The first significant Union victory in the Civil War is now honored at one of the newest National Monuments. It was a battle too often ignored by historians and the public.

-

Winter 2019

Volume64Issue1

On February 12, 2019, the U.S. Senate passed conservation legislation that if signed by the president will protect millions of acres of land and establish four new National Parks. Among them is the new Mill Springs National Monument, site of the first Union victory in the Civil War. We asked historian Jack Hurst, author of a respected trilogy of books on the Western theater of the Civil War, to tell us why this forgotten battle deserves more attention. Portions of this essay were excerpted from one book in his series, Men of Fire: Grant, Forrest, and the Campaign that Decided the Civil War (Basic Books). –The Editors

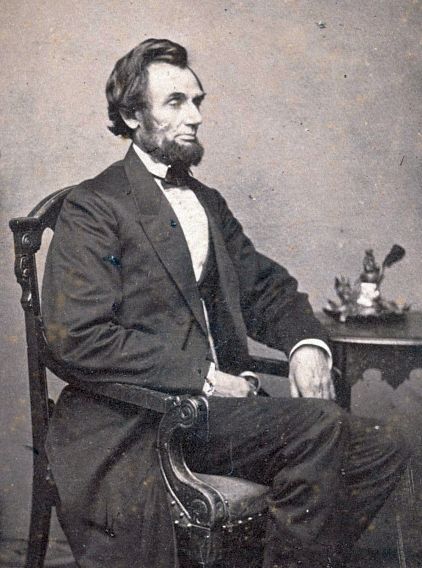

Since the start of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln had been obsessed with eastern Tennessee and Kentucky. He was familiar with the area, having been born in a one-room log cabin near Hodgenville, Kentucky, in 1809. Both his parents, and later his step-mother, were from the state.

Lincoln knew that the foothills of the western Appalachians were like a long knife of Union-loving territory lodged in the Confederacy’s vitals all the way down to north Georgia.

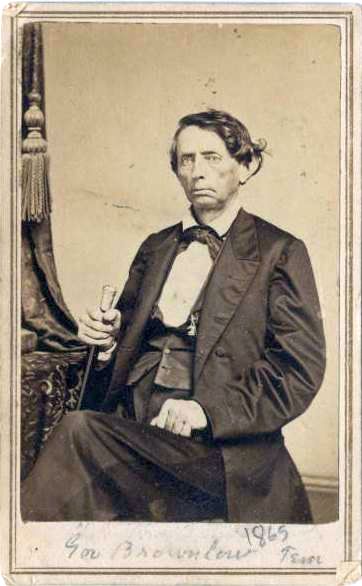

While the central and western divisions of Tennessee had voted overwhelmingly to leave the Union in June 1861, residents of the state’s eastern third elected to stay in by a margin of 32,923 to 14,780. The section’s most popular newspaper, until its suppression by the Confederates in October, was the Knoxville Whig of publisher-editor William G. “Parson” Brownlow, a poison-penned Methodist minister whose favorite printed description of the Confederacy was that it was “hell-born and hell-bound.” The Whig was a daily Bible for hardy, insular mountaineers, whose hilly farmsteads could neither support nor afford slave labor.

These tenacious people hated slavery — less from sympathy for the slaves than from deep resentment of the political dominance of Tennessee politics by their aristocratic owners. At the start of the conflict, two thousand hill men who had hardly ever left their counties before defied the new Confederacy and hired guides to lead them on foot trails through mountain passes into Kentucky to enlist in the Federal army.

Lincoln wanted to give this knife in the Confederate stomach a twist. He believed that if the area’s loyalist flame were ignited by the arrival of Federal troops, the result could cripple Confederate forces back East in front of Washington by severing Richmond’s rail lifeline to the Deep South. He also hoped capturing East Tennessee would make the region a cancer in the middle of Dixie and foster uprisings of Union-loyal elements all across the South. That early strategy of Lincoln’s would lead to the fight at Mill Springs.

