Seventy-five years ago, Allied soldiers made a daring amphibious landing behind German lines and were soon surrounded in what would become one of the toughest battles of World War II.

-

Winter 2019

Volume64Issue1

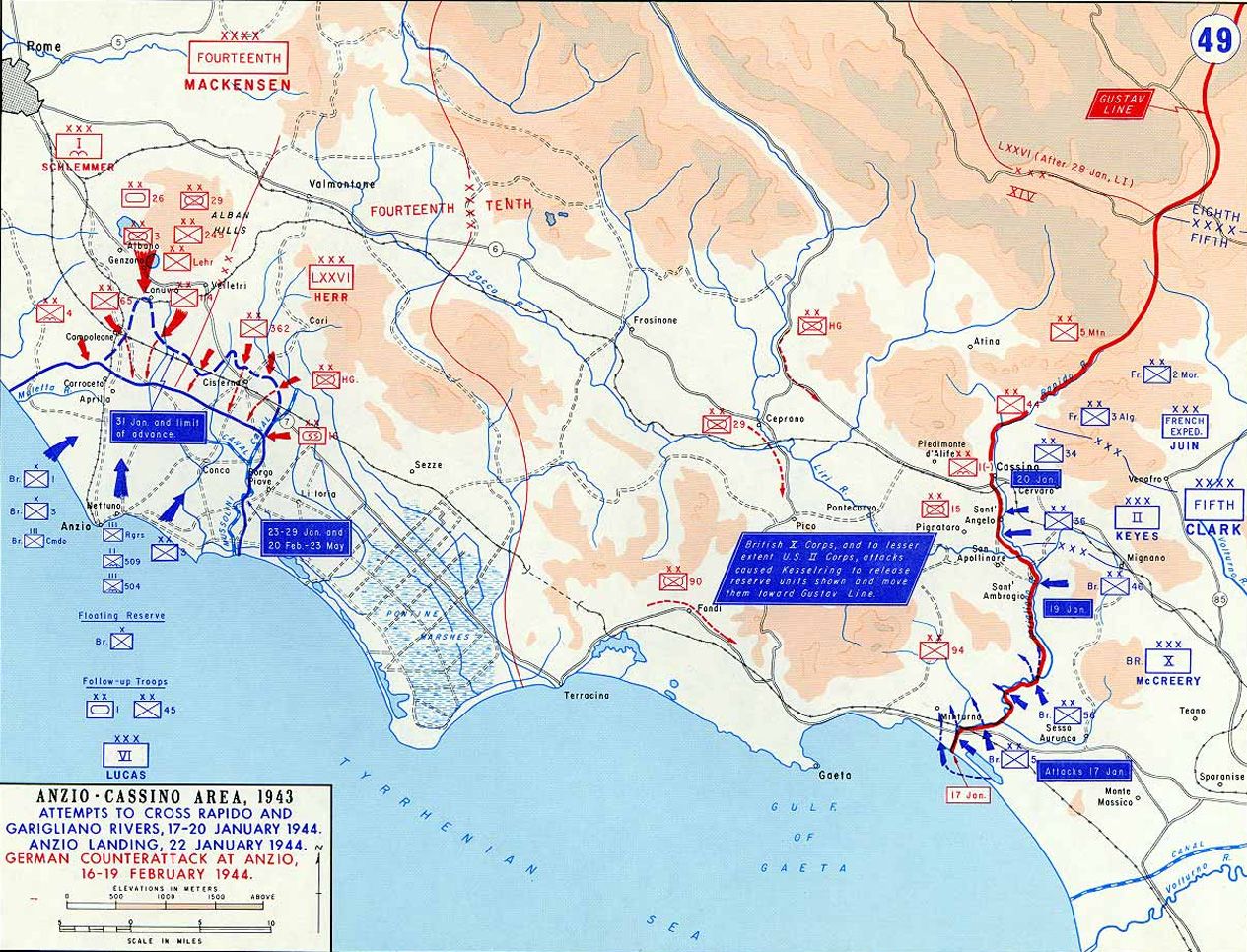

In the predawn darkness of January 22, 1944, an amphibious force of 36,000 members of VI Corps, a joint U.S.-British command, and a part of Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s combined U.S.-British Fifth army, was heading toward the German-held beach towns of Anzio and Nettuno, on the eastern coast of Italy, just 40 miles south of Rome.

