The Jamestown founder is one of those early American heroes about whom historians are apt to lose their tempers

-

October 1958

Volume9Issue6

The origin of the controversy is to be found in the tragedy and misery of the early Virginia years, it was natural that some settlers should try to fix the blame for their misfortunes, and that others should seek credit for the survival of the colony. Among the latter, hardly a single leader made a claim not hotly disputed by his companions, and later generations have taken sides just as dogmatically. Because Smith’s claims were the most startling, they have been the most warmly attacked—and defended.

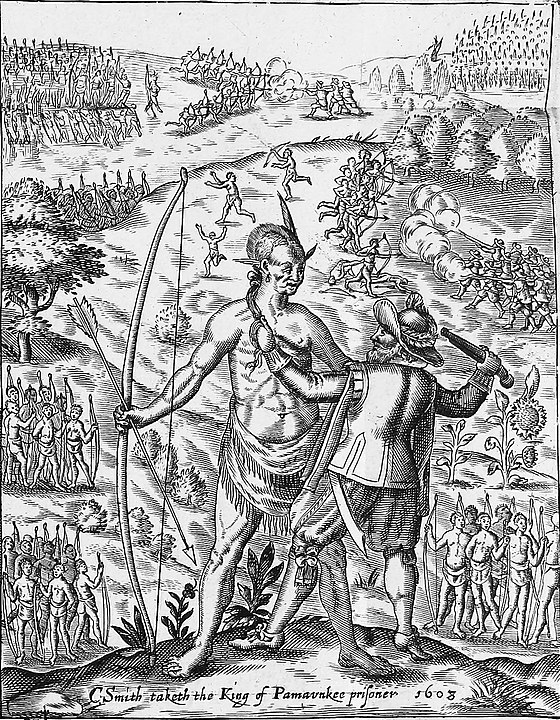

To begin with, he claimed that even before coming to the New World he had accomplished deeds of derring-do against Europe’s age-old enemies, the Turks. As a volunteer with the Austrian forces on the Hungarian and Transylvanian border, he had, he alleged, beheaded three Turks in open combat, winning the title of captain and a coat of arms for his trouble. Subsequently, he had been enslaved; befriended in Turkey by “a noble gentlewoman of some claim”; and sent around the Black Sea before returning to England. At Jamestown a few years later, he claimed, he had assumed command of the struggling colony and saved it from starvation by obtaining food from the: Indians. To crown it all there was his tale—one of the most appealing in early American history—of his last-minute rescue from death by the beautiful Indian princess Pocahontas.

But did the rescue actually take place? Did Pocahontas love Smith, and did she pine for him after his departure? Was he really the subjugator of “nine and thirty kings” in his Indian forays? Was he really Jamestown’s savior, and were later American colonies actually, in his words, “pigs of my own sow,” and, anteriorly, what about those three decapitated Turks?

A few faces about John Smith are undisputed. He was born humbly in 1580, a son of a “poore tenant” who held farmland in Lincolnshire. At fifteen the boy was apprenticed to Thomas Sendall, a wealthy merchant, he found this too dull, and, after the death of his father in 1596, went abroad as a soldier of fortune, meeting his first action in the Low Countries. In 1601 he joined the Austrians as a volunteer against the Turks. Ferocious and merciless fighters who in the sixteenth century had threatened the very gates of Vienna, the Turks were generally regarded as the chief threat to European civilization. No wonder John Smith found in them suitable enemies.

Whatever his adventures in the wars, he returned to England in 1604. He was only 26 when the Virginia Company received its patent, but he so impressed the organizers that in spite of his lack of pedigree they sent him out in 1606 as a member of the resident council appointed by the company to manage the colony. En route he was imprisoned “because his name was mentioned in the intended and confessed mutiny.” Alter his release, he explored the country and procured food for the famished colony. It was on one of these expeditions, Smith later related, that the Pocahontas incident look place.

Back at Jamestown he was again accused by his council enemies, this time on a charge based on the fact that he had lost two of his men to the Indians. He was sentenced to death, but on the eve of his execution, Captain Christopher Newport, who had been in command of the three ships that had brought the original colonists to Jamestown and who had subsequently gone back to England for supplies, returned and saved Smith’s life.

