When the two parties gather to select their candidates, the proceedings will be empty glitz, with none of the import of old-time conventions. Or will they?

-

July/August 2000

Volume51Issue4

At some point in this election-year summer, as thousands of politicians, delegates, and journalists gather for the quadrennial rites of democracy known as national political conventions, commentators will complain that the proceedings have devolved to nothing more than a long television commercial. And, after invoking images from the innocent past, when sweaty men in baggy suits waving smelly cigars decided grave matters of national import, they will announce that they’ll no longer pay no attention to these political anachronisms. Some will take their cue from Ted Koppel, the host of ABC’s “Nightline,” who left the Republican convention in 1996 in a huff, saying he would not allow his show to be party to a political advertisement.

Like sports fans who watch replays of old championship games, many politics watchers long for an era when everything seemed more authentic and pure. They yearn for those conventions that featured spontaneous demonstrations, soaring speeches, dramatic debates, and heroic candidates. Their folk memories of the golden age of political conventions are preserved in black-and-white newsreel footage starring the great names of the past—Al Smith, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Robert Taft, Tom Dewey, Wendell Willkie—as they thrashed out great issues in full view of the press, when a single great speech could result in a stampede and change the course of a campaign. Again, like nostalgic sports fans, they insist that today’s conventions, with their Hollywood-style packaging, have been corrupted by modern values and well-tailored political consultants who worship the false gods of image and advertising.

There is some merit in these complaints. Indeed there was merit in them when they were first made—more than a hundred years ago. In the early 1890s, Theodore Roosevelt complained that the legendary political operative Mark Hanna was selling his choice for the 1896 Republican nomination, William McKinley, “as if he were a patent medicine.” (And a fine salesman Hanna was; Roosevelt availed himself of McKinley’s medicinal qualities in 1900 by becoming his vice president and then succeeded to the White House when McKinley died of an assassin’s bullet in 1901.)

Those who believe that television, polls, consultants, and the primary system have robbed the conventions of any spontaneity might be surprised to learn that seventy-five years ago their counterparts were lamenting the intrusion of radio coverage, which had begun at the infamous 103-ballot Democratic National Convention in 1924. Talk about a loss of spontaneity. When an exhausted Alben Barkley, acting as chairman, tried to restore order during the vice-presidential nominating process, he turned to the raucous New York delegation and shouted, “Dammit, can’t you wait?” A mild enough epithet by today’s standards, it caused a scandal when the phrase made its way over the innocent airwaves of Prohibition-era America. Suffice it to say that from then on, convention chairmen have taken great pains to avoid such a display of authentic, spontaneous emotion.

Likewise, today’s critics might be surprised to discover that in 1952, when primaries were truly beginning to overtake the old-time bosses, the Democrats’ convention chairman, Sam Rayburn, instructed the delegates to make sure their balloons didn’t get in the way of the television cameras. And that was long before conventions began adopting production values rivaling those of the Academy Awards shows. Still, there’s no denying that these gatherings aren’t what they used to be. Political conventions have been stripped of much of their former drama and chaos and now are as well scripted as any self-respecting professional wrestling match.

