An exhibit of treasures from the largest private collection of political memorabilia recently opened on Long Island.

-

Fall 2024

Volume69Issue4

It all started with a Robert F. Kennedy presidential campaign button.

What grew into the largest private collection of American presidential election memorabilia was the outgrowth of a happenstance visit by 10-year-old Jordan M. Wright to Kennedy’s Manhattan headquarters in 1968.

The button that the volunteers gave to the inquisitive kid was the seed for a collection that decades later would become the nonprofit organization named the Museum of Democracy.

The Queens, New York-based institution without a permanent home owns more than 1.2 million artifacts. They were collected over four decades by Wright, a New York City lawyer and publisher of trade magazines who died in 2008 just as his first major temporary bricks-and-mortar museum was being mounted.

Now, Wright’s son, Austin, 33, is president of the museum, which reached an agreement with Long Island University in 2022 and has begun exhibiting some of the items at its C.W. Post campus in Brookville.

The family, which is still adding to the collection, had already loaned artifacts for temporary exhibits on Long Island and other places around the country. And it’s working on more satellite display sites and ultimately an online museum.

Wright laid out the story of his obsession in a 2008 coffee-table book, Campaigning for President: Memorabilia from the Nation’s Finest Private Collection. The book was recently updated by author Mark Bego and republished by Yorkshire Publishing.

Wright dedicated his book to “my parents, Martin and Faith Wright, who even with their sometimes limited interest in politics, always encouraged my passion for political memorabilia as a record of our nation’s great democracy” and to his children Austin and McKenzie “to study – as history really does repeat itself – and to involve themselves in campaigns and elections which truly do affect their world and their place in it.”

Austin noted that “my grandparents were collectors. They collected African oceanic primitive art. And so they had encouraged him to be a collector.” And the family had a connection to government and politics. “My grandfather did some work for Henry Morgenthau Jr., who was the treasury secretary under FDR.”

Even as a 10-year-old, Wright viewed his free Kennedy button as more than just a shiny collectible. It was an important symbol for how American democracy functioned.

“After school and before going home, I would stop off at the Robert F. Kennedy for President headquarters,” he wrote. “It was the first place I had ever visited where people were talking about the important issues of the day, civil rights, the environment, and the war in Vietnam.”

But he also took advantage of “an added bonus.” He noted that, “every week, there were new buttons that you could have for free. I never missed a week.”

There was also a very special one-time bonus: Wright got to meet Kennedy. “It was probably only a minute that he spent with me, but what an important minute that was! He told me how proud he was to see someone as young as I was helping to make him president. I think if Kennedy had been elected in 1968, the fate of the United States would have been very different – considerably improved.”

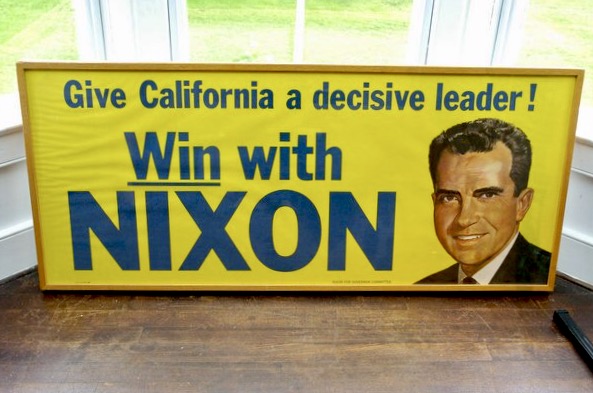

The visits to the Kennedy campaign site led to an epiphany. “It did not take me long to figure out that if they were giving away free buttons at the Kennedy headquarters, then they were probably at McCarthy's, Humphrey’s and Nixon's presidential headquarters, too. There were, of course, also posters, bumper stickers, and campaign brochures. I collected everything that I could get my hands on.”

After visiting the headquarters for all of the 1968 candidates, Wright said, “My next conclusion was that buttons and other political memorabilia could not just have been invented for the 1968 campaign. There had to be prior campaigns that produced this material.”

