Overshadowed in memory by Lexington and Concord, the Massachusetts town of Menotomy saw the most violent and deadly fighting on April 19, 1775.

-

Spring 2025

Volume70Issue2

Editor's Note: Michael Ruderman is an author who frequently lectures on New England history to community groups and historical societies. He earned a degree in history at Harvard College.

It was planned as a simple expedition to Concord “to arrest and imprison the principal actors & abettors in the Provincial Congress.” But the raid became a day-long running battle as nearly four thousand Colonial troops from across eastern Massachusetts confronted 1,700 Royal infantry and marines retreating back to Boston.

What transpired in the town of Menotomy along the way shocked participants on both sides of the fighting. Today the name of Menotomy is little remembered outside its location in Arlington, Massachusetts. It appears as a footnote, if cited at all, in standard histories of the American Revolution. Most modern studies focus on the outbreak of the war itself and give it just a few paragraphs. There isn’t a Menotomy town green or common to visit today; technically, Menotomy’s common was four miles to the east, in the heart of its mother town of Cambridge.

Eighteenth century Menotomy was a village of four to five hundred farmers, millers, tavern keepers and their families. It grew up along the Concord road (now Massachusetts Avenue) from high ground known as “the foot of the rocks” in the west near Lexington, to Cambridge and Charlestown in the east. The town was incorporated in 1807 as West Cambridge, losing its original Indian name, and renamed as Arlington sixty years later.

The Concord road through Menotomy follows the course of Mill Brook for about three miles. Its swift flow is powered by a fall of 150 feet in that short distance. European colonists established nine separate mill sites along the brook, beginning with Captain George Cooke’s grist mill in 1638. They built and improved roads from these mills to their markets in all the neighboring towns, and taverns served the travelers to and from the mills.

Thus in Colonial times Menotomy was an important hub for local farmers. Political leaders knew it as a relatively safe place to exchange information and plan for the coming of war. And spies, especially those serving the Royal Governor, General Thomas Gage, scouted its highways for avenues to enforce royal authority. The roads radiating out in many directions would prove vital for messengers riding out, and militia companies coming in to defend the colony.

Military action began on the night of April 18th. Earlier that day the Provincial Committees of Safety and of Supplies met in Menotomy in Ethan Wetherby’s tavern known as the Black Horse. They had been meeting jointly throughout the winter for a shared purpose: procure and distribute weapons, munitions and rations for the defense of the Massachusetts Bay Colony from General Gage’s 4,000-strong garrison. The diary of their discussions that day records details both mundane and foreboding: move the provisions stored in Concord (beef, flour, molasses, candles) further away from Boston; “deposit” 15,000 canteens in various towns; “lodge” one hundred rounds of gunpowder, canister and shot with “each of the twelve field pieces belonging to the province…”.

The Committees trusted in the revolutionary sentiments of the people of Menotomy for their security from royal interference. Hadn’t their minister, Reverend Samuel Cooke, just last month preached a sermon on Nehemiah’s exhortations to the defenders of Jerusalem: “Be ye not afraid…remember the Lord…fight for your brethren, your sons, and your daughters, your wives, and your houses.”?

The Committees felt safe enough in Menotomy that when they adjourned on the 18th, they voted to meet again in the same place the next day. Three Committeemen from Marblehead – Jeremiah Lee, Elbridge Gerry and Azor Orne – decided to lodge overnight at the Black Horse, their homes being almost 20 miles distant. That sense of safety was shattered sometime after 3:00 AM. The expeditionary force of 800 Royal troops under the command of Lt. Col. Francis Smith came marching up the Concord road, and a detachment pounded on the tavern door and demanded entry. The Marbleheaders eluded capture and interrogation by leaping out the back windows, dressed only in their nightclothes, and hiding themselves in a chilly field of corn stubble for an hour.

Was Smith acting on a guess, or intelligence? He had no orders to stop in Menotomy or anywhere else, only “March with a Corps of Grenadiers and Light Infantry…with the utmost Secrecy to Concord, where you will seize and destroy (sic) all Artillery, Ammunition, Provisions, Tents, Small Arms, and all Military Stores whatever…” Smith must have had a good reason to search the Black Horse tavern. He was perilously behind schedule already, if he hoped to catch the colonials’ s stores by surprise. There hadn’t been enough longboats to ferry the troops from Boston in one movement, and they had to slog their way ashore through the marshes on the sea side of Phips’s farm in Cambridge. Then they halted “till 2 oclock in the morning waiting for provisions” according to the diary of Lt. John Barker of the 4th Regiment of Foot (“which most of the Men threw away, having carried some with ‘em”).