Restored to grace, Smith led exploring parties to Chesapeake Bay and the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers. During the terrible winter of 1608, he assumed dictatorial powers and again managed to obtain from the Indians enough food to keep the Englishmen alive. Whether or not he saved the settlement, he certainly alienated most of its leaders. At one point, when Newport returned a second time with seventy settlers, among them a perfumer and six tailors, Smith, never one to keep his opinions to himself, penned a Rude Reply to his London superiors:

“When you send againe I entreat you rather send but thirty carpenters, husbandmen, gardiners, blacksmiths, masons, and diggers up of trees, roots, well provided, than a thousand of such as we have. For except we be able to lodge and feed them, the most will consume with want of necessaries before they can be made good for anything.”

George Percy, youngest of the eight sons of the eighth Earl of Northumberland, thought Smith “ambityous, onworthy, and vayneglorious.” Edward Maria Wingfield, aristocratic first president of the council in Virginia, claimed Smith had “told him playnly how he lied” about his adventures with the Indians, thus starting the interminable debate over the Captain’s veracity. In the midst of all this wrangling, Smith was severely wounded by a gunpowder explosion and returned to England in October, 1609.

Surely he had been a key figure in the colony’s beginning. But savior? There the quarrel begins.

About Smith no one seems to be neutral. His “ould soldiers” considered him a fearless commander, “whose adventures were our lives and whose losse, our deaths.” Alter carefully studying Smith’s works, Edward Arber, the scholarly nineteenth-century editor of Smith’s works, stated he had “the character of a Gentleman and Officer.” In addition to many authors’ opinions, we have Smith’s own work. Though his True Relation of Occurrences and Accidents in Virginia was published in 1608 (it did not mention his rescue by Pocahontas), most of Smith’s accounts were written when his days of exploration were over. After three shorter volumes, published in 1612, 1616, and 1620, he wrote his longest and most important work, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles (1624). Here we find, for the first time, the Pocahontas story. Euphuistic and partisan, the book is nevertheless as accurate as those of most Elizabethan historians. Smith’s historical reliability was generally accepted until after his death in 1631.

For years, American writers tended to take his romantic story as true. Noah Webster included it in eighteenth-century editions of The Little Reader’s Assistant . “What a hero was Captain Smith! How many Turks and Indians did he slay!” Further proof of the national admiration for Smith came with the portrayal of Pocahontas Saving the Life of Captain John Smith above the west door of the new Capitol rotunda in Washington. When the Knickerbocker poet James Kirke Paulding traveled through Virginia in 1817, he observed: “Fortitude, valor, perseverance, industry, and little Pocahontas were their tutelary deities.” What if the editor of the North American Review , in July, 1822, made light of Smith, who “challenged a whole army in his youth, and solaced his riper years in the arms of the renowned Pocahontas”? Yankee jealousy, that was all.