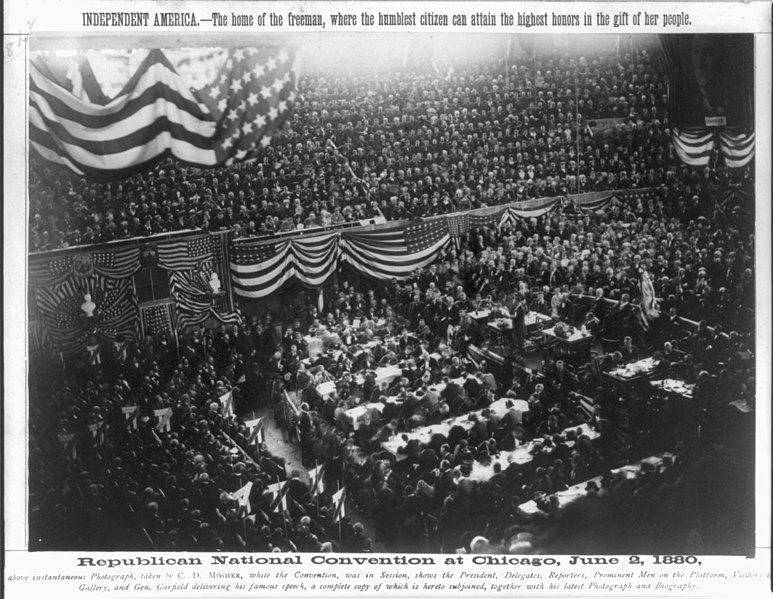

Back in another time, before television and primaries, conventions were part of the American political iconography, and almost every American had a mental image of what one ought to look like: halls bedecked with flags, sober speakers delivering staccato speeches in front of giant microphones, jubilant delegates marching through the aisles, partisans with buttons and signs and balloons. Today the convention might as well take place in a television studio. Every rhetorical body slam, every seemingly spontaneous poke in the eye, has been tested and rehearsed. Speakers are selected with the TV camera in mind, and their speeches are written for TV attention spans. Any semblance of dissent is dealt with long before the opening gavel sounds. Tom Hayden, the California state senator, who in 1968 was on the barricades outside the raucous Democratic National Convention, complains with good reason that today’s politicians regard conventions “as the perfect commercial, because it looks something like the truth.”

Blame it on television. Blame it on the proliferation of primaries. Blame it on the general decline of politics into just another branch of entertainment. Blame it on the media, which want to crown a nominee after the New Hampshire primary. And, by all means, blame it on Franklin Roosevelt, who may have done more to ruin convention drama than television and the primaries put together: In 1936, he successfully pushed to abolish his party’s requirement that a nominee have the votes of two-thirds of the delegates. Thereafter, it took only a simple majority, which ensured that there would never again be a wearying debacle like the 1924 one in New York, which lasted 16 days.

All these developments have conspired to take the old-fashioned drama out of conventions, to drain the humanity from the proceedings and show us politicians as polished and coifed as network anchors. So if conventions no longer seem to serve the purpose they once did, why bother? They are expensive to put on, they merely ratify what primary voters already have decided, and in a distinctly nonpolitical, apathetic age, they are so, well, political.

A quarter-century ago, Walter Cronkite could call conventions and the networks’ gavel-to-gavel coverage of them a national civics lesson. Now, with no burning issues in the land, the networks are content to limit their coverage to a few speeches, and the very idea that conventions can serve as a civics lesson seems quaint. Indeed, ABC will conclude its daily convention coverage this year with the nighttime panel show “Politically Incorrect,” where the one-time civics lesson is reduced to an exercise in postmodern irony, with miscellaneous celebrities playing a role once reserved for sages and experts. The wheelers and dealers are long gone, and with the presidential nomination process wrapped up by mid-March, the late-summer conventions feel like historical leftovers.

That’s too bad, because for all their lack of drama and relevance, they still provide an important function for party activists who regard their delegate credentials as tickets to a slice of history. Moreover, as the veteran political consultant Hank Sheinkopf puts it, “Every four years children get to see adults talking about the political system in a serious way at the conventions. And the rest of the country gets to see their fellow citizens—the delegates—participating in the political system. That’s not unimportant.” More than six thousand Americans will serve as delegates or alternates at the two major-party gatherings this year. Many will be officeholders, from U.S. senators to local township officials, but some will be ordinary party activists who may never get the chance again, who may have waited years for the chance to sit on the convention floor and walk in famous footsteps. The fifteen thousand journalists on hand may confess to professional boredom; the delegates will not.

Moreover, despite the complaints of journalists, conventions still are capable of producing some news. Take just one example from recent years. In 1988, the Republicans met in New Orleans to ratify the nomination of George Bush, who had dispatched his opponents in the early primaries. At first glance the convention appeared to be shaping up to a television-show affair devoid of drama and mystery, intended more for viewers at home than for the delegates in the hall. Yet a deeper look revealed all kinds of minidramas. As he prepared to accept a nomination he had been working for since 1980, Bush was behind in the polls and apparently unable to shed the formidable shadow of the outgoing President, Ronald Reagan. He had yet to decide on a vicepresidential choice, and most observers figured he would pick one from a familiar cast of interchangeable Republican elders. His campaign was also haunted by the fact that no Vice President had been elected to the big office since Martin Van Buren.

