At the end of the War for Independence, Philadelphia nationalists, together with disgruntled officers in the Continental Army at Newburgh, began a plot to challenge congress' authority. But can we really call it a conspiracy?

-

Fall 2020 George Washington Prize

Volume65Issue8

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist A Crisis of Peace: George Washington, the Newburgh Conspiracy, and the Fate of the American Revolution, by David Head (Pegasus Books).

On a cold morning in March 1783, the officers of the Continental Army read a letter that was circulating through their cantonment along the Hudson River. The officers considered the letter's call to do something soldiers weren't supposed to do: meet to discuss how to send an ultimatum to the civilian authorities in Congress.

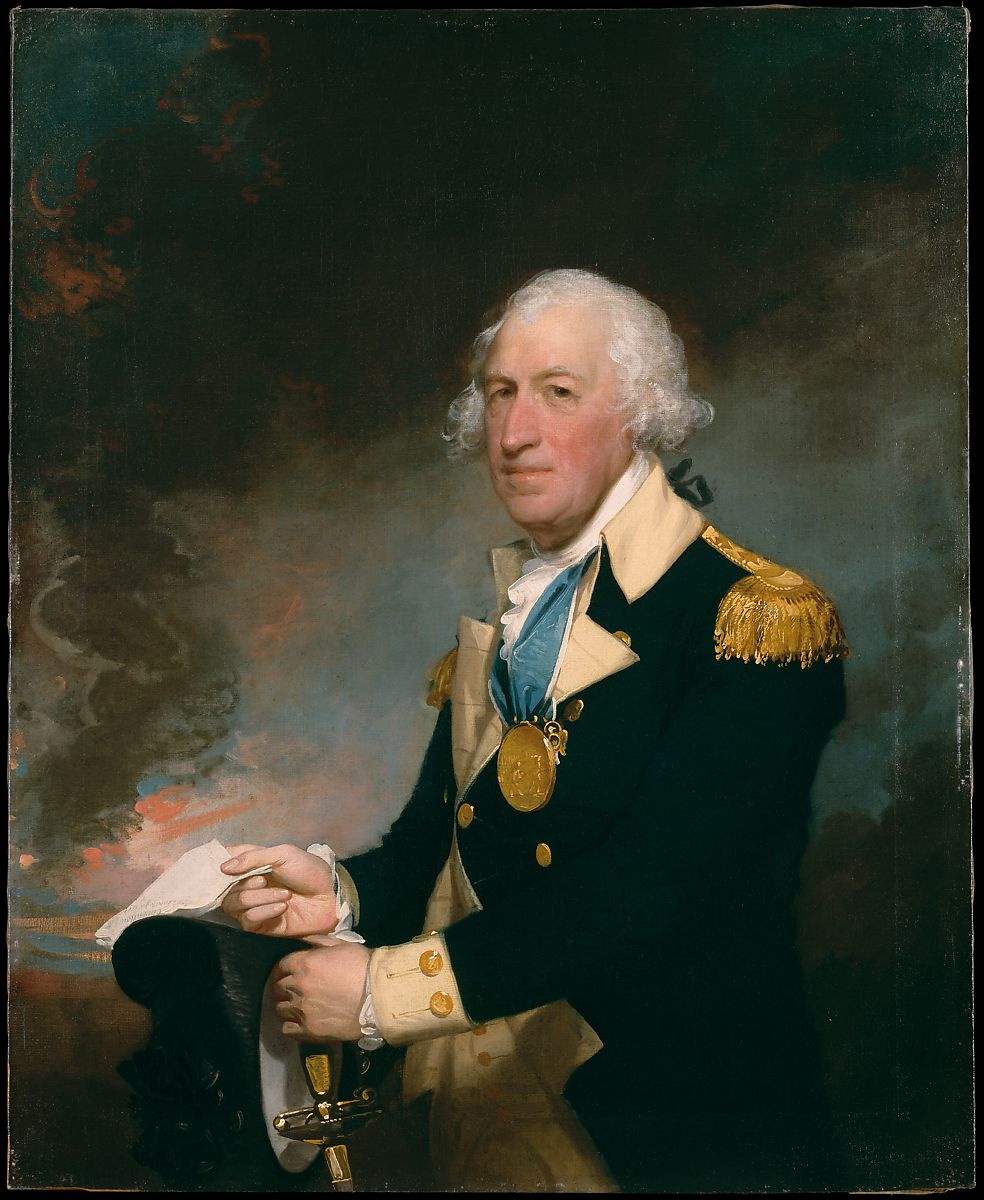

Some 10,000 soldiers, the bulk of the Continental Army, stood duty in the region known as the Hudson Highlands, a strategically vital area overlooking the spot where the river narrowed. Most of the men lived in log huts constructed in the farmland to the west of New Windsor, nestled among places with such appealing names as Snake Hill and Murderers Creek. A dozen miles south, a garrison guarded the fort at West Point, while other units were scattered another dozen miles beyond at Stony Point and Verplanck's Point. The commander in chief, General George Washington, was headquartered in a Dutch-style stone house along the river in Newburgh, two miles north from the main body of his men. The American victory at Yorktown in October 1781 had bloodied the enemy and driven the British ministry to the bargaining table, but British forces in North America remained formidable, above all in New York City. If the British decided to renew the war and resurrect their old strategy of dividing the colonies along the Hudson, the American army was nearby.

The Highlands was also a place of sylvan solitude, conducive to contemplating life, and as the days slipped by and the drudgery of winter quarters dragged on for the eighth time in the war, the officers' thoughts turned to all they had sacrificed and the scant rewards they had enjoyed for it.

For eight years, the army was paid sporadically, and when it was, compensation was delivered in a mess of notes, certificates, and cash that had so depreciated that it was nearly worthless. In the wake of mass resignations and the treachery of Benedict Arnold in 1780, the officers had forced Congress to promise them pensions, but the treasury was empty--worse than empty: the nation was deeply in debt and the only way out, new taxes, was deeply unpopular. When the officers looked outside their ranks, they saw greedy civilians snug by their firesides. Civilian government employees were paid reliably, while soldiers hunkered down in the snow. The officers believed in the cause. They believed in independence. They believed in republican government and creating the world anew. But they also saw themselves as gentlemen, and gentlemen needed to live a certain lifestyle, surrounded by certain fine things, to display their status. For the men with families, serving during the prime of life had taken away their chance to earn a genteel living and impoverished those who depended on them. For younger men, devotion to the army had delayed family formation and the entrance into full adulthood. An officer’s title might help their prospects, but if a captain, major, or colonel proved to be penniless who would want him?