Union leaders in the area and in Washington first plotted disruptions. A Rev. William B. Carter snuck out of the region in late September with a scheme to torch the railroad bridges in coordination with an army advance into East Tennessee. Carter first approached Federal officers in Kentucky and the expatriate Andrew Johnson, the eloquent East Tennessean who had derided secession and continued to serve in the U.S. Senate as the lone Southerner. Carter was sent to the top of the chain of command to confer with Lincoln and Army of the Potomac commander McClellan at the White House. They gave him a secret payment of at least twenty-five hundred dollars to bring his plan to fruition, and Lincoln issued orders for the army in Kentucky to move south and invade East Tennessee.

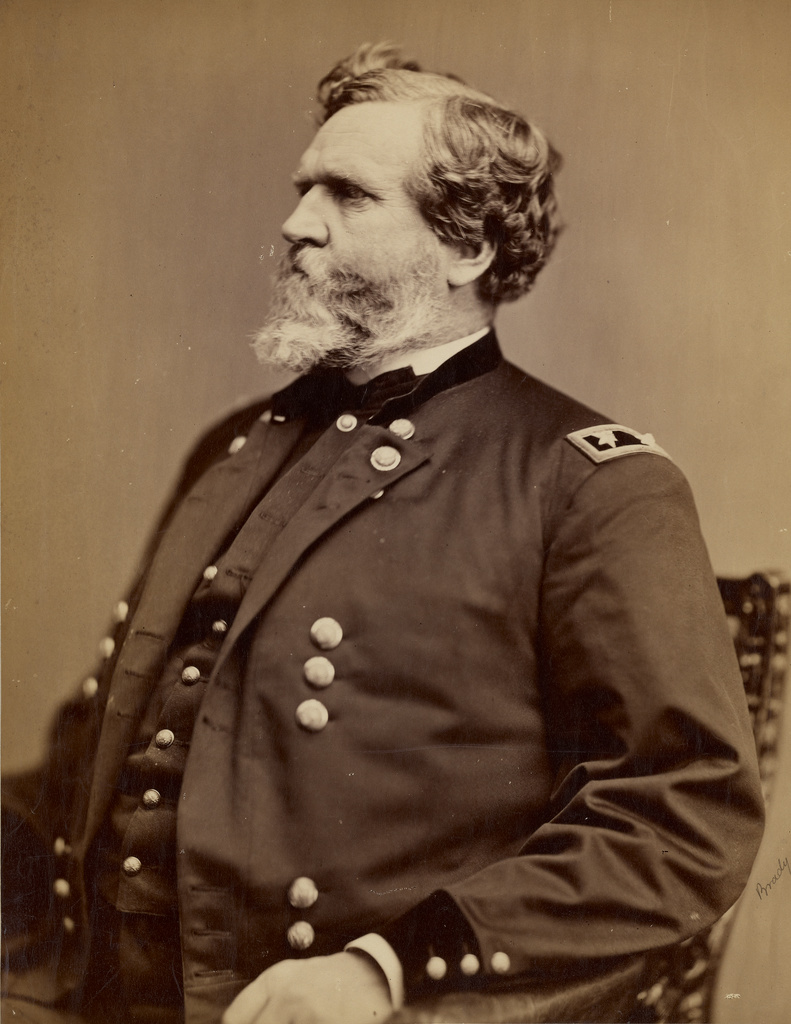

On November 8, the bridge arsonists kept their end of the bargain, even cutting telegraph wires across the region, but the army failed to invade. The Federal commander in Kentucky at the time, Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman, underwent a crisis of confidence in the face of Confederate Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston’s phony bellicosity and halted an early November move toward Cumberland Gap by Gen. George Thomas (who later earned the famous nickname, “Rock of Chickamauga” in 1863.)

The resulting harsh Confederate crackdown on East Tennessee’s loyalists with hangings and imprisonments, including the venerable “Parson” Brownlow himself, added a pall of guilt to Lincoln’s East Tennessee anxiety. Sherman, shattered, asked to be replaced and quickly was, with the highly regarded but balky career officer Gen. Don Carlos Buell.

Lincoln pushed more desperately for a drive on Knoxville, and finally, after protesting repeatedly and with reason about the miserable mountain roads and extreme supply difficulties, Buell, on December 29, gave Gen. George Thomas the go-ahead.

