Authentic brass “crickets” issued to American paratroopers on D-Day are now quite rare. A worldwide search recently “unearthed a lost piece of sound history.”

-

Summer 2019

Volume64Issue3

D-Day planners gave American paratroopers an especially difficult assignment — jump out of C-47s into Nazi-held territory just after midnight, capture key bridges, crossroads, and towns, and prevent German counterattacks against Allied forces on the beachheads.

But how could the men, who would be landing in fog and darkness, dispersed by the variables of wind and pilot navigation, identify each other? Gen. Maxwell Taylor, commander of the 101st Airborne, came up with the clever idea of issuing his men little toys that made cricket sounds. A single click on the “clicker clacker” allowed a soldier to ask someone in the dark if they were friend or foe. If the other person responded with two clicks, it was a good bet he was a friend.

In the months leading up to the Allied invasion of Normandy, the 101st Airborne ordered 7,000 clickers from ACME Whistles in Birmingham, England. The clickers were then issued to the paratroopers just before D-Day as a crucial piece of survival equipment.

These “470 Clickers” have become extremely rare. They were used only on the first day of the invasion because the U.S. Airborne Division feared that Nazis would get their hands on some of the clickers, reverse engineer them, and then create their own clickers to lure Allied troops into traps. Soldiers just discarded them after D+1 because they were no longer needed.

Watch John Wayne explain how to use a clicker in the movie "The Longest Day"

Earlier this year ACME Whistles, which was founded in 1870 and still manufactures replicas of the clickers, launched a campaign to try to find one of the little devices in honor of the 75th Anniversary of the Normandy invasion. “We put out a search around the world from Europe to America to try and find an original clicker to ensure this part of D-Day history could be kept,” said Simon Topman, Managing Director of ACME.

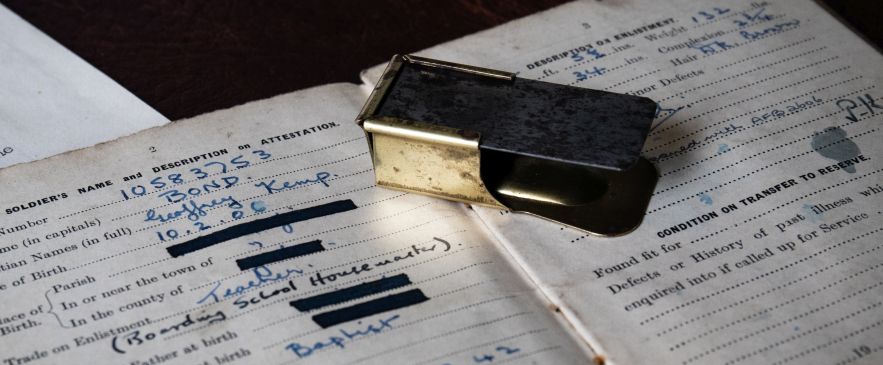

Much to the company’s surprise, an original clicker turned up not far from their factory in Birmingham. Liz Campbell and her husband Diarmid found it among a collection of military items kept by Liz’s father, Captain Geoffrey Kemp Bond (1906 -1997).

Bond, a schoolmaster in Hertfordshire prior to call-up for service, joined the Royal Army Ordnance Corps as a private in the Spring of 1942. Later he received an officer commission and landed at Normandy. In his memoirs he wrote that D-Day was “the biggest jungle of shipping you can imagine.”

By the end of the war Bond was a Captain in charge of a motor transport depot in Twistringen south of Bremen, Germany. His team searched the countryside for equipment and brought it to the depot. After demobilization in 1946, Bond returned to teaching and eventually became a headmaster.

“My father was an avid collector and interested in history,” recalls Liz. Among his collection of stamps and military items, she and her husband found the original ACME clicker, which they gave to the company. “I think the clicker now being displayed back at the factory where it was made would have really put a smile on his face.”

Her husband Diarid Campbell recalls that, “We came across the clicker and realized what it was after we read the news about ACME’s ‘Search for the Lost Clickers,’” which was publicized on the BBC and elsewhere. “We hadn’t realized how rare they were. It’s great to help save this little part of history for others to enjoy.”

“This was the first original that we’ve come across,” says Matt Seabridge, a spokesman for ACME. “They’re extremely rare. Most were just simply discarded during the war and it’s thought that only a very small number of genuine clickers still remain.”

ACME still makes and sells replicas of the clickers, which are popular with reenactors and WWII aficionados. But they have to compete with cheap imitations from Asia. Ironically, if a replica clicker has "U.S." stamped on it, it's not real, since the clickers were an English-made device, and the shape and design are wrong. One Amazon reviewer complained that a fake replica he had purchased “lasted about 5 days before deforming to a point where it could not be bent back and still click. Great for decoration, but I wouldn't recommend using it for an actual purpose.”