The officers felt ignored and even suspected. Many civilians looked askance at them--and felt justified in their misgivings. The army were liberators, yes, but the republican ideology of the 18th-century Anglo-American world taught that a professional army was a favorite tool of the tyrant. Pensions were another. Pensions preferred some men to others, and made them dependent on government largesse taken by taxing the virtuous. Marry the two, and for many Americans, alarm bells sounded.

None of the officers' complaints were new. Earlier in the revolution, the urgency of the war had overcome the worst of the mutual suspicions harbored by soldiers and citizens. But as 1782 turned to 1783, treaty negotiations, long stalled by British domestic politics and the entanglements of the Franco-American alliance, moved forward. It was only a matter of time before peace was brokered and the people decided to break up the army, with or without a final financial settlement. Sensing time was not on their side, in December 1782 the officers sent a delegation to Philadelphia with a memorial to Congress documenting their hardships and asking for a speedy resolution to their claims for justice. As the delegation lobbied Congress in January and February 1783, they sent news back to the army with a taste of encouragement most congressmen were sympathetic to the army's plight - mixed with a heaping lump of delays, obfuscations, and the excuses that had long embittered Congress's relationship with the army.

By March, patience wore thin. When the anonymous letter appeared, the officers passed it around, distracted from the morning routine by its flashing rhetoric. The letter's author, whoever he might be, knifed into each of the officers' sore points. Announcing himself "a fellow soldier whose interests and affections bind him strongly to you," the anonymous author declared himself disabused of his faith in Congress. Nothing would come from their memorial. It was naive to expect otherwise. He saluted his fellow officers as the deliverers of the republic. "Yes, my friends, that suffering Courage of yours, was active once, it has conducted the United States of America, thro' a doubtful and a bloody war," he wrote. "It has placed her in the Chair of Independency." But to what end? For the benefit of the country and its people? "Or is it rather a Country that tramples upon your rights, disdains your Cries-&insults your distresses?"

Though unknown at the time, the letter was the work of Major John Armstrong, Jr., a twenty-four-year-old aide-de-camp to General Horatio Gates, a one-time rival to Washington who'd once hoped to parlay his victory at the Battle of Saratoga into overall command of the war. Armstrong was one of several young staff officers living at a New Windsor house that served as Gates's headquarters, and together with his friends, he composed the letter on the night of March 9 and prepared copies for distribution. Warming to his theme, Armstrong raised a vital question: what should the officers do? Send a new message to Congress, he answered, no longer asking but demanding, and making clear the consequences of more delays. "Carry your appeal from the Justice to the fears of government," he implored. "Change the Milk & Water stile of your last Memorial-assume a bolder Tone, decent, but lively, spirited, and determined." By meeting the following day, they could choose "two or three Men, who can feel as well as write" to tell their civilian leaders that this was their last chance, that "the slightest mark of indignity from Congress now, must operate like the Grave, and part you forever." Armstrong concluded by reminding the officers of their options. If peace came, they didn't have to comply. They could refuse to disband.