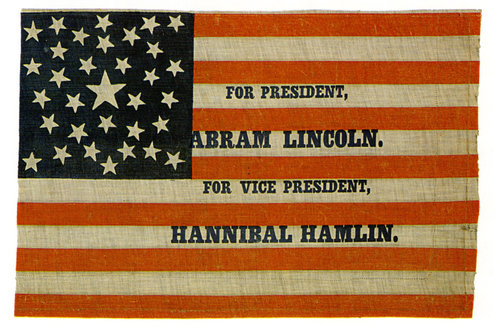

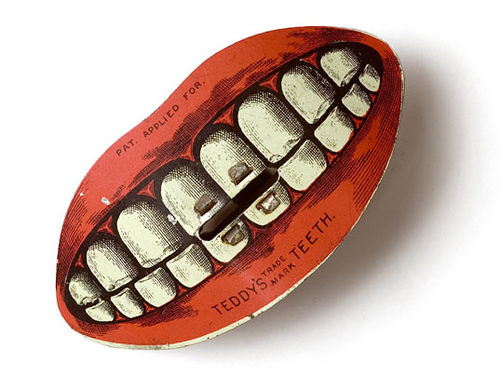

Wright noted in his book that election memorabilia began with the first presidential campaign. “Brass clothing buttons commemorating Washington’s ascension to the presidency were mass-produced,” he wrote. “The chain of thirteen links represents the original states. Many appeared with the slogan ‘Long Live the President.’”

The young collector set out to find artifacts from earlier elections.

While studying at Columbia College in the 1970s, he enjoyed browsing in the cluttered junk shops clustered north of Times Square on Eighth and Ninth Avenues. That’s where he unearthed a one-of-a-kind flag with Washington’s image.

“My favorite was owned by a bickering old couple.… As they argued, I filtered through the junk, and on one visit, I unearthed the Washington flag from beneath a stack of Horatio Alger books. At first they wanted $200 for it, but I convinced them that I could barely afford one hundred. They accepted and I dashed out with a new highlight of my collection.”

Wright said his work often took him upstate to the Finger Lakes region. “One evening,” he wrote, “I stumbled into a firemen’s memorial memorabilia show and sale” where “I found a hand-painted leather James Monroe fireman’s hat for sale, a one-of-a-kind item and a perfect addition to my collection.”

A pair of Ulysses S. Grant and Horace Greeley metal wall-hanging match holders were purchased at a store on the Lower East Side of Manhattan that exclusively sold objects made of metal.

Some items in Wright’s collection found him. “Every once in a while, I get an unexpected call from someone who has heard of my collection and me. Once, an elderly woman called. Her great-grandmother had created a one-of-a-kind folk-art portrait of Abraham Lincoln from seeds and saplings.… When it arrived, it was love at first sight.” Austin Wright said it’s one of his favorite items in the collection.

Wright did not only collect major party candidate artifacts. His source for Communist Party memorabilia was his great-uncle Nat, a lifelong member of the party. “He was always finding memorabilia, or telling me where I could locate posters, leaflets, buttons, and books, all of which eventually ended up in my collection. My favorite comes from one of the best years for the Communist Party, perhaps because of this poster’s strong image: a muscular worker, in red. It is from 1924.”

When Smithsonian Books published his volume in 2008, Wright’s collection consisted of 1.25 million artifacts from the George Washington flag and five buttons celebrating his election up to 4,000 items from the 2004 election.

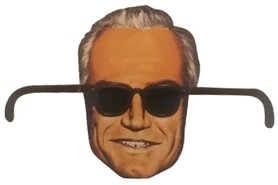

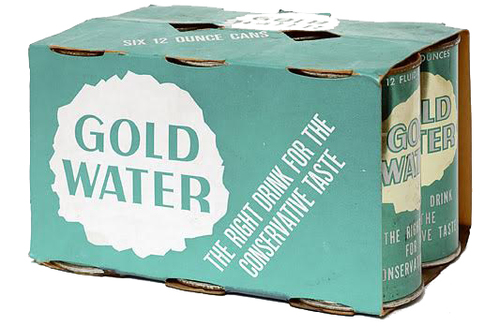

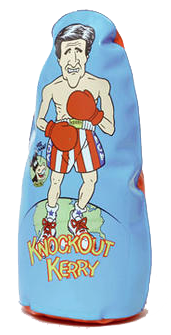

Wright had amassed pins, posters, flags, ballot boxes, canes, hats, liquor bottles, food products such as a 1952 cornflakes box picturing Dwight Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson, paper and metal torches, match books, umbrellas, dolls, china, license plates, record albums from major and third-party candidates and items of politicians running for offices prior to the presidency such as a poster of William McKinley running for governor of Ohio.