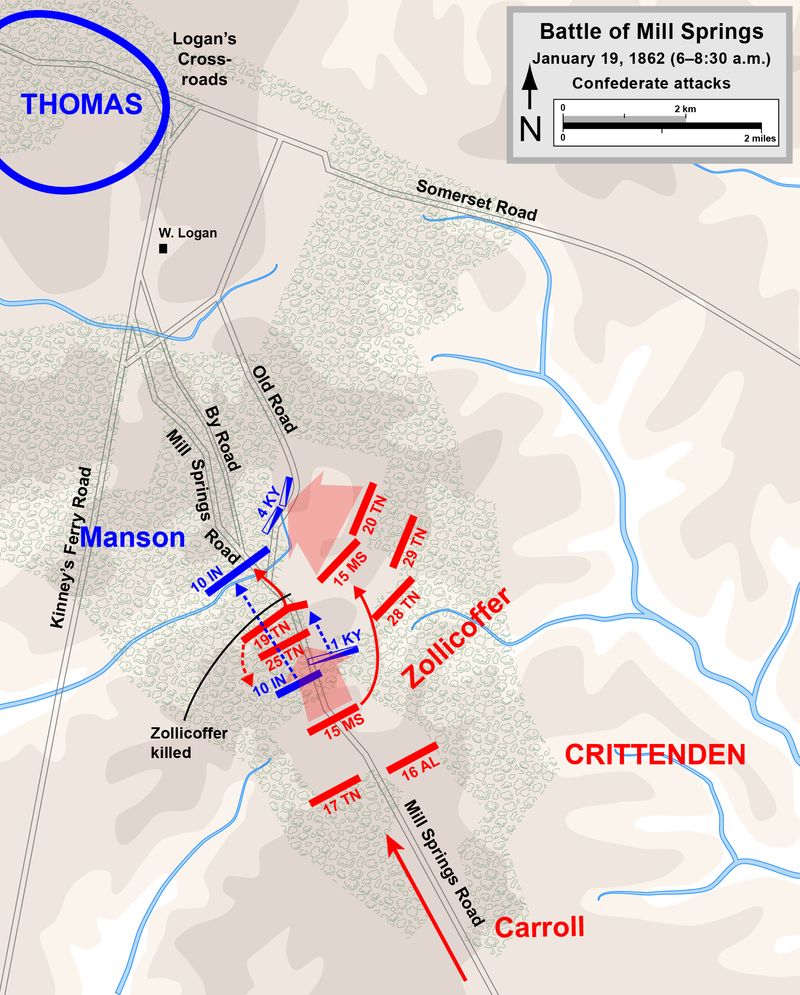

But Buell had held Thomas back so long that his deep reservations about the roads were more than justified. Such thoroughfares as existed through the mountains at all were only marginally usable in good weather, and in mid-winter they were creeks of clay. It took Thomas’s column seventeen days to travel the sixty-five miles to little Logan’s Crossroads, the junction with the road leading eleven miles south to Gen. Felix Zollicoffer’s Confederate base at Mill Springs.

See also “Grant Splits Dixie,” by Jack Hurst

This was the farthest south a Federal force had been allowed to go since the start of the war, though, and Thomas was due some credit for the achievement.

For two months, Gen. Thomas had been the man in the middle, a position he was familiar with from the war’s outset. A West Point-trained career officer and native Virginian in the antebellum army who served under Robert E. Lee, he suffered the rage of his sisters after deciding to stay with the Union. They turned his picture against the wall, destroyed his letters, and never spoke to him again.

Now Thomas was torn between the exasperation of Lincoln, McClellan, Andrew Johnson, and the many others pleading the desperate cause of the eastern Tennessee unionists and, on the other side, the mulish and aloof Buell, rival of new Missouri/Western Kentucky commander Henry Halleck for the dubious title of “McClellan of the West.”

Buell, arrogantly insecure and focused on preparing to fight rather than actually fighting, was no more disposed to offer battle than his eastern commander and even more impervious to the political necessity, at this point, of doing it. He had left Washington for his new assignment two months earlier espousing the Lincoln-McClellan idea that the East Tennesseans had to be rescued quickly, but he became quietly insubordinate on reaching Kentucky. Five days after Thomas moved out of Lebanon toward Mill Springs, Buell conveyed to Lincoln his conviction that the railroad stretching south from Louisville to Nashville, although less direct, offered the easiest route to freeing the East Tennesseans.

