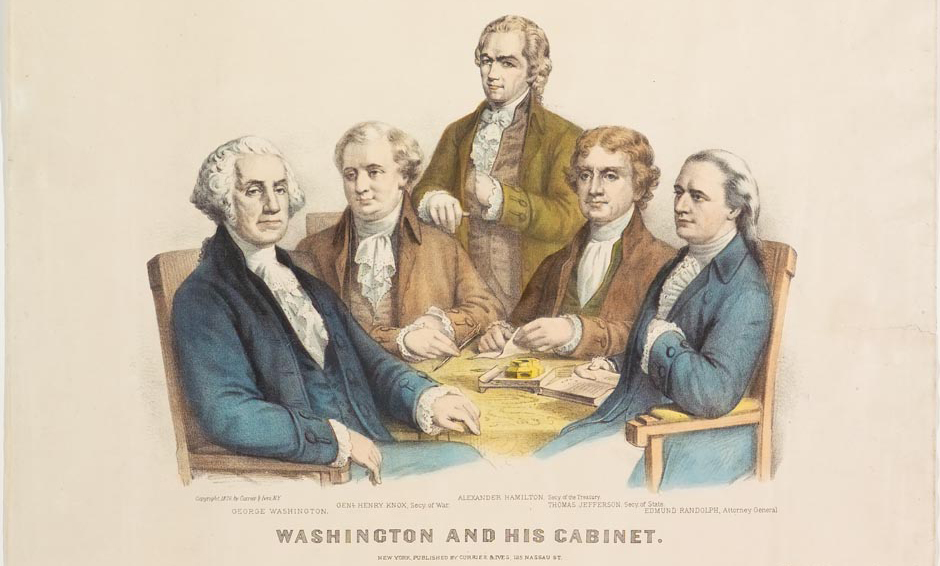

Fierce debate among early political factions led to many allegations of misdeeds and abuse of power in Washington's administration, but there was no serious misconduct.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

Historians have reached no consensus in their interpretations of the administrations of George Washington and John Adams, but two statements can be made with little fear of contradiction. At the senior levels of the executive department during the first decade of the national government, there was no behavior that can unequivocally be described as misconduct in office. Yet there has never been a time in the American past when allegations of misuse of executive power and suspicions of administration motives have assumed a tone more extreme.

These paradoxical statements can be understood only by reference to the context of a distinctive age. The Federal Period was a stage in the American Revolution, the time when the Founders sought to put their political principles into effect on the national level. To them, this was a project for the ages, one that would determine the future of liberty in the world. Every important action had to be taken in light of revolutionary principle and with a view toward the many generations who would live with the results. The nature of the age thus shaped its leaders' conduct. It also made certain that their actions would be judged in the harshest light.

Washington and the men around him came to their national offices as heroes of a great revolution, their places in history already secure. Valuing so highly their reputations with the people and posterity, Presidents Washington and Adams and their advisers seldom slipped from a rigid standard of personal integrity and scrupulous regard for the laws.

As much, perhaps, as men can be, they were simply above the kinds of conduct that later generations have come to associate with the abuse of power.

There was one point on which most Americans did agree: it would be extremely difficult — perhaps impossible — to provide a single, republican government over so vast and varied a country. Certainly, each step at this beginning would have to be watched with the most conscientious suspicion, so that a hard-won liberty would not be lost. Such was the atmosphere of the Federal years, 1789-1801, and in this atmosphere it proved impossible for leaders to avoid the charge that their conduct was not only corrupt but deliberately inimical to the liberty they were sworn to preserve.

But this did not shield them from accusations such as few American leaders have ever had to hear. In 1789, when the federal government went into effect, Americans shared no agreement about what a federal republic should be like. The new constitution was a piece of parchment which a majority of the people may well have opposed. It provided, at best, only an outline of a working government, and the outline meant different things to different men.