Along the way, he acquired “what I believe are near-complete collections … of every African-American, Jewish-American, Asian American and outed-gay candidate for the House, the Senate or governor. My collection of female candidates for governor and senator is near-complete.… I have collections from cabinet members who ran for office, as well as something from each member of both Nixon’s and Clinton’s impeachment committees.

“And finally, as a lifelong New Yorker, I collect everything that is New York: the mayors, governors, senators, Tammany Hall, gentrification, parks, holidays, the Empire State building, the Statue of Liberty, the World Trade Center, and, of course, 9/11.”

Wright admitted that he wasn’t sure what the mission of his collection was. All he knew, he wrote, is that “I like collecting, and even more, I like researching who these characters from the past were.”

Others familiar with the collection have articulated its value.

“It does tell a story of democracy,” commented Brent D. Glass, who served as director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History from 2002 to 2012. “I think that we've become more aware in recent years of just how important political campaigns are in America to preserving democracy, and I think this collection reminds people not just of the colorful aspects and the creative aspects of campaigns, but it really shows the energy and the passion that people have for political campaigns and for democracy. So I think its role is more important now. It’s an extraordinary collection. Very comprehensive.”

Smithsonian curators met with Wright in New York to discuss acquiring his collection but no deal was ever consummated.

“We've had a number of organizations that have approached us,” Wright’s widow Pamela said, “but we believe it's best shown, and if it goes to a museum like the Smithsonian, then 90 percent of it will go into storage.”

Some spouses might have resented Wright’s obsession with collecting and the impact it would have on their home and lives. But Pamela, who met Wright through mutual friends when they both happened to be in California, embraced the collection, in part because she also had politics in her blood.

“I thought it was amazing,” she said. “I grew up in Arizona and I knew Senator Barry Goldwater, who was a friend of my dad. I worked for Senator Goldwater his last two or three years in the Senate right out of college. So, I was very involved politically, and then I worked in the Senate for John Warner. And I went to Georgetown for a master’s degree in American foreign policy. So I found all of it super interesting.”

By the time they got married in 1990, “he had already collected a massive amount of political memorabilia. Together we continued to collect. He loved to collect and categorize, catalogue it and organize it and go to political shows and auctions.”

After the wedding, the couple moved into Wright’s Manhattan loft in Soho filled with political memorabilia and they bought a second loft and connected them into a duplex.

“We knew all kinds of fascinating people and everyone came to see it, politicians and famous people, dignitaries,” she related. “And once the kids came along, Austin had a passion for it even then.”

“Everything was in our apartment,” Austin recalled. “He had countless drawers filled with buttons and different objects.” When he was young, his father encouraged him to show guests the collection. “So, at a very young age, I started to gain an understanding of what the collection was and how to present it and how to talk about it. It became an integral part of my life.”

Even though he enjoyed showing off the collection at his home, in his book Wright admitted to feeling “a bit selfish” because if you did not know him you could never see the artifacts. So a year or two before he died, Wright formed a nonprofit corporation and called it The Museum of Democracy. “Once it finds a permanent home,” he said, “it will allow many more people to see the collection. The Museum of Democracy will not be a stale assortment of arcane campaign buttons but a living, breathing history of the democratic traditions on which we can continue to build.”

“He really wanted to create some museum where he would share it with the world and utilize it to educate kids about democracy and freedom and to inspire them to participate in the political process,” Pamela said.

While the collection has never found a permanent home and probably never will, Wright’s son Austin has come up with other ways to make the objects accessible.

Before his death, Wright and Pamela decided to sell their lofts and move the collection to a warehouse in Queens.

Wright was helping to set up the first major exhibit of his artifacts at the Museum of the City of New York when he died of a ruptured aneurysm in his sleep at the age of 50 a month before the June 2008 opening.

Continuing to run the museum is a full-time job for Austin Wright, who lives in Manhattan with his wife, Madison.

“My family's continued collecting” with several thousand more artifacts acquired since his father’s death.

Acquiring the items has cost millions of dollars but Austin said “I don't like to talk about that.”

He does like to talk about his vision for the museum. “My family has talked extensively about the future of museums, and the future of museums to me is a new-age model. I think there is a component of brick and mortar, but I think there’s a component of the virtual world.”

“We have an entire database online, which is how we keep track of this stuff,” Austin said. But it's not accessible by the public. “My goal eventually would be to create an online institution in the metaverse where you can see every object and the provenance,” he said.