The Germans weren’t expecting such an audacious operation. Since the previous October, German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring’s Army Group C had kept the Allies from advancing up the Italian peninsula by bottling up both Clark’s Fifth and Lt. Gen. Oliver Leese’s British Eighth Army below the Gustav Line, a formidable defensive line that ran the width of Italy and was anchored at Monte Cassino, 100 miles from Rome.

The Anzio-Nettuno invasion, known as Operation Shingle, was designed as an “end run” around the western flank of the Gustav Line. While the idea for Shingle had been Clark’s brainchild, it was nearly stillborn because so many American and British assets—men, materials, and shipping—were in the process of being diverted from the Mediterranean Theater to the United Kingdom in order to prepare for the upcoming Operation Overlord, the invasion of northern France.

But British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who had fought long and hard to maintain a strong Allied presence in the Mediterranean (believing that it represented the “soft underbelly” of Hitler’s Europe), was an early and enthusiastic supporter of Shingle, and he pushed it forward even when others argued against it.

Churchill felt strongly that Kesselring would be so unnerved by an Allied landing behind the Gustav Line that he would panic and order the German Tenth Army to abandon its positions and high-tail it northward, leave Rome undefended, and perhaps even head all the way to the Alps.

Shelved and then reincarnated on a couple of occasions, Shingle was finally given a last-minute reprieve and put into action.

And so, hundreds of ships filled with men, tanks, and artillery pieces slipped out of Naples harbor after dark on January 21, sailed north, and began discharging men and their equipment onto the silent sands both north and south of Anzio-Nettuno the next morning.

Leading the operation was Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, whose VI Corps had barely managed to hold the Salerno beachhead the previous September. For the next three months, VI Corps, along with Clark’s Fifth Army and the British Eighth Army on the Adriatic side of Italy, crawled their way north, battling both the rugged Apennine Mountains, the increasingly foul autumn weather, and the Germans’ tenacious defense.

Lucas, age fifty-six, was a solid, if uninspiring, leader not given to reckless, aggressive charges towards the enemy. And Clark, his superior, had not exactly demanded a hell-bent-for-leather charge from Lucas. “Don’t stick your neck out as I did at Salerno, Johnny, or do anything foolish,” he counseled his subordinate shortly before the operation began, adding, “You can forget this goddam Rome business.”

Lucas took his vague orders to mean that he was not expected to make a mad dash for Rome but, rather, make a landing, consolidate his beachhead, and wait for more troops and supplies to arrive before venturing very far inland. No one knew what the enemy’s reaction would be, but it was expected to be violent and powerful.

Splashing ashore in the dark, the British 1st Division and U.S. Third Infantry Division swiftly overcame what little opposition was thrown at them, marched a few miles inland, and then dug in to await further orders. The terrain around Anzio and Nettuno was virtually devoid of German troops.

The initial phase went as well as the planners of Operation Shingle could have hoped for; Lucas certainly thought so. He wrote in his diary with pride, “We achieved what is certainly one of the most complete surprises in history.”

This positive thought was confirmed when Clark and Field Marshal Harold Alexander, head of 15th Army Group and Clark’s immediate superior, visited the beachhead area later on D-Day to assess the situation and confer with Lucas; the two seemed pleased with the landings and the progress thus far. Alexander was especially happy that things had gone so well. Buoyantly, he told Lucas, “You have certainly given the folks at home something to talk about.”

As D-day wore on, and there seemed to be no enemy attempts to counterattack them, the men on the beachhead grew confused. One of the British soldiers grumbled, “What were we messing about at? Rome was only thirty miles up the road; we could have been drinking vino with the Pope by now.” It was a grumble shared by 36,000 others

With the lone paved Anzio-Rome highway wide open, getting to the capital city quickly would have been relatively easy, but the salient created by such a thrust up the highway worried Lucas. According to one 3rd Infantry Division officer, the slim column would have been mercilessly attacked and destroyed. “I don’t know why people don’t understand that,” he lamented.