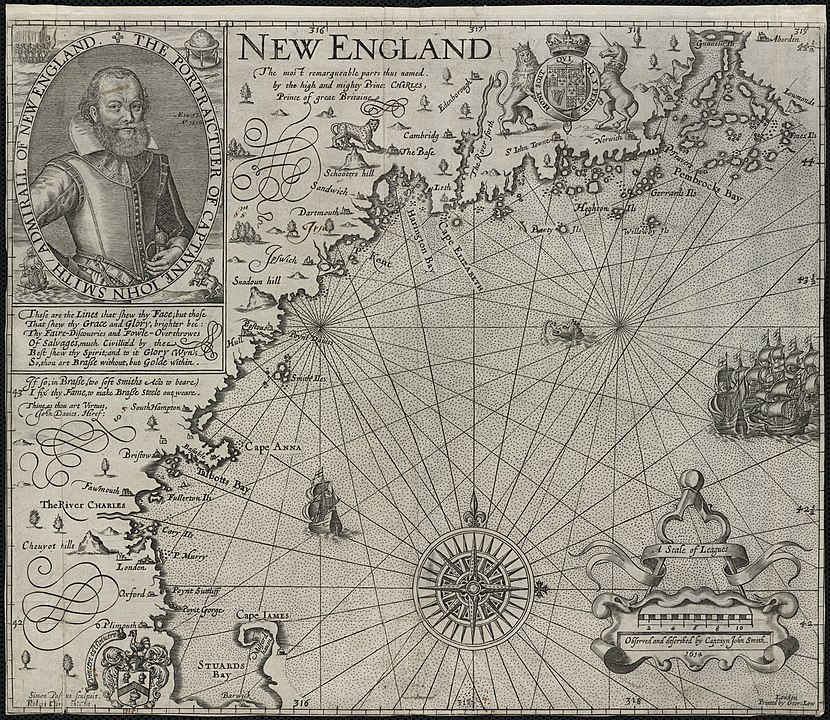

Plays like J. N. Barker’s The Indian Princess, Robert Owen’s Pocahontas, and John Brougham’s Po-ca-hon-tas or the Gentle Savage emphasized her dramatic rescue of Captain Smith. So did scores of “Indian” poems in ante-bellum journals. By 1850 the traditional picture of John Smith as savior of the Virginia colony, and of Pocahontas as his rescuer at the execution block, had not been seriously challenged. If the Captain found his chief defenders in Dixie, he at least had few detainers in the area he himself had named New England, when he explored that region several years after his Jamestown adventures.

After the mid-nineteenth century a major attack on John Smith began to shape up. In his 1858 History of New England, John Gorham Palfrey was “haunted by incredulity” concerning some of the Captain’s adventures. Charles Deane, Boston merchant and historian, looked further into the matter and decided that Smith was a notorious liar and braggart who had invented the story of his rescue by Pocahontas after the lapse of many years. None of Smith’s contemporaries knew of the episode, which Deane concluded was a fabrication.

So matters stood when the Civil War broke out. During the bitter postwar years, an abler historian than Palfrey or Deane—Henry Adams—got into the controversy. Adams had just returned from studying in Germany and was anxious to display his new methodology. In an article on John Smith in the North American Review for January, 1867, he set down for textual comparison parallel passages from Smith’s A True Relation and his Generall Historie. He found the Pocahontas rescue story spurious and labeled Smith incurably vain and incompetent. Adams thought the readiness with which Smith’s version had been received less remarkable than “the credulity which has left it unquestioned almost to the present day.” While the Nation doubted it “Mr. Adams’ arguments can be so much as shaken.” the Southern Review thought historians dealing in black insinuations were “little worthy of credit, especially when their oblique methods affect the character of a celebrated woman.” The Review struck the sectional note that would mark the Smith controversy for decades:

“If Pocahontas, alas, had only been born on the barren soil of New England, then would she have been so beautiful as she was brave. As it is, however, both her personal character and her charms are assailed by knights of the New England chivalry of the present day.”

The Yankee knights had only begun to fight. Noah Webster’s Schoolbook gave way to Peter Parley’s, which concluded from Smith’s life “that persons, at an early age, have very wicked hearts.” Moses Coit Tyler and Edward T. Channing, highly respected scholars, found more bluster than veracity in Smith. Charles Dudley Warner observed that the Captain’s memory became more vivid as he was further removed by time and space from the events he described.

Edward D. Neill went further. In Captain John Smith. Adventurer and Romancer , he pronounced Smith’s coat of arms a forgery, found the Pocahontas rescue incredible, and labeled Smith’s works “published exaggerations.” Neill’s Pocahontas and Her Companions attacked not only Pocahontas but also her husband, John Rolfe. This, Virginians thought, was a low blow; for it was Rolfe who had perfected the process of curing tobacco, which gave the colony a money crop; it was he who won the hand of the Princess, which gave Virginia peace at a time when the Indians might have driven the colonists into the sea. And what did Neill say of this wedding? He said it was a disgraceful fraud!

Virginians rallied to the defense of their hero, and leading the attack was William Wirt Henry, Patrick Henry’s grandson, a lawyer, a state legislator, and president of the American Historical Association. In 1882 he published “The Settlement of Jamestown, with Particular Reference to the Late Attack upon Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and John Rolfe.” With care and ingenuity he evolved explanations for the questionable parts of their stories.

Henry never doubted that the success of the Virginia Colony had depended on the Captain. “The departure of Smith changed the whole aspect of affairs. The Indians at once became hostile, and killed all that came in their way.” To the Indian princess Pocahontas he assigned a religions role and mission. She was, in Henry’s opinion, “a guardian angel [who] watched over and preserved the infant colony which has developed into a great people, among whom her own descendants have ever been conspicuous for true nobility.”

Equally qualified to fight for Smith was Wyndham Robertson, who was raised on a Virginia plantation and chosen to be the state’s governor. Northern attacks disturbed him so much that he prepared a detailed study of Pocahontas alias Matoaka and Her Descendants through Her Marriage with John Rolfe . Taking the marriage of Pocahontas and Rolfe in 1614 as a local event, Robertson traced the subsequent family to “its seventh season of fruitage.” Among those who turned out to be related to her were the Bollings, Branches, Lewises, Randolphs, and Pages—the very cream of Virginia. Because Pocahontas’ descendants were so notable, so was she; this simple a posteriori argument ran through the whole book.