“I have no fear of their being crushed,” he blithely wrote McClellan.

The president, professing distress and disappointment at Buell’s revelation, quickly replied with intelligence and compassion:

“I would rather have a point on the railroad south of Cumberland Gap than Nashville—first, because it cuts a great artery of the enemy’s communication, which Nashville does not; and, secondly, because it is in the midst of loyal people, which Nashville is not . . . [M]y distress is that our friends in East Tennessee are being hanged and driven to despoil; and even now I fear are thinking of taking rebel arms for the sake of personal protection. In this we lose the most valuable stake we have in the South.”

Thomas had been volunteering for months to try to take the more direct route, through the gaps and passes along the Eastern Kentucky-East Tennessee border. Even now, it seemed a chance worth taking. As Lincoln had noted, this march would be unlike Federal operations in many other parts of the South because it would be made through remote non-slaveholding, hill-country counties where the majority of local sentiment was rabidly Unionist. And, if successful, it would cut that vital stretch of Confederate railway between Dixie’s supply-laden interior and the northern Virginia theatre on which most of Washington was fixated.

By mid-January, however, the weather had deteriorated to the point that Thomas himself questioned the wisdom of the march. He remained resolved, though, to do what he had come to do: destroy, capture, or at least chase out of eastern Kentucky the few thousand Confederates under Gen. Felix Zollicoffer who comprised the right wing of Gen. Johnston’s long, tenuous defense line. That brought Thomas, on January 17, 1862, to this road junction at the farm of a family named Logan, where he had to await four of his eight-and-a-half regiments that had fallen behind on roads plowed into frigid swamps by passage of his lead units.

With Thomas at Logan’s were infantry regiments from Indiana, Ohio, and Minnesota, the First Kentucky Cavalry, and a battery of Ohio Light Artillery. Just eight miles down the road at Somerset, there were two more brigades of Union troops under Gen. Albin Schoepf. But as the rain continued and rivers rose, Thomas feared isolation, and he ordered Schoepf to hurry out a brigade of temporary reinforcements until his straggling units could catch up. Schoepf sent the so-called Tennessee Brigade, comprised predominantly of the escaped East Tennesseans who were eager to march homeward. Their commander was Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Carter, brother of the Rev. William B. Carter who was a principal author of the bridge-burning plot.

When the Tennessee and Kentucky brigades arrived at Logan’s that evening, their soldiers had to bivouac hungry and at the mercy of the elements, their tents and rations having been left behind in wagons halted by the rising waters of Fishing Creek. The men had been forced to cross the flooding stream on foot just to get to Logan’s at all.

“Here we remained through the day and night of the 18th, exposed to the excessive rains without shelter,” reported the Twelfth Kentucky’s Col. William Hoskins.

Earlier that day, Thomas had sent two of his lagging units off with a wagon train and a day’s rations to capture a large Confederate forage party reported to be camped six miles from Logan’s. Normally prudent, Thomas had let himself get separated from his four lagging regiments near a significant force of the enemy and then had neglected to command his men to entrench. But he may have committed some of these seeming errors intentionally.

Thomas originally planned to attack the Confederates’ left flank at Beech Grove, across the flooded Cumberland from Mill Springs, so as to separate them from the best places to re-cross the river while Schoepf assaulted them frontally. But Schoepf, a half-Polish Austrian who had fought in Europe, dissented and proposed an alternative scheme to draw the Confederates into the open. Thomas, who had battled Seminoles in Florida and Comanches in Texas, liked the trickery idea enough to forward it to Buell. Although he never said so in a subsequent report, Thomas apparently hoped to provide a target inviting enough to lure the Confederates out of the Beech Grove trenches. Entrenching his own men would hardly have done the trick.

To insure that his encampment would have adequate warning of an attack, though, Thomas did order the positioning of three successive picket lines.