Would Bush be able to assert himself as a candidate in his own right? Could he graciously separate himself from Reagan? Whom would he choose for Vice President and what would that tell us about his strategy? Finally, could George Bush—a product of Eastern, Ivy League Republicanism in a party that was tilting south and west—energize the Republican party’s base, which remained skeptical of his intentions?

Everything was riding on the convention. Then, within only three days, Bush managed to stun the nation with his selection of a young, unknown U.S. senator named Dan Quayle as his running mate; he breathed life into his campaign with a single phrase—“Read my lips: No new taxes”—which, ironically enough, proved to be his undoing four years later; and he coined two other phrases that would find their way into lasting everyday currency: “a kinder, gentler nation” and “a thousand points of light.” Not bad for a glorified television commercial.

Indeed, New Orleans in 1988 provided all sorts of small dramas suggesting that conventions hadn’t quite lost their ability to feed the beast of the news cycle. The surprising nomination of Quayle led to a spate of stories about the new candidate’s very mild military record, which in turn enhanced the drama when Quayle made his much-anticipated acceptance speech. (He made a glancing reference to the controversy by saying he was proud to have served in the Indiana National Guard.) Meanwhile, Bush’s call for a “kinder, gentler nation” was interpreted as an almost shocking shot at the Reagan years. Also, in describing the nation’s network of charities, churches, and other voluntary organizations as “points of light,” the candidate anticipated the current debate about making such organizations the main local administrators of social welfare programs. Bush’s speech became the 1988 campaign’s line of demarcation. When he left New Orleans, he never looked back.

Nor were those the only unexpected and memorable public moments in New Orleans. Several hours after Quayle had been announced as Bush’s choice for the vice presidency, the two held a joint news conference in which the young senator tried to administer a New Age hug to the famously undemonstrative Bush. It was a wonderful scene that captured the generation gap, and perhaps other kinds of gaps, between the two. Later that night, keen observers caught sight of Midwestern Republicans, many of them members of the Christian Coalition, strolling wide-eyed along Bourbon Street. What would H. L. Mencken, famous for his colorful convention coverage as well as for his acerbic attitude toward rustic reverence, have made of it all?

Perhaps that’s the problem—not that interesting conventions are in short supply, but that we don’t have any H. L. Menckens to explain them with insight and wit. For there is no denying the link between our impressions of old conventions and the work of people like Mencken, or Norman Mailer, or Red Smith, or Walter Cronkite, who made them seem important as well as dramatic. Journalists who argue that there can be no more drama at our political conventions may be too jaded to take a closer look. After all, anytime you put a few thousand delegates from around the country in the same hall with thousands more journalists, the possibilities for storytelling ought to be obvious. That’s why The New York Times teamed up its then drama critic Frank Rich with its eagleeyed observer Maureen Dowd to cover the 1992 conventions; why Mailer put aside his fiction writing to report on conventions from 1960 to 1972; why Mencken and Smith stood in line for floor passes every four years; and why conventions still draw veterans like Mary McGrory, Jack Germond, and Jules Witcover, as well as all the network anchors.

Given the changes in American society over the last twenty-five years, it is odd that so many political junkies and journalists look back at the old days with such affection and regard the conventions of today as somehow unworthy. The days of the smoke-filled room—the phrase was coined in 1920, when the Republican party elders met out of public view to decide to nominate Warren Harding—may seem colorful, but in fact they were decidedly monochromatic. During the golden age of conventions, candidates were often chosen behind closed doors, but for all the wrong reasons and by a small group of white, middleaged males.

The Harding nomination is a classic case in point. The Republican convention of 1920 was an old-fashioned, dealcutting suspenseful event. The few primaries then in existence had decided nothing. Delegates arrived in June to find Chicago in the midst of a heat wave with temperatures breaking triple digits. Famous names like Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Hiram Johnson, and Robert La Follette were in contention, and several states put up favorite son candidates to hold votes while deals were made. During the first ballot, when the head of the Missouri delegation announced that his state wasn’t ready for the roll call, a voice from the rafters shouted, “Still counting the cash?”