How, asked Robertson, could anyone speak ill of the Princess when the King of England and the Bishop of London had been her devotees? Her natural charm had captivated Mother England. Leaders of society had competed for her favor. She had occupied a special seat when Ben fonson’s Twelfth Night masque was staged at Whitehall; her portrait revealed a truly aristocratic countenance. “With festival, state, and pompe” the Lord Mayor of London had feted her before death cut short her dazzling career. “History, poetry, and art,” wrote Robertson, “have vied with one another in investing her name from that day to the present with a halo of surpassing brightness.”

Then from across the seas came an unexpected and devastating blow.

It was struck by a Hungarian historian and journalist, Lewis L. Kropf. Born in Budapest and trained as an engineer, he spent most of his life working and writing in London. He combed the British Museum for hitherto unknown material on English-Hungarian relations, and between 1880 and 1913 wrote copiously for Hungarian and English journals of history. He had a predilection for setting others right and for unmasking heroes, and his reputation, as well as his list of publications, grew.

In 1890 Kropf decided to scrutinize Smith’s account of his 1601–02 adventures in southeastern Europe. His findings, published in the British Notes and Queries, were damning. Not only the places but also the people in Smith’s account were pure fictions, said Kropf. At best, his tales should be viewed as “pseudo-historical romance.” Very likely John Smith had never got to southeast Europe at all.

British and American scholars, unable to re-examine the obscure Hungarian documents Kropf cited, took him at his word. They concluded that the swashbuckling Englishman was—at least so far as his pre-Virginia story was concerned—a liar. If he was this unreliable about Hungary, how could he be trusted when he wrote of Virginia? His defenders were stunned and silent.

It was sixty years before the answer came. In the 1950’s another lady, this time a Hungarian historian, came forth to rescue John Smith, and, so far as his reputation with historians is concerned, she has done even more for him than Pocahontas.

Her name is Laura Polanyi Striker. Born in Vienna and trained at the University of Budapest, Dr. Striker was an editor and lecturer before coming to America. At the request of some of her academic colleagues she examined Smith’s Hungarian story and Kropf’s interpretation of it. Her findings, which are just being made known to the historical world, put Captain Jack back in the running as an honest man.

What were the essential features of the Hungarian story, and how much of it can be checked against the existing record?

Smith claimed that he went to Hungary in 1601, hoping to fight against the Turks. When he got to Graz, Austria, he found an English Jesuit who introduced him to “Lord Ebersbaught.” Impressed by Smith’s mastery of a pyrotechnical signal system, “Ebersbaught” introduced him to “Baron Kissell,” who in turn gave him a hearing with “Henry Volda, Earl of Meldritch.” These were the chief actors in Smith’s dramatic story.

Because he could find mention of none of these people in the archives, Kropf had called Smith a liar. But Dr. Striker, more meticulous and ingenious in her scholarship, has located them all. The English Jesuit, she discovered, was William Wright. “Ebersbaught” was Carl von Herbertsdorf. “Kissell” was Hanns Jacob Khisl, Baron of Kaltenbrunn, court war counselor of the Archduke Ferdinand. “Volda” was actually Folta—one of a number of noble families which had been given domains near the place where the battles Smith described were fought. In 1602, wrote Smith, “Volda” completed his twentieth year in military service—and Dr. Striker has found confirmation of this. Smith knew what he was talking about, even to the smallest detail. The people he names did indeed exist. The truth was that Smith, like so many Englishmen before and since, had a genius, if not a passion, for misspelling foreign names.

Smith tells how “Ebersbaught” was besieged by the Turks at “Olumpaugh” (Oberlimbach). When “Kissell” came forward to break the siege, claims Smith, he was able to use pyrotechnics and get this message across: “On Thursday night I will charge to the East. At the Alarum, salley you.” Another of Smith’s fireworks tricks made the Turks think they were being attacked on the left. When they rushed troops there, “Kissell” attacked on the right, and the Turks were overrun.

All this sounded to Kropf like pure fiction. Not so. As the re-examination of the case continued, Dr. Franz Pichler, counselor of the Styrian Archives, decided to re-enact the event on the terrain, and with pyrotechnics, such as Smith might have used. So far as he could determine, it would have been quite possible for Smith to have done just what he claimed.