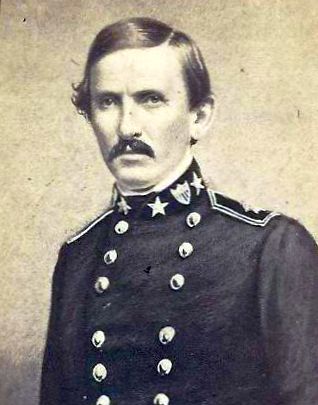

At Beech Grove, new Confederate wing commander George B. Crittenden — youngest son of Union loyalist Sen. John J. Crittenden of Kentucky and brother of Federal Brig. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden — knew he was in precarious straits. A few weeks earlier, in early December, Zollicoffer had crossed most of his men over the Cumberland River to Beech Grove from Mill Springs — one day before receiving a letter from Johnston ordering him not to do so. Here, the river made a horseshoe bend to the south, and Zollicoffer thought his force needed to be inside the horseshoe.

“The river protects our rear and flanks,” he wrote Johnston on December 10. He did not see that, as Johnston soon emphasized to Crittenden in Knoxville, he had “the enemy in front and the river behind.” That, of course, risked doom. The rains having made the river unfordable, Zollicoffer had become trapped.

On December 13, just four days after Zollicoffer’s errant crossing of the river, Crittenden was assigned command over eastern Kentucky — and over the hapless Zollicoffer. Crittenden quickly ordered Zollicoffer to re-cross to Mill Springs, but, on arriving there to take command himself, Crittenden found Zollicoffer still at Beech Grove with only two flatboats and a “small stern-wheel steamboat,” the Noble Ellis, “unsuited for the transportation of horses” or artillery.

Crittenden ordered the building of larger craft, but he had hardly given the command when, on January 17, cavalry scouts reported Thomas “moving across my front on the road . . . towards Somerset, with the mention of uniting with the Somerset force and attacking Beech Grove.”

The next day, as Thomas perhaps intended when he sent two of his lagging regiments in pursuit of the Confederate forage party, Crittenden’s informants discovered not only that Thomas was camping at Logan’s but also that he was awaiting the arrival of “re-enforcement” by troops from his rear as well as others from Somerset. “Crittenden was also informed by cavalry scouts that Fishing Creek between Somerset and Logan’s was flooding “and would prevent . . passage by any infantry force.”

Knowing he had to act fast, Crittenden reacted with boldness, or maybe panic. Contrary to all wishes and expectations of his departmental commander, he notified Johnston that, “threatened by a superior force of the enemy in front and finding it impossible to cross the river, I have to make the fight on the ground I now occupy.” Johnston had not wanted him to make a fight at all.

Then Crittenden found that not only was he unable to retreat across the river to Mill Springs because of lack of boats, he could not even fight on the ground he occupied. Beech Grove was an unfit position in which to resist a determined attack. With no engineering help available to him, Zollicoffer had selected a site commanded by surrounding heights and one from which artillery could not work well against advancing infantry.

Crittenden called a hurried conference of his senior officers on Friday evening, the 17th, and proposed to beat Thomas to the attack. A majority of the senior officers apparently agreed, although as the men readied their weapons and other gear, camp scuttlebutt had it that Zollicoffer and others had opposed the plan. Saturday evening, having learned by then that Thomas was separated from the units in his rear and also, Crittenden hoped, from Schoepf, the Confederate commander called another council of war.

At this meeting “it was determined, without dissent, to march out and attack the enemy . . . the next morning.” That meant they had to depart Beech Grove at once, and they did. At midnight, Crittenden got his whole force moving northward into a “night . . . dark and cold,” with bitter winds driving sleet and rain in the soldiers’ faces. They were on the road to Logan’s taking Thomas’s bait, if that was what it was.