Although caught by surprise but not without expectation, Kesselring reacted swiftly to implement contingency plans; he told 10th Army commander Heinrich von Vietinghoff to pull some of his divisions out of the Gustav Line and send them to Anzio to seal off the beachhead. He also ordered Eberhard von Mackensen to assemble as many units throughout Italy and surrounding countries and activate them as the Fourteenth Army, and also get them on the roads to Anzio.

Shingle quickly turned from brilliant invasion to bloody stalemate, as the Germans brought in thousands of infantrymen and hundreds of panzer tanks and artillery pieces (not to mention aircraft and U-boats) to pound the invaders.

Some of the toughest fighting of the war in Europe would ensue over the coming months. Much of the fighting swirled around the small, strategically important village of Aprilia (sometimes called “the Factory” by the troops), located about 10 miles north of Anzio on the Anzio-Rome highway; the settlement exchanged hands several times during the course of the battle.

Early on, elements of Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott’s 3rd U.S. Infantry Division, along with the U.S. 6615th Ranger Force, under the its founder, Col. William O. Darby, were sent to evict the enemy from the city of Cisterna, on the right flank of the beachhead. But the 3rd Division was stopped cold and Darby’s Rangers were ambushed and obliterated trying to reach the objective; despite several American attempts, Cisterna would remain in German hands until the end of May 1944.

Rarely were any “fresh” troops brought in to reinforce the beachhead and gain the upper hand. The several other divisions—both British and American—that did arrive at Anzio over the next few months had already exhausted themselves at Monte Cassino, the Rapido River, and at other points along the Gustav Line. Yet, they were all that Clark had available to him.

The middle of February saw the Germans make their strongest push yet to obey Hitler’s dictum to Kesselring: “Lance the abscess south of Rome.” Massive, unrelenting human-wave attacks, reminiscent of the First World War, coursed across the shell-cratered no-man’s land between the two sides, and both sides unleashed stupendous cascades of artillery.

Beachfront hospitals, too, were the subject of German shelling, both accidental and deliberate, and the steadfastness of the doctors and nurses was no less heroic than that of the combat soldiers. At the height of the German onslaught, a plan was made to evacuate the nurses, but they would have none of it; they vowed to stay as long as there were wounded soldiers to care for.

At last, when the titanic struggle took a short breather following the February 16-19 assaults, General Lucas, who had earned the ire of Churchill, Alexander, and Clark for not being more aggressive, was relieved of command of VI Corps. On February 23, Lucian Truscott was moved from commanding the 3rd Division to become head of VI Corps. But there was still much fighting ahead.

Acts of heroism were too numerous to chronicle. But so difficult was the fighting that 26 Americans were awarded the Medal of Honor—half of them posthumous—during the course of the four-month-long battle. Two Brits received their nation’s highest honor: the Victoria

Cross, although, to be honest, medals for heroism could have been dispensed by the bushel full.

Much of fighting took place in total darkness. While on a night patrol near Cisterna, Private James Aurness, 3rd Infantry Division, was point man for his platoon. Moving as stealthily as possible through a small vineyard, Aurness froze as he heard voices up ahead of him.

A guttural voice yelled and enemy fire burst out ahead of him. He said, “I’d walked right into a German machine-gun nest. I was hit in the right leg but was able to leap over a row of vines anyway, out of the line of fire. Then I fell to the ground in excruciating pain. It felt like the bones in my lower right leg had been all shot to hell. Intense fire started coming at me from both sides.

“I was almost killed when a ‘potato masher,’ a German concussion grenade, went off near me. The explosion literally lifted me off the ground. The Germans had two machine-gun nests, with infantrymen spread out on either side. The firing was low, about eighteen inches off the ground, so I had to practically hug the earth not to get hit.