Later on, when he went with “Volda” into Transylvania, Smith says he reported not to the Austrian but to the Transylvanian commander, Sigismund. Why the “unexplainable” switch in loyalty? Dr. Striker has explained it. “Volda’s” estates were in Protestant Transylvania. The Austrians were fanatically pro-Catholic, and Protestants were not allowed to fight in the Imperial Army. It seems not at all unreasonable that “Volda” might have had a grudge against the Austrians, thrown in his lot with Sigismund, and taken his new friend, Smith, with him.

Next comes the most puzzling detail of all. Smith says that under Sigismund he and “Volda” fought “some Turks, some Tartars, but most Bandittoes, Rennegadoes, and such like.” How could this be, when the enemies of Sigismund’s Transylvanians were not the Turks, but the Austrians?

Again Dr. Striker has been able to disentangle the confusing skein of Hungarian history. Sigismund had made a special agreement with the Austrian General Basta to drive out of the country an army of Hajdus, a people of Turkish-Hungarian stock whose polyglot mercenary troops were plaguing the region. Unable to control them himself, Basta promised Sigismund a truce if he would do the job. Kropf failed to find proof that this agreement existed, and concluded that Smith was a liar. Actually, Smith knew enough to place these Hajdus in exactly the right spot and at the right time, as the documents proved.

Unable to dislodge the Hajdus from their fortress, Sigismund’s troops camped outside the walls, from which their enemies taunted them. Finally, a Hajdu fighter sent a challenge for a trial at arms. Smith met the warrior, defeated him, and cut off his head. He did the same to two others. When the heads were presented to the General, Smith was rewarded with a “faire horse richly furnished, a Semitere, and belt worth three hundred ducats.” He even got a coat of arms for his valor.

Highly improbable, Smith’s enemies have always declared. Ridiculous, said Kropf. Yet a seventeenth-century chronicler named Szamoskoezy (just think what Smith might have done with a name like that!) wrote a description, hidden for centuries in manuscript form, which jibes exactly with Smith’s description of the duels!

Having overcome the Hajdus, Sigismund attempted to get control of Transylvania. He was unable to do so, and most of his troops were slaughtered. John Smith related that he himself was left for dead on the field, restored to strength because he looked worth ransoming, and sold as a slave into Turkey. From there, his account continues, he was taken to the Crimea, and eventually escaped and got back to England. After a short rest he was ready to stretch his incredible luck by setting out for the New World.

“He could not possibly have written as he did about Hungary without having lived through the events he described,” Dr. Striker has concluded. “It is time we gave him full credit for being not only a valiant fighter, but an acute historian and chronicler as well.”

No one can claim that clearing Smith’s name in southeastern Europe necessarily validates all he wrote about Virginia. But at least the reverse logic used so frequently by his detractors—If he lied so outlandishly about Hungary, how could he be trusted elsewhere?—applies. If he was so accurate and trustworthy in Hungary, isn’t there reason to trust him in Virginia?

Quick to anger but quicker to forgive, bushy-bearded Captain Jack must be accepted for what he was—the last of the knights errant. Possessing no crafty, subtle mind, he acted first and pondered afterwards. If he had any philosophy, it was to meet problems as they came and make the most of every opportunity. This stepchild of Ulysses was never plagued with indecision or soul-searching. He never doubted, up to his dying day, that he could accomplish the impossible- perhaps because, on some occasions, he did. His pageantry and pretense were so incongruous in the vast wilderness that there is a Don Quixote-like pathos about his story. If he had been fighting windmills and not Indians, we might find the whole thing quite amusing. John Gould Fletcher writes:

“He had displayed brilliant courage, but not deep wisdom; grappled for power, but not for the power that comes through a deep understanding of human limitations; seen strange seas, talked with strange people, and lived through an epic.”

Americans who know nothing else about early American history can recount the dramatic tale of Smith’s rescue on the block by the beautiful Indian princess Pocahontas. Whether or not Pocahontas really saved the gallant Captain at the execution block, and whether or not they were strongly attracted to each other, Pocahontas frequently visited Jamestown while Smith was there and stopped these visits after he had departed. We will never know just what the Captain meant when he called her the “nonpareil of Virginia.” If he did not owe his life to her on that day in the forest, he did—in a historical sense—once he wrote about her years later.