If the war continued, they didn't have to fight. They could leave the country to fend for itself. When news of the letter reached General Washington in Newburgh, he projected calm firmness. In the next day's general orders, he forbade the officers from meeting that day. "His duty as well as the reputation and true interests of the Army requires his disapprobation of such disorderly proceedings," the orders read. Perceiving that clamping down too hard might cause a worse outburst, the general diffused the pressure by rescheduling the meeting. Washington set the time and place--"12 o'clock on Saturday next at the Newbuilding," a newly constructed social and meeting hall in New Windsor often styled "The Temple."

Washington also set the agenda. "After mature deliberation," he directed, "they will devise what further measures ought to be adopted as most rational and best calculated to attain the just and important object in view," meaning Congress's handling of their grievances, and "report the result of the Deliberations to the Commander in Chief," indicating he would not attend.

At headquarters, surrounded by his staff, or "military family" as he liked to call them, Washington was vexed by the anonymous letter. He knew the mood in camp could be surly because he knew the privations that were part of life in the Continental Army. He knew that men marched in worn out shoes and in threadbare clothes, hardly cutting the elegant figure he demanded. He knew that the states, the locus of power in the nation, put their own interests first and that a hamstrung Congress could not equip the army efficiently. He knew that cunning suppliers sent rancid beef and foul whiskey and charged sky-high prices because inflation was through the roof and the nation's credit had cratered long before. By any measure, Washington was a wealthy man, but even he felt the pressures of a thin wallet, his farms never meeting expectations in his absence. He ate better than others and dressed better than others, but, fatigued by constant paperwork and bearing the burden of ultimate command, he knew the physical, mental, and emotional toll taken by the war. But he never thought the army was in crisis until now. Washington was not at his best in the heat of the moment. On the battlefield, he could be hesitant when boldness was needed, and impulsive when the occasion called for restraint. Even in his larger conduct of the war, Washington fixated on some objectives--he was obsessed with attacking New York City--only to be dissuaded by his officers and allies.

Washington's true talents as a general were his organizational abilities, relentless attention to detail in administration, and deft sense of the war's politics, skills he learned as a Virginia gentleman planter-politician. Washington's true genius as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in the American Revolution lay in his rock-solid commitment to the ideals of the cause, his unwavering deference to civilian authority, and his unshakeable belief that the Revolution would succeed. He was the right man, in the right place, at the right time, for the kind of war that the Americans fought.

As the week wore on and Washington kept up the appearance of boring camp life, he worked to confront the officers' anger head-on. Consulting his staff and trusted advisers, Washington prepared to take the unhappy officers by surprise. He would address them as a group--the first time he would do so, at that late date in the war. His words, carefully chosen, would call them back from the precipice.

As it turned out, words weren't enough. The events of that week in March 1783 marked the culmination of what is often called the Newburgh Conspiracy, a mysterious episode in which nationalist-minded leaders in Philadelphia such as Super-intendent of Finance Robert Morris, his assistant (but not relative) Gouverneur Morris, Congressman Alexander Hamilton, and others supposedly combined with disgruntled officers led by General Gates to pressure Congress and the states to approve new taxes and strengthen the central government--and maybe even replace Washington in command.

The label "conspiracy" poses a problem, however. It prejudges the event's core question: Was there really a plot between Philadelphia nationalists and angry officers to achieve their political goals with the threat--or reality--of violence?

People in the 18th century loved conspiracy thinking; for them it was inconceivable that events unfolded by anything other than design. People today also love conspiracy theories, with varying degrees of devotion. They can be a fun source of debate, or a debilitating pathology for individuals and whole societies. Regardless of whether it was a conspiracy, the events at Newburgh represented a pivotal moment at the end of the American Revolution that exposed the tensions between the states and the central government and between the army and civilians that had simmered throughout the war. In the two years from the October 1781 victory at Yorktown, often thought to have ended the war, and the official announcement in America of the Treaty of Paris in November 1783, the prospect of peace actually made the tensions among Americans worse as the logic for hanging together--fighting the war so they would not all hang separately as rebels--dissipated and the nation was left to decide what the Revolution was for.

It was a crisis of peace, a time when the Revolution still might have failed, and the crisis at Newburgh was an hour of grave danger.