Indeed, Paul Revere had beaten Smith to Menotomy by three hours, stopping there to warn their minute men’s Captain Benjamin Locke on his ride to Lexington. Smith’s men heard, as they left the Black Horse, the sounds of guns and church bells. All secrecy was lost; the countryside was alarmed to their presence.

Smith dispatched a post rider to Boston with an urgent request for reinforcements and continued his march towards Lexington. Most Menotomy families sent their women and children to seek refuge in homes far removed from the Concord road. Benjamin Locke mustered the Menotomy minute company before dawn, as five dozen colonial captains in surrounding towns were now doing, and set off in pursuit of Smith.

Around 9:00 that morning, Lord Earl Percy marched from Boston with a thousand more “Regulars” to rescue Smith. He also brought supply wagons, heavy with gun powder and shot, and two field pieces (six pounder cannons). Taking the land route—Boston neck, to the “Brighton” Bridge over the Charles River and to Harvard College in Cambridge (where he needed to ask an errant tutor for directions), Percy reached Menotomy at midday and found “all the houses were shut up, and there was not the Appearance of a Single Inhabitant…”

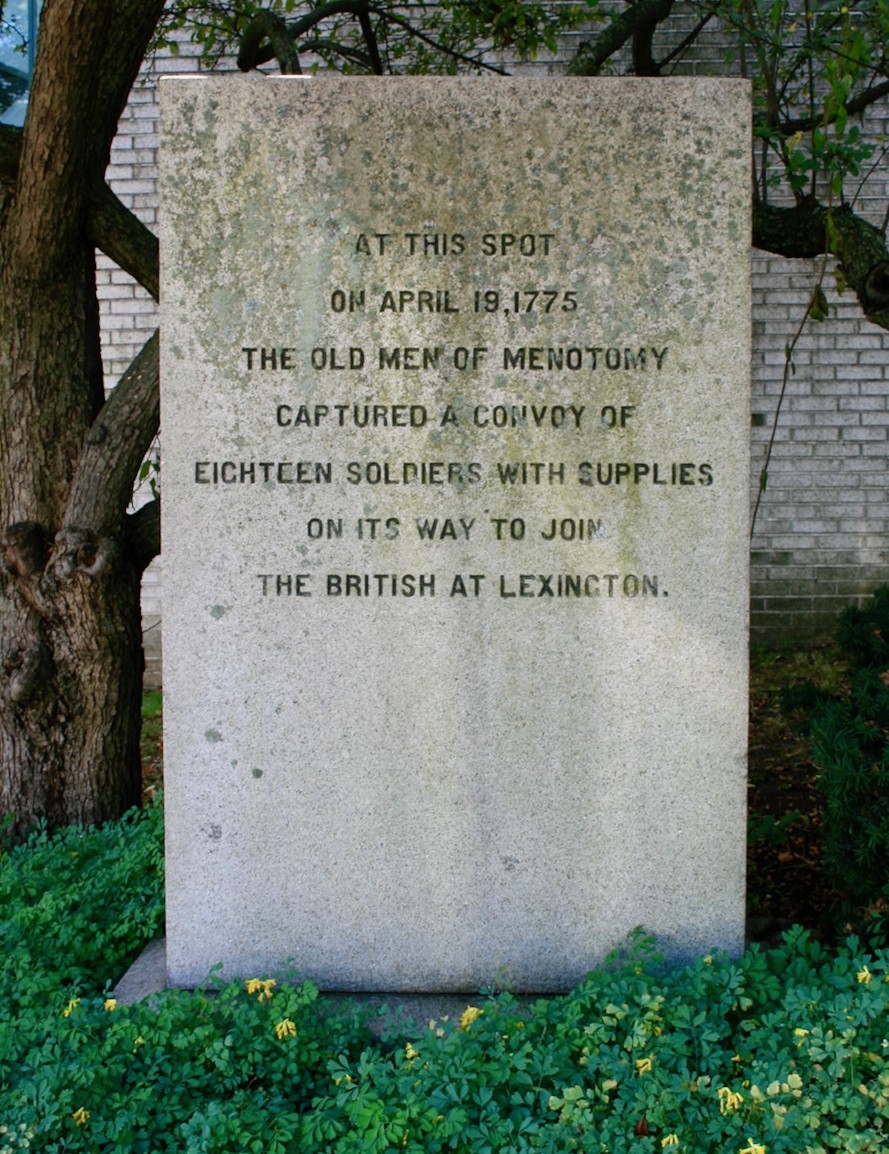

Appearances were deceiving. About a dozen older men had secreted themselves in Cooper’s Tavern. They had information, carried by a colonial express rider almost on Percy’s heels, that a convoy of supply wagons had been unable to match the pace of the main company of Regulars, and had fallen behind the van. The Menotomy men planned an ambush to be led by David Lamson, a mulatto, who had served in the French and Indian War.