"Corruption” is a hateful word in any age, but the word had larger meaning in the time of the Founders than it does today. To them, any uses of public trust for private ends were indications of a deeper malaise. Corruption referred not just to these practices, but also to a larger process of which they were commonly a part. The word suggested a progressive degeneration of the body politic, a process often compared with growth of cancer in organic bodies. There was nothing the Founders feared so much as corruption in their special sense. Once started, corruption was all but impossible to reverse. The state so infected ran its course to political death. And the revolutionary heritage assured the Founders that corruption was the normal direction of political change, the fate of every previous state.

In one of its aspects, the American Revolution was the last great expression of a current political thought that came down to the Founders from classical times. Transmitted to America by way of the English inheritance, this neoclassical politics sought a way to combine liberty with stability in a state. Following its precepts, the Founders believed that no simple form of government could achieve this end. Because men will pursue their selfish interests at other men's expense, no single man or single group of men — not even a majority — can be wholly trusted with the welfare of a state. Absolute control by a majority will prove oppressive to minorities just as surely as control by a single individual will prove oppressive to all the rest.

History will be an endless cycle of governmental degeneration, oppression, and revolt. Escape from instability and liberty for all depends on a form of government in which the powers of different branches and different principles are balanced against one another in a system of complicated checks. In this form only can the strength of a single executive be combined with wisdom and concern for the common good into a just and stable government where the law is supreme.

Even a balanced government must be constantly guarded against corruption or decay. It is hard to strike the proper balance between the parts, harder still to see that the original equilibrium is maintained. The very independence and self-interest which assure that each branch will check the others make it certain that each will also seek a larger share of power for itself. Success by any branch in the inevitable quest for larger power means constitutional decay. The government will increasingly approximate a simpler form. The rule of law will tend increasingly to become a rule of men, and liberty will be lost.

Thirteen years before the First Federal Congress assembled in New York, America had severed its ties with England. In no small part, independence had come because Americans had concluded that the supposedly balanced constitution of England had become an executive tyranny in disguise. By corrupting the members of Parliament, Americans believed the men around the King had achieved complete control. That done, the tyrants of Britain planned to destroy American liberty as well. The American Revolution was an effort to defeat this plot and to secure the lasting happiness of an independent people by once more returning to a government of laws — this time, a republican government, with equal rights and equal laws, which might be more secure against the ravages of conspiracy and decay.

The Federal Constitution was the last in a series of efforts to achieve a balanced government that would fulfill the republican ideal. To the Classic defense of checks and balances, its framers had added a further protection for liberty in the division between state and federal power. but no one could be certain that the experiment would succeed. The new government must become a fact. It must do so under the steady stare of a generation who could not yet define what “republicanism” would mean, but who had been reared and blooded in the belief that the balance between liberty and stability is a very fragile thing. These men had grown up in the conviction that governments are prone to decay. All their thought and experience taught them that power is subject to conspiratorial abuse. The administrations of Washington and John Adams, and to a lesser extent of the Jeffersonians which followed, are incomprehensible without an awareness of this heritage of thought.

Attacks on the President

In the early years of his presidency, Washington had not been subjected to direct assault. Critics began to close on the President himself only very gradually and with considerable caution, since Federalists had always found it useful to defend governmental policies by invoking hero's prestige. In time, however, it became increasingly difficult to deny that some decisions came from Washington, and a minority of Republicans concluded that they could destroy the policies only by damaging the President's prestige.

The first target was the Neutrality Proclamation of 1793, which many Americans considered a betrayal of revolutionary France. Few critics, as yet, impugned the President's motives. From the first days of the new government, however, one form of criticism had particularly angered the head of state. Some writers had periodically worried about the tone of the new government, denouncing a kind of pageantry that seemed better suited to a monarchy than a republican state. Robes for judicial officers, honorary forms of address for public officials, high government salaries, extravagant private entertainments, and celebration of the president's birthday had all been attacked. So had the president's official dinners and formal receptions, which too much resembled “courtly” levees.

At the end of 1792, “Mirabeau,” “Cornelia,” and other anonymous writers in the National Gazette mounted a campaign against these practices. Such criticisms provoked Washington's impassioned outburst against “that rascal Freneau” in a cabinet meeting in August, 1793. The president was infuriated by hints that he displayed monarchical leanings, although, to this point, most critics of the high tone of government would have agreed with Senator William Maclay: “the creatures that surround him would place a crown on his head that they may have the handling of its jewels.”

