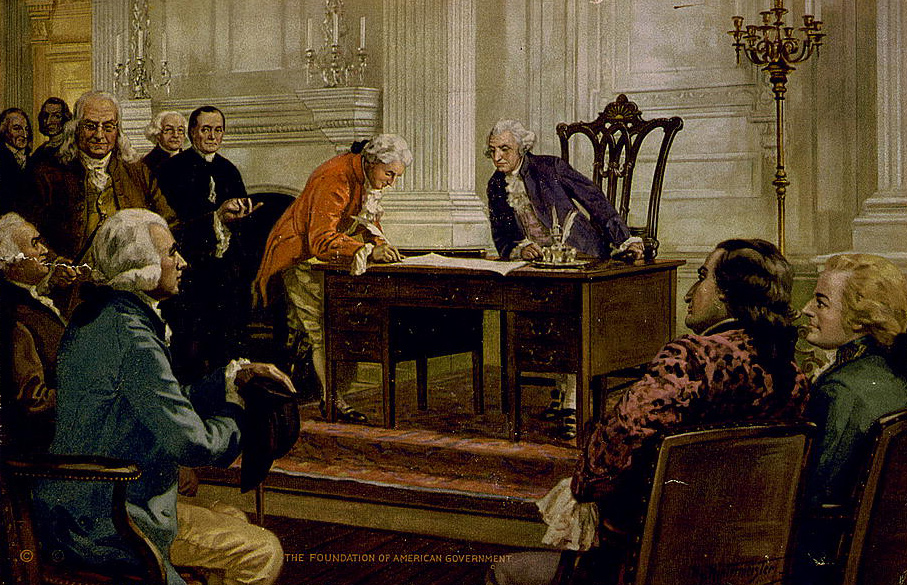

The Constitution is more than a legal code. It is also a framework for union and solidarity.

-

Fall 2024

Volume69Issue4

Editor’s Note: Yuval Levin is the founder and editor of National Affairs and director of Social, Cultural, and Constitutional Studies at the American Enterprise Institute. He writes about the Constitution’s power to unify our fractious nation in his most recent book, American Covenant: How the Constitution Unified Our Nation – and Could Again, from which this essay was adapted.

Hope about our country does not come easily to Americans just now. Our capacity for it has been sorely tested in our time, especially by deepening divisions in our society. Americans have never lost hope in the face of outside threats, but internal discord strikes at the roots of our strength and leaves us doubtful of our capacity for renewal.

In times of division, we tend to equate the sheer multiplicity of American life – the fact that our society is teeming with different people who have different views and form different groups that want different things – with strife and breakdown.

We assume that multiplicity must imply disunity. And, since we know that our multiplicity is a permanent reality, we either rage against reality or grow despondent. This is one reason why our politics now overflows with melodramatic despair.

We have come to see other Americans as problems to be solved and so imagine that the obstacle to unity in our society is the existence of people who do not think as we do. Among other things, this has made us frustrated with our system of government because that system forces us constantly to deal with people who differ from us. Too many Americans are, therefore, persuaded that our Constitution is unsuited to our contemporary circumstances – that it assumes a more unified society than we now have, makes it too difficult to adapt to changing times, and so can only make our problems worse in this divided era.

But the Constitution is not the problem we face. It is more like the solution. It was designed with an exceptionally sophisticated grasp of the nature of political division and diversity, and it aims to create – and not just to occupy – common ground in our society. The problem is that we have forgotten that creating common ground is a key purpose of the Constitution and that it should be a key purpose of our own political and civic action.

We too often lose sight of how the Constitution creates common ground by compelling Americans with different views and priorities to deal with one another – to compete, negotiate, and build coalitions in ways that drag us into common action even (indeed, especially) when we disagree.

This points to an even deeper problem underlying our contemporary frustrations with our system of government: we have not only lost sight of the importance of pursuing greater unity, but we have also tended to forget what unity in our free and dynamic society really involves. Unity doesn’t quite mean agreement. Americans do have some basic principles in common – especially those laid out in the Declaration of Independence. But, although those widely espoused principles impose some moral boundaries on our political life, there is enormous room for disagreement within those boundaries.

This includes some significant disagreement about exactly what the Declaration’s principles actually mean regarding the nature of the human person and the proper organization of society, let alone disagreement about discrete political and policy choices in response to the needs of the day. Our politics is unavoidably organized around these disputes and requires us to take on common problems while continuing to disagree about questions that matter a great deal to us. But that disagreement does not foreclose the possibility of unity.

A more unified society would not always disagree less, but it would disagree better – that is, more constructively and with an eye to how different priorities and goals can be accommodated. That we have lost some of our knack for unity in America does not mean that we have forgotten how to agree but that we have forgotten how to disagree.

The parties to our various disputes now tend to talk about one another more than they talk to one another, and, so, even very active citizens actually spend relatively little time in active disagreement with others, let alone in efforts to overcome such disagreement for the sake of addressing some common problems in practice. This is the sense in which we have forgotten the practical meaning of unity: in the political life of a free society, unity does not mean thinking alike; unity means acting together.

How can we act together when we do not think alike? The United States Constitution is intended, in part, to be an answer to precisely that question. And it is a powerful and well-honed answer. Alleviating the disunity of contemporary America would, therefore, require not recklessly discarding our Constitution as an antiquated relic but rediscovering its fundamental purposes, grasping just how powerfully it speaks to some of our most serious contemporary problems, and finding ways to better put it into practice to address those problems.

That approach involves pushing, plying, and pressuring Americans to engage with one another and so also to understand themselves as engaged in a common enterprise. The Constitution forces insular factions to forge coalitions with others and, thereby, to expand their sense of their own interests and priorities. It forces powerful officeholders to govern through negotiation and competition, rather than through fiat and pronouncement, and, so, to align their ambitions with those of others. It forces Americans to acknowledge the equal rights of fellow citizens, and has (gradually, and thanks to the heroic efforts and sacrifices of many) come to better align the definition of “fellow citizen” with the ideals of the Declaration of Independence.

None of this is easy or simple. All of it happens through politics and so through contention, competition, pressure, and negotiation. It’s a struggle. But the Constitution is rooted in the insight that this very struggle is, itself, a source of solidarity and an engine of cohesion.

We have become too divided in contemporary America, not because we engage in that struggle too intensely but because we avoid it too readily and so have lost some of our knack for disagreeing constructively. The factions in our politics tend to talk about one another rather than to one another, and therefore, we too rarely talk in ways that could point to common action.

Recovering our grasp of why it is important to pursue ways of acting together across differences, and then recovering the habits of doing so, is the path toward a more cohesive society, a more responsive government, and a more responsible citizenry. That grasp could be renewed by coming to know the Constitution again. And those habits could be revitalized by a better practice of constitutionalism.

In sum, the Constitution is more than it seems. We tend to view it as essentially a legal code, a judicial instrument. And the Constitution is a legal framework, to be sure. But it is also an institutional framework; a policymaking framework; a political framework in the highest sense of the political; and, finally, a framework for union and for solidarity.

Although this latter unifying purpose of the Constitution was seen as vital by the framers of the document and was featured prominently in their case for its adoption, it is, for us, the Constitution’s least familiar facet. It is also the one we most urgently need to recover and, for the sake of which, a broader constitutional restoration is essential.