“Lamson ordered his men to rise and aim directly at the horses, and called out to them to surrender,” Arlington minister Rev. Samuel Smith wrote in 1864. “No reply was made, but the drivers whipped up their team. Lamson’s men then fired, killing several of the horses, and, according to some accounts, killing two of the men and wounding others... The frightened drivers leaped from their places, and with the guards, ran directly to the shore of Spy Pond, into which they threw their guns.”

By the time of the supply wagon ambush, 35 fresh companies of minutemen from other towns were taking up positions in Menotomy. The Medford, Malden and Watertown companies came from the nearest the village and arrived first. Norfolk, Dedham, Roxbury and Brookline men lined the “Battle Road” on the south, some of them marching twelve miles to get there. The “Essex (County) Men” (from Lynn and Salem, including today’s towns of Danvers, Beverly and Peabody) had come from the north and northeast. Some of them had traveled an astonishing 16 miles in only four hours, each man carrying a standard kit (musket, powder and shot, bladed weapon and canteen) weighing approximately 25 pounds. Percy was caught between the 2,000 colonial soldiers who had been chasing Smith’s retreat from Concord and Lexington, and 2,000 more along his only route of escape to Boston.

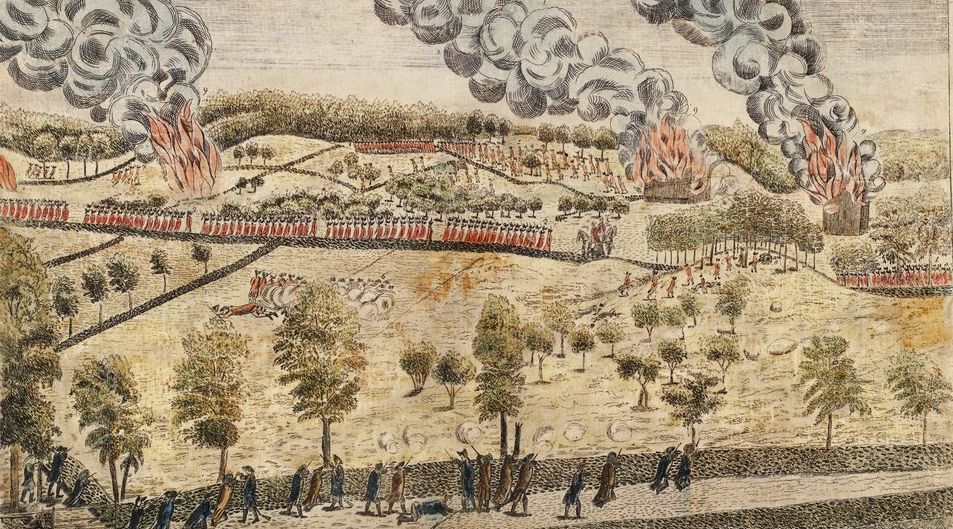

The fighting was savage. Percy needed his cannon repeatedly to keep the road ahead clear of gathering militia. British flanking soldiers attacked house after house, desperate to suppress the colonials’ attack. An infantryman wrote in his diary “hot fire from all sides…every wall lined, and every house filled with wretches, who never dared show their faces.” Royal Governor Thomas Gage called it, in his report to London, “a moving circle of fire” that “continued without intermission.” A fusilier wrote in his diary “We were obliged to force almost every house…all that were found in the houses were put to death.”

One of these houses belonged to Jason Russell. Fifty-nine years old and commonly described as lame, Russell had wisely decided to seek shelter. He led his wife and youngest children safely up the hill to the ridge behind his house. But then he stopped and returned, “to look after things at home” (according to Rev. Smith). Russell fashioned a redoubt of sorts from bundles of shingles in his yard and waited for the regulars.

Their redoubt was no obstacle for the flankers who Percy had set out on either side of his column. Russell and the Essex men who had joined him were surrounded. They all dashed for the house; a few reached the basement, turned their muskets around and killed the first regular who followed them down the stairs. The rest of the colonials were slaughtered, shot and bayonetted outside and inside the house. Russell’s neighbor Ammi Cutler long told the story that Jason was killed “on his doorstep.” Late that day, Russell’s wife Elizabeth returned to find her husband and the bodies of eleven other colonials laid out on her kitchen floor, a floor which she remembered as being “ankle deep with blood.”