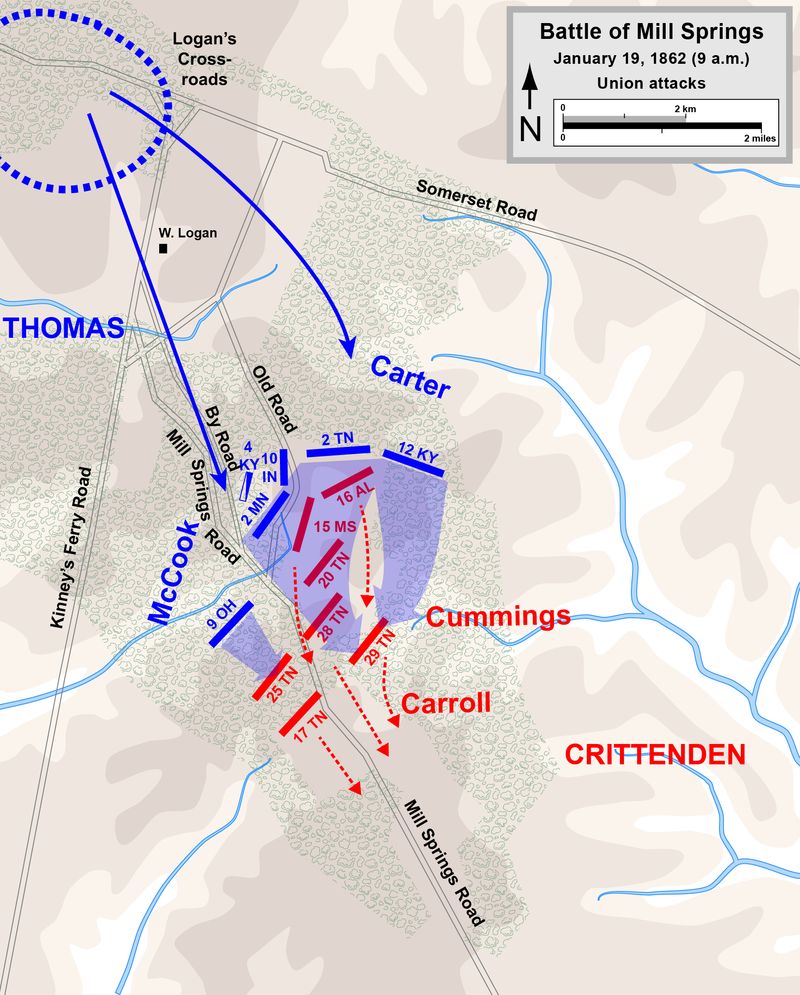

Zollicoffer’s brigade of soldiers from Mississippi and Tennessee and four cannon took the lead. They were followed by three Tennessee regiments plus two cannon commanded by Captain McClung, all of which comprised another brigade under Brig. Gen. W. H. Carroll. Behind these toiled the reserve, an Alabama regiment plus cavalry battalions commanded by Lt. Cols. Branner and McClellan.

The rain-drowned road was more like a canal; in places, the mud and water were more than a foot deep. It took Crittenden’s little army six hours to wade the nine miles to where Thomas’s cavalry pickets waited. Not only were the Confederates weary by the time they began arriving, but the forward units were three miles ahead of the rear ones.

Around 6:30 a.m. on January 19, shortly after dawn, Confederate cavalry drove mounted pickets of U.S. Kentucky Cavalry back a quarter-mile to a log house just left of the road, where they met a hot fire. The road continued straight northwestward over small hills and swales for nearly a mile, then forked into a Y at an intersection with the so-called “Old Mill Springs Road.” The latter angled off due north while its newer, parallel successor continued northwestward a quarter-mile or so to the left; both forks led toward the camps of the Federal regiments. Between the Confederates and the Y were two low, round ridges divided by the road into two fields. At the first ridge’s foot stood another log house that soon became a bloody Confederate hospital.

The battle along the Mill Springs road just south of the forks would be a three-and-one-half-hour slugfest revealing weaknesses that would dog Confederates in the West for the rest of the war. The worst involved weaponry. Despite efforts by Governor Harris to collect workable guns from civilians the previous fall, many of the Tennessee Confederates were armed with aged flintlock muskets yet to be converted to percussion-caps and thus requiring priming powder that was difficult to keep dry. And some of the men were recruits so raw that they had been assigned to their unit just a day earlier and knew almost nothing of drills and commands.

But they could fight. A company of Mississippi skirmishers moved to the left of the road and, amid hot fire, drove pickets of the Tenth Indiana out of another log cabin and adjoining woods at the foot of the second ridge. The Mississippians then crossed the road to rejoin their regiment, while behind them, staying on and to the left of the road, came the Nineteenth Tennessee driving straight ahead, double-quicking across the field and into the woods. There they met and drove backward the main body of the Tenth Indiana. The Confederate attack almost reached the forks of the road and came near overrunning the horses of the Federal cavalrymen, who were desperately fighting on foot at the Indianans’ right rear.