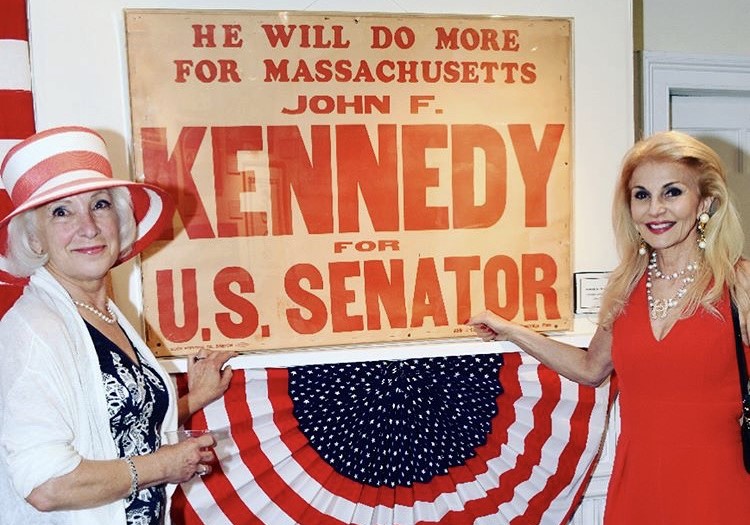

So far, the museum has worked with partners to set up temporary exhibits in Bridgehampton on Long Island, at the Crystal Bridges Museum with the Walton family in Arkansas, at the George W. Bush Presidential Library in Dallas, at the New York Historical Society during the 2016 election campaign focused on the ‘60s and ‘70s, and one on women’s suffrage at the Museum of the City of New York.

The only current exhibit is at the C.W. Post campus of Long Island University. The objects currently on display at the “Hail to the Chief! Electing the American President” exhibit at C.W. Post include a metal parade torch made for John Adams’ campaign in 1796 designed so a lighted candle would burn inside and illuminate his name and the number 1; hand-painted paper lanterns illuminated by candles inside to show support for Abraham Lincoln in 1864 and Ulysses S. Grant in 1872; a metal and glass ballot box from the presidential vote in New Hampshire in 1872 that remains locked and still has ballots inside; and paper dresses with photographs of Richard Nixon and Robert F. Kennedy handed out to young women by campaign organizers in the 1960s.

“We're so grateful for the opportunity to have, in our opinion, the authoritative private legacy of this grand American democracy experiment that started in 1776,” said Andrew Person, co-director of LIU’s Roosevelt School, which also features a White House Experience with mockups of the Oval Office, situation room and press room for use by student groups.

“The uniqueness is that it’s a private collection from George Washington through the present day,” continued Person. “And what it does for the students of all ages that come to Long Island University to witness history is it inspires people to be able to walk in a president’s shoes. It’s important for us to bring this to life for students to not only learn about the past, but be inspired to run for president, particularly women, people of all colors of all ages to run for president. Because if you look at our history, if I was from another planet, or from another country, I would think that the only people that were allowed to be president, the United States were old white guys. But that's our past. That’s not our future.”

Kathryn Curran, executive director of the Long Island-based Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation, was the person who connected the Wright family and LIU and provided a $100,000 grant to create the temporary exhibit.

“The breadth of the collection is staggering,” she said. “It starts with George Washington's button and it moves forward to the last election. It's fascinating because you think that politics are tough today. They were from the beginning. To have it here on Long Island is an incredible plum. And to have it available for students at LIU and faculty and the community. I couldn't ask for a more perfect fit.”

Pamela Wright said, “I think it's just a fantastic partnership and exactly where the collection should be.”

Austin Wright added that “we have to really embrace making sure this is on display and heard, and that young people especially embrace it because the country’s more and more divided and its attention spans are less and less. And I think having something like this can really add value for people in their lives.”

More about the Museum of Democracy: Visiting the exhibit at Long Island University’s C.W. Post Campus is by reservation.

While viewing the artifacts, visitors can also explore the university’s interactive replica of several rooms in the White House.

The White House Experience at Roosevelt House on the campus on Route 25A in Brookville, New York, is the only White House replica in the Northeast and one of four in the United States. It includes life-size replicas of the Oval Office, Situation Room and Press Briefing Room. Visitors can immerse themselves in interactive simulations as they navigate a "crisis" in the roles of president, cabinet members, and reporters.

To arrange a visit, contact WhiteHouseExperience@liu.edu or call 516-299-1242. Website: https://liu.edu/whitehouseexperience.