban thoroughfares; all reveal a fascinating history stretching across centuries, one that is perhaps best explored by what one scholar has called the "archive of the feet."

The pages of history are there to be read; you’ve just got to head out for a walk.