“There were about fifteen Germans; we had forty riflemen firing and throwing grenades, backed up by a light machine gun. The shooting was intense, but eventually our guys overran them and took them out.” Aurness lay bleeding and in pain in the vineyard for quite some time, struggling to maintain consciousness, until a medic found him and began applying first aid; Aurness realized his leg bones were severely splintered.

“Penicillin wasn’t used at this point, but sulfa powder did an adequate job of sterilizing the wounds,” Aurness later recalled, “He poured some on and gave me a shot of morphine in the stomach…. Many of the others who got hit were in terrible condition, so I was lucky…my wound was not life-threatening.” (After the war, Aurness gravitated to Hollywood, changed the spelling of his name, and enjoyed success as Marshall Matt Dillon in the TV series, Gunsmoke.)

Another 3rd Division soldier who would later gain fame was a baby-faced sergeant from Texas named Audie Leon Murphy He had a chilling experience when he arrived at Anzio as a replacement, his normally 200-man company reduced to thirty-four. He wrote, “As we hike inland, jeeps drawing trailerloads of corpses pass us. The bodies, stacked like wood, are covered with shelter-halves, but arms and legs bobble grotesquely over the sides of the vehicles. Evidently Graves Registration lacks either time or mattress covers in which to sack the bodies.”

Murphy later became the most-decorated American soldier of WWII when at age 19 he single-handedly held off an entire company of German soldiers for an hour at the Colmar Pocket in Alsace-Lorraine in January 1945, then led a successful counterattack while wounded and out of ammunition. He received the Medal of Honor and every military combat award for valor available from the U.S. Army, as well as French and Belgian awards for heroism.

James Safrit of the 45th Division recalled that, “When darkness came, we posted guards. One man slept, or tried to, while his buddy pulled guard duty — two hours on and two hours off. I had drifted off to sleep when Burns shook me and whispered, ‘Wake up! Krauts!’ All he had to say was ‘Krauts’ and I was wide awake. We sat in our hole trying to see in the pitch-dark night.”

Safrit noted that he and his buddies soon surmised that the enemy had fortified themselves with booze and he could hear “German voices singing at the tops of their lungs. As they came closer, we could tell they were as drunk as skunks. By this time, the whole platoon was listening and waiting. Those crazy bastards were really living it up. We were almost ashamed to do what we did when they came in front of our holes. We opened fire and the singing became a rattle. Then everything was quiet. Eventually, after we were sure there were no more coming, the medics came up and carried them off to Graves Registration.”

Much of the heaviest fighting swirled around a feature called the Overpass by the Americans and the Flyover by the British. It was an unfinished railroad line that rose above the main highway between Aprilia and Anzio; its narrow opening was the only place where the Germans stood any chance of splitting the Allies’ defensive line and was thus heavily defended.

Whether hopped up on alcohol or amphetamines, the Germans continued to throw themselves into their suicidal charges against the Allied lines. Hans Schuhle, a member of the German 7th Company, Infantry Lehr, somehow survived to write of his experiences. He remembered that his regiment was supposed to lead the charge from Aprilia down toward the Overpass — a distance of two or three miles — but their late start was immediately met by the seemingly endless barrage of Allied shells — including those of the Navy and bombs dropped by the Twelfth U.S. Air Force.

“The terrible fire had already completely demolished us before the attack,” Schuhle said, “and our morale was destroyed. With guns we were threatened by our officers and non-commissioned officers and forced to leave our shelters and go into the attack. It was already 9:00 AM when we began with this attack. Through deep swamps, always looking for a new shelter, we hardly reached the escarpment of the railroad. At that time the enemy artillery became even stronger and we could find shelter only in the shellholes.

“It was then that I found myself with an American in the same hole. We looked at each other…. We stared into each other’s eyes, neither of us reacting. I then understood that the American infantry were under the fire of their own artillery.” Schule had the presence of mind to take the American prisoner and took him back to his own lines, refusing an order by an officer to kill the Yank.

Letters found on the bodies of the enemy dead often gave Allied intelligence a picture of German morale. A G-2 officer from the 45th Infantry Division found a poignant, unfinished letter in the pocket of a German tunic: “Shortly after you get this,” the soldier had written to his mother, “I will be dead. Our officers have lied to us. We are low on ammunition and low on food. The war is lost. Germany is lost.”