After four ballots a few party bosses, including Senators Henry Cabot Lodge and William Borah, adjourned the convention, assembled in a smoke-filled room, and eventually settled on Harding because he offended nobody and looked like somebody’s idea of a president.

It’s hard to imagine that anyone today—when women, African-Americans, Latinos, Asians, and gays and lesbians are a vital presence in politics and at conventions—would lament the passing of a time when such a male-only, white-only club could dictate to a convention. The old-time bosses like Tom Platt, Roscoe Conkling, and Richard Croker could never get away with their wheeling and dealing in the twenty-first century.

We are, after all, more democratic and more diverse, and today’s conventions reflect those changes.

In fact, for all their modern flaws, conventions still manage to provide sublime and unforgettable moments. Gerald Ford’s narrow firstballot victory over Ronald Reagan in Kansas City in 1976 led to an extraordinary unscripted climax when the nominee called Reagan to the podium, an unprecedented gesture that could be described as brave, foolish, magnanimous, or all three. Reagan gave an off-the-cuff speech about Soviet threats around the world that implicitly criticized the policies of the man who had invited him onstage. As Reagan spoke, the television cameras cut to Henry Kissinger, the architect of those policies, in the gallery, attempting to look impassive, while his wife, Nancy, smoked a cigarette. (Yes, there still was smoke in 1976.) Reagan’s speech had his delegates as well as Ford’s on their feet.

Mario Cuomo’s keynote speech at the 1984 Democratic National Convention in San Francisco will stand the test of time as one of the great convention orations. Had it been given in 1884 rather than 1984, Cuomo could have left San Francisco with the nomination; indeed, many delegates that night concluded that the party was selecting the wrong man. Cuomo stated the case against the popular policies of Ronald Reagan with a conviction and an eloquence that even Republicans admired. That convention also produced the first woman nominee on a major-party national ticket; Walter Mondale and Geraldine Ferraro waving from the podium together was a milestone in American history. Only the terminally jaded could have left San Francisco (or their television sets) complaining about a lack of drama.

At the opposite end of the political spectrum, Pat Buchanan’s speech at the 1992 Republican convention in Houston gave a passionate voice to one side of a cultural split in the party that has been widening to canyon size since President Reagan left office. Whether watching from the hall or the living room, one could easily imagine George Bush’s supporters cringing as Buchanan declared that the nation was engaged in a “cultural war.” Bush, the embattled incumbent, was doing his best to pacify his right wing, but Buchanan’s prime-time address brought the conflict into the open and added to Bush’s wounds. There was also drama outside the hall in Houston, drama as intense as any floor fight during the golden age of conventions, as pro-choice Republicans, including a number of delegates, clashed bitterly with a right-to-life contingent near a Planned Parenthood clinic. Police had to keep the two sides apart. One pro-choice delegate, Tanya Melich, of New York, packed up and left town after being called a baby killer and a murderer. Her experience led the long-time GOP activist to write a book titled The Republican War Against Women.

To be sure, the 1996 national conventions offered very little of this sort of drama, although historians will one day note that in nominating Bob Dole, the Republican party bade farewell—without, it must be said, any ceremony—to the World War II generation. Both 1996 conventions were suspenseless even by modern standards. In that, they were throwbacks of another sort. When the Democrats, or Democratic-Republicans, as they were called, met for their very first nominating convention in 1832, they simply ratified the choice of President Andrew Jackson already made by the various state legislatures’ party caucuses. The first conventions, like today’s, often served only to put a formal stamp of approval on the party’s preference. In the early nineteenth century, legislative caucuses performed the role now played by primaries. The modern convention movement began with the Anti-Masonic party’s gathering in 1831 in Baltimore. When the caucus system started to break down in the 1830s, the major parties adopted the Anti-Masons’ method of gathering party members together, rather than relying on a congressional party caucus, to choose their nominees.

