Alistair Cooke's new book recalls his tours of war plants and military bases during World War II.

-

August/September 2006

Volume57Issue4

He was, to Americans of a certain age, the urbane, well-bred, well-read, well-connected Englishman who hosted “Omnibus,” a cultural lighthouse that shone over the wasteland of network television in the 1950s. Later, from 1971 to 1992, he presented “Masterpiece Theatre,” the American shop window for the best drama from the BBC.

In Britain, Alistair Cooke was perceived differently. A Lancastrian, born the son of a metalworker in Manchester in 1908, he won a scholarship to Cambridge. In the 1930s he came to Yale as a Harkness Fellow, and for good measure to Harvard as well, ditching his unappealing name of Alfred for a more attractive one. He became the BBC’s film critic and NBC’s London correspondent. His experience in America had shown him his destiny. As European politics withered in the rush to war, he moved permanently to New York, acquiring citizenship in 1941. He remained a continuing presence on British airwaves. His weekly “Letter From America” was broadcast by the BBC for nearly 60 years, ending only weeks before his death, at 95, in March 2004.

Some—including his fiancée, who ended their relationship—questioned his defection to safer shores in Britain’s most perilous hours. In truth, he did wonders for the Allied war effort, interpreting the American character to a British public conditioned hitherto by the likes of Cagney, Bogart, and Shirley Temple. He was as wont to explain the cabals of congressional back rooms as the hardships of an Appalachian miner. He did so with immaculate style, his every sentence an embarkation on a fascinating miniature voyage that would often deliver the rapt listener to an unexpected destination. His voice was smooth, velvety, hypnotic, with an intonation that to Americans sounded patrician British, to Britons that of America’s educated East Coast. His idols of form were H. L. Mencken and Mark Twain, both masters of popular enlightenment through cant-free prose.

As a child, I remember hearing his broadcasts in gray, rationed, bomb-shattered London, describing America in arresting detail. The popular perception, assisted by glimpses of lavish color ads in occasional Life s and Saturday Eve ning Post s for foods not seen in Britain for years, and by the bounty of GIs, far from home, an endless source of Life Savers and Hershey bars for grateful children, was that America, with its unbounded generosity, was a paradise that had escaped the harshness of the war that clamped Europe in its ruthless and inexorable grip.

As a child, I remember hearing his broadcasts in gray, rationed, bomb-shattered London, describing America in arresting detail. The popular perception, assisted by glimpses of lavish color ads in occasional Life s and Saturday Eve ning Post s for foods not seen in Britain for years, and by the bounty of GIs, far from home, an endless source of Life Savers and Hershey bars for grateful children, was that America, with its unbounded generosity, was a paradise that had escaped the harshness of the war that clamped Europe in its ruthless and inexorable grip.

As Cooke realized, it was a misleading, inaccurate conception that even Washington failed to appreciate. He applied for permission to visit war plants and military bases across the nation, intending to talk to hundreds of Americans, from senior administrators to laborers. Rubber was even scarcer than gasoline, but he was granted permission to buy a set of retread tires. Over many weeks he headed south to Florida, then via the Gulf to Texas and the Southwest, up to California and Oregon and over the Rockies to the Midwest, and on to New England.

He found communities whose upheaval was terminal. The little town of Charlestown, Indiana, unrecognizable after the federal installation of a smokeless-powder plant had imported thousands of workers. Deming, a small town in New Mexico where almost all the young men, enlisted together, had vanished when the Japanese overran Bataan. He even gained access to Manzanar, one of several sun-parched desert camps in California where thousands of Japanese-Americans were summarily corralled, leaving homes, businesses, and possessions behind in West Coast cities. “I drove away … none too proud of the showing we had made in running the first compulsory migration of American citizens in American history.”

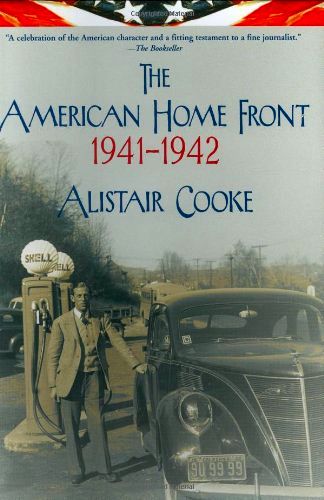

The resulting book was a unique testimony on how the homeland had coped with the most cataclysmic war in history. But with hostilities over, his publisher thought that the public appetite for such an account had vanished. The manuscript was tossed into a closet in Cooke’s Fifth Avenue apartment. Six decades later, just before he died, it was found. Its historical merit leaped from its pages. Although “long past deadline,” as says the veteran newspaperman Harold Evans in his foreword to The American Home Front: 1941– 1942, it nonetheless affirms Cooke’s enduring place as a great 20th-century reporter.

— George Perry