Somehow, though, the Germans managed to continue their attacks, preferring to die as heroes than as cowards. After fighting off one particularly difficult German assault that left only a handful of British soldiers defending a key feature, a group of American tankers reached the embattled group.

Leading the tank column, Maj. Gen. Ernie Harmon, commanding the 1st U.S. Armored Division, said, “It was on the day of my armor’s farthest advance that I had the privilege of relieving a group of British soldiers who had held a position under the most punishing circumstances. They belonged to the Sherwood Foresters. My tank climbed the hill and then I called a halt and got out to walk. There were dead bodies everywhere. I had never seen so many dead men in one place. They lay so close together that I had to step with care.

“I shouted for the commanding officer. From a foxhole there arose a mud-covered corporal with a handlebar moustache. He was the highest-ranking officer still alive. He stood stiffly at attention.d

“How is it going?” I asked. The answer was all around us.

“Well, sir,” the corporal said, “there were 116 of us when we first came up and there are now sixteen of us left. We’re ordered to hold out until sundown, and I think, with a little good fortune, we can manage to do so.”

Looking at the handful of mud-and-blood-caked Tommies smiling at him, Harmon noted, “I think my great respect for the stubbornness and fighting ability of the British enlisted man was born that afternoon.”

Of course, after weeks of all-out battle, the Germans no longer had the strength to crack the Allied line, but the British and Americans still did not have the numerical superiority to break out of their beachhead, which propagandist Axis Sally proclaimed to be the “world’s largest self-sustaining prisoner-of-war camp.”

It was not until May 1944, with Clark and Alexander knowing that the long-awaited cross-Channel invasion was nigh, that the final effort was made to smash through the Gustav Line, followed by the breakout from Anzio. With Allied forces at last pushing the Germans from their Gustav Line positions and back toward Rome, Truscott’s VI Corps began its breakout.

The first few days were some of the bloodiest of the entire campaign. The Allies would sustain 43,000 casualties including 7,000 killed, while the Germans and Italians suffered a similar number of killed, wounded or missing. But eventually the Americans and Brits overwhelmed the defenders and began the dash to Rome.

Huge, flower-throwing throngs turned out to welcome the Yanks as they paraded through the ancient streets on June 4. Although one of the three major Axis capitals had finally fallen, the joy and attention was short lived; two days later, Allied armies hit the beaches of northern France and the war in Italy ceased being news.

Operation Shingle has been characterized by historians as a “dismal failure,” “a squandered opportunity,” and “an offensive blunder.” But, given the vague orders, the small invasion force, and the unreasonable, over-optimistic expectations (such as thinking that Kesselring had no additional reserves and would be panicked into abandoning the Gustav Line) perhaps a quick, stunning victory was never in the cards.

The real story of Anzio is not in its offensive failure but rather the overlooked, extraordinary courage with which the common British and American soldiers—often fighting side by side—called upon to beat back every attempt by the Germans to crack their line and push them back into the sea.

The British and American soldiers stuck at Anzio in their muddy foxholes probably did not yet realize it, but they had pulled off a remarkable feat. Those who were still alive had fought off some of the most severe attacks in recorded history. They had persevered against horrendous artillery barrages and aerial assaults. They had held fast against waves of infantry and panzers. They had seen their buddies killed next to them and die in horrible ways. They had suffered grievous wounds yet returned to their duty stations. They had lived in mud and squalor, surrounded by foul smells and even worse sights, with absolutely no guarantee that they would prevail in the end. They, as a group, had taken every punch the Germans could land and were still standing—bloody but unbowed. They had, in short, accomplished the impossible.

And, in larger sense, the tenacious Yanks and Tommies prevented the Germans from pulling troops out of Italy to reinforce their beleaguered Eastern Front or to substantially strengthen their positions along the so-called Atlantic Wall in order to prepare for the Allies anticipated cross-Channel invasion.

There truly was a triumph at Anzio.