Another long stride toward involvement of the president in opposition charges came in the aftermath of the Whiskey Rebellion, when Washington included in his annual address to Congress a criticism of “certain self-created societies.” Reluctant though they were to challenge the President, even congressional Republicans saw this rebuke of the democratic-republican societies as a party act and a dangerous interference with the right to censure the government. Still, most critics avoided a direct confrontation. It was only when he signed Jay's Treaty that Washington wrote an end to his immunity to the sharpest barbs of critical assault.

To Republicans, Jay's Treaty was the penultimate confirmation of their fears that a “British interest” was involved in a Federalist conspiracy to destroy republican government in the United States. It was impossible to deny the president's agency in putting the treaty into effect, particularly after he refused on constitutional grounds to deliver papers relating to the negotiations to the House. Thus a minority of Republican writers deliberately set out to destroy the president's reputation with the people. Belisarius,” “Valerius,” “Pittachus,” and others filled the Philadelphia Aurora with direct attacks on the president, sometimes going so far as to advocate his impeachment. The New York Argus and Boston's Independent Chronicle joined the campaign, along with a few pamphleteers.

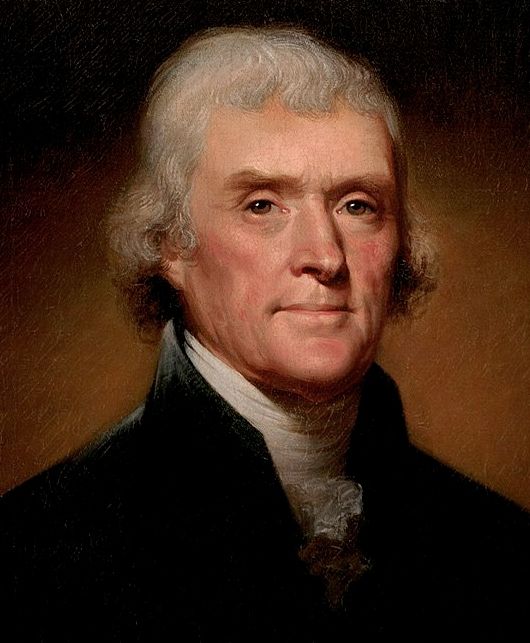

From France, Thomas Paine took a hand in the assault. Even Jefferson was involved, when a Federalist newspaper published his famous accusation that “men who were Samsons in the field and Solomons in the council ... have had their heads shorn by the harlot England.”

For more about the controversy over Jay's Treaty, see “Impeach President Washington!” by Michael Beschloss

Jay's Treaty occasioned the assault, but the Republicans reexamined Washington's conduct as a whole. They rewrote their history of the Federalist conspiracy in such a manner as to impugn the president himself. "Belisarius, for example, addressed the President directly, charging that his administration had entailed upon the country “deep and incurable public evils.” The administration had created a distinction between the people and the executive through monarchical pageantry, sanctioned the plunder of revolutionary veterans by avaricious speculators, mortgaged the revenue to an irredeemable public debt, formed a “monied aristocracy” by chartering a national bank, created a dangerous standing army, and incited the people to rebellion with excise laws. Now it had approved an unconstitutional treaty “deeply subversive of republicanism and destructive to every principle of free representative government.”

Would Washington, asked one of the most important pamphleteers, end his term “the tyrant instead of the savior of his country?”

Washington's last years in office were made an agony by such abuse. He was charged with exceeding his expense account. Old revolutionary forgeries were revived to impugn his patriotism. For a man whose sole remaining ambition was to retire, who felt he had sacrificed a lifetime to his country, the assault was absolutely insufferable. It was no consolation that his enemies probably damaged their own cause more than himself. It required considerable restraint, when he prepared his Farewell Address, to confine himself to warnings against the evils of faction, the threat of sectional confrontation, and the dangers of undue affection for a foreign state. But this was Washington's only public response to the opposition attacks.

Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.