It didn’t take long for conventions to become known as places where colorful battles were fought. In 1868 the out-of-office Democrats met in New York with no clear favorite until a former governor of New York, Horatio Seymour, was named the convention’s president. With no other candidates able to build support, the convention started to fall in love with Seymour on the fourth ballot. Seymour was horrified. Having turned down a chance to run for President in 1860 and already having taken himself out of the running this time, he announced, “I must not be nominated by this Convention, as I could not accept the nomination if tendered….” The party’s top New York bosses then met at Delmonico’s—where else?—and decided that Chief Justice Salmon Chase, who had been added to the ballot earlier, would be the party’s nominee. By the twenty-second ballot, however, it was clear that Chase was running out of steam, and momentum began to shift back to Seymour, whereupon he attempted to rush the podium to nominate Chase. Seymour’s supporters physically blocked him, dragged him out of the hall, and held him hostage while the dealmakers arranged for his nomination. His last words as a non-nominee were directed to a friend. “Pity me,” he said.

This is just the sort of excitement many seem to yearn for: a competitive convention, multiple contenders, multiple ballots, dinners in Delmonico’s to plot strategy, and, finally, an unexpected climax. But as Horatio Seymour himself might have said, is this any way to pick a candidate?

The old conventions may look like fun from the twenty-first century, but the delegates and bosses often couldn’t wait for them to end. Imagine sitting through nominating and seconding speeches for fourteen candidates, as the Republican delegates were forced to do in 1888. Or the fifty-eight seconding speeches for Franklin Roosevelt in 1936. In 1912 Democratic delegates slept in their chairs as the nominating speakers extolled the virtues of their champions literally until dawn. Like farm work, whaling, or combat, the act of choosing a presidential nominee from a dozen or so candidates looks charming, colorful, or glorious only from the safety of the present. In 1904 it took William Jennings Bryan sixteen excruciating hours to present his planks, clause by clause by clause, to the resolutions committee of the Democratic National Convention. He won his points partly because he had more stamina than the committeemen. And few who suffered through Alben Barkley’s two-hour nominating address in 1932 would sympathize with those who lament the short-attention-span speeches of today.

Still, every now and again, some throwback attempts to recapture the days when delegates had the courage and grit to sit through gales of rhetoric. A young governor of Arkansas did his best Barkley imitation as the nominating speaker at the Democratic National Convention in Atlanta in 1988. Bill Clinton almost committed career suicide with his interminable speech, which inspired old-fashioned excitement only with one simple, two-word phrase: “In conclusion….” At least the hall in which Clinton spoke was air-conditioned. Ah, yes, another reason to be glad to be a convention delegate in the year 2000. Imagine all that hot air in a non-climate-controlled auditorium in Chicago, New York, St. Louis, or Baltimore in midsummer.

While there can be no denying that the multiple-ballot pre-primary convention of yore often had drama no modern one can match, the fact is that for every such convention there was at least one of the sort we would recognize today. Al Smith and Herbert Hoover both had their parties’ respective nominations sewed up before the 1928 meetings; the Republican convention of 1924, which put up Calvin Coolidge for a term in his own right, and the Democratic convention of 1936, which picked Franklin Roosevelt for a second term, hardly justified the bar bills turned in by the political press corps. Of the forty-two Democratic conventions since 1832, twenty-nine have finished their work on the first ballot; the Republican convention has gone beyond one ballot only nine times since 1856. So the drama and mystery that we associate with the old-time conventions may be, like so many of our folk memories, more imagined than real anyway.

The delegates in Philadelphia and Los Angeles this year certainly will witness nothing like the scenes leading to Horatio Seymour’s nomination in 1868. There will be no moments like the confrontation between Connecticut’s Senator Abraham Ribicoff and Chicago’s mayor Richard Daley in 1968, when Senator Abe Ribicoff denounced the Chicago Police Department’s “Gestapo” tactics.

Our current conventions are bound to seem tamer than they were when the nation faced such issues as slavery, segregation, and the Vietnam War. On the floor this year there will be only the arguments of politicians appealing for votes in a time of peace and prosperity.

Not very dramatic at first glance. But look closely. What you’ll be watching is democracy in action. Surely, there’s a story there somewhere.