A little further down the road from Russell’s, Samuel Whittemore fared a little better. Eighty years old, Whittemore had left his home and taken a position behind a stone wall in the village center. With pistols, muskets and saber, Whittemore mounted a solo attack and killed three of the retreating infantry. He was “shot, bayonetted and left for dead; but recovered and lived to be 98 years of age.” So says his 1793 obituary, which was reprinted in newspapers throughout the new nation.

The horrors of war were felt within the home of Rachel and Benjamin Cooper. They kept a tavern at the corner of the Medford road where Paul Revere made his turn for Lexington, and “The Old Men” had planned their ambush. We have the Coopers’ own words for what they experienced, from an affidavit given at the request of the Provincial Congress:

“…the King’s regular troops, under the command of General Gage, upon their return from blood and slaughter which they had made at Lexington and Concord, fired more than an [sic] hundred bullets into the house where we dwell, through doors, windows, &c. then a number of them entered the house, where we and two aged gentlemen were, all unarmed, we escaped for our lives into the cellar, the two aged gentlemen were immediately most barbarously and inhumanly murdered by them, being stabbed through in many places, their heads mauled, skulls broke, and their brains out on the floor…”

Hannah Adams thought she would suffer a similar fate. Her husband Joseph, fearing the royal troops had marked him (as Deacon of the First Parish Church and a leader in the town) for capture, had spent the day hiding. Hannah was still on bed rest after delivering their daughter Ann less than three weeks before. The regulars forced the house, and Hannah’s deposition says “…One of said soldiers immediately opened my [bed] curtains with his bayonet fixed, pointing the same to my breast. I immediately cried out for the Lord’s sake do not kill me…” She escaped with nothing but a blanket to cover both her and her daughter while the soldiers tried to set fire to the house. (The older children extinguished the fire with water and beer).

It took Percy with his combined command almost five hours to fight his way out of Menotomy, a distance of only three miles. He lost 40 men, more than half of his day’s 60 to 80 men killed. Similarly, the colonial units counted 25 of their 49 men dead in Menotomy alone.

So what is the significance of the Battle of Menotomy, fought in a small village on the edge of a global empire, on the first day of eight years of revolutionary war? At a minimum, it completes the military history of that first day. It was a day that was spectacularly bad for General Gage’s troops. His officers had grievously underestimated the resolve of the colonials. Every report, every dispatch sent back to London was full of the stories of the combined militias’ ferocious bravery. There would never be an easy solution, even by force of arms, to the unrest in the Province of Massachusetts Bay.

The second lesson would be the stories gathered in Boston and printed and published throughout the colonies: General Gates’ troops savagely murdering innocent farmers, committing barbarous atrocities and pillaging the homes of Englishmen. It was a message of rebellion carried from New England to all the colonies: join us, or die. The same message, as assembled by the affidavits collected by the Provincial Congress, was transmitted to the London press on the fastest ship the colonials could hire. It became the only topic of political discourse in the city for 10 days until Gage’s official account arrived.

Finally, we look to the fate of the militia themselves. After joining in battle in Menotomy, they broke with all precedent for minute companies responding to previous alarms. Instead of returning home, they stayed in the field. They occupied the heights surrounding Boston and effected a blockade of Gage and his garrison.

Within five days of the battle, John Adams had the news in Philadelphia. He was representing Massachusetts in the second Continental Congress. With the reality of “an army in the field”, Adams could work on convincing his fellow delegates that there could be no more entreaties for peace. On June 14, he wrote in his diary of the deliberations of the day, “I concluded with a Motion in form that Congress would Adopt the Army at Cambridge and appoint a General…” The motion carried.

The next day, Adams ensured the “Army at Cambridge” would not be simply a Massachusetts army, or a New England army. He proposed to put a southerner, a Virginian at its head. In doing so Adams, risked his reputation with John Hancock of Massachusetts, who saw himself as the logical Commander in Chief. In Adams diary for June 15: “…Mr. Hancock, who was our (Congress’s) President, which gave me an Opportunity to observed his Countenance, while I was speaking… “… when I came to describe Washington for the Commander, I never remarked a more sudden and sinking Change of Countenance. Mortification and resentment were expressed as forcibly as his Face could exhibit them… …Mr. Samuel Adams Seconded the Motion, and that did not soften the Presidents Phisiognomy at all.”

The colonies now had a Continental Army to enforce enforce a declaration of liberty from Crown rule.