Thomas, roused from his headquarters bed, reached the field about the time his Second Brigade commander, M. D. Manson, sent in the Fourth Kentucky to reinforce the reeling Tenth Indiana. The Hoosiers, commanded by Lt. Col. William Kise, had been “thinned and mutilated,” but they had stemmed the Confederate tide alone for almost an hour. The Fourth Kentucky now steadied the Union left by opening a “deadly fire” into the ranks of the Fifteenth Mississippi.

The Kentucky Federals then charged out of the trees into the hill-crowned field east of the road. Broken by a fence bordering the “Old Mill Springs” fork—the right arm of the Y—and then a creek bed running nearly parallel to the fence, this field hosted a struggle that “became very warm,” reported Col. Speed Fry of the Federal Fourth Kentucky Infantry. The Confederates used the creek bed for cover to move their troops onto the Fourth Kentucky’s right flank, which had been left naked when the Tenth Indiana fell back under the assault by the Fifteenth Mississippi and the Nineteenth Tennessee.

The Mississippians now rose out of the depression just enough to deliver galling fire at close range, and Col. Fry thought the Southerners’ use of the stream bed so unfair that he rashly climbed onto the fence, “denounced them as dastards, and defied them to stand up on their feet and come forward like men,” according to a postwar account. Fry did not stay on the fence long. Having first ordered his men past it, he now commanded them to retreat behind it for cover. There they weathered two charges by the Mississippians, who came forward, he reported, with “bayonets fixed and their large cane knives unsheathed.”

The day, which had dawned soggy and sullen, had become further clouded by gunsmoke that “was beaten back by the rain and, settling on the ground, increased the gloom,” according to a Confederate soldier from Tennessee. When the Fifteenth Mississippi encountered the Kentucky Federals, Lt. Col. Edward C. Walthall apparently remembered a warning by Crittenden in the council of war the night before. Because many of the Confederates wore blue uniforms at this early stage of the war, Crittenden had noted the danger of firing into friendly forces. To prevent this, the Southerners adopted an unfortunate password: “Kentucky.”

Walthall’s skirmishers now reported that they thought the troops in front of them were the Confederate Twentieth Tennessee, which had been following them but presently were being deployed to the right. Walthall had his men lie down while he went to a high point and shouted to his front: “What troops are those?”

“Kentucky,” somebody shouted back.

“Who are you?” Walthall yelled, apparently wanting a unit number.

The reply he got was the same as before, so he ordered the unfurling of a Confederate flag. The banner immediately received a volley of shots, which riddled its folds and put twenty balls in the body of an accompanying lieutenant.

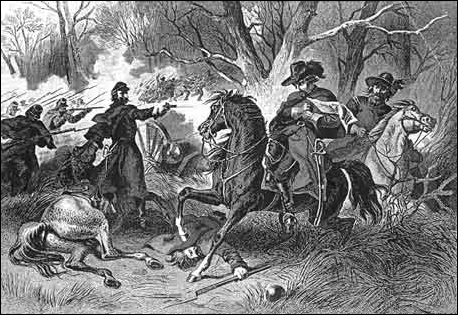

Zollicoffer, probably also mindful of Crittenden’s admonition about friendly fire, soon rode up to Col. Cummings of the Nineteenth Tennessee and ordered him to have his men stop firing. He then moved off to the right of the road and unwittingly approached Col. Fry of the Federal Fourth Kentucky, who had ridden up the side of the ridge to reconnoiter on his unit’s right. Zollicoffer was so close that the two men’s knees touched, but he was also near-sighted and clad in a white raincoat that hid his uniform. He told Fry: “We must not fire on our own men. Those” — waving toward his left — “are our men.”

Fry agreed and was moving back toward his regiment to comply when a Zollicoffer aide rode out of the woods. Seeing that Fry was a Federal, the aide fired, hitting Fry’s horse with a shot that also slightly struck the colonel himself. Fry spurred his wounded animal away and fired a pistol back toward Zollicoffer. Some of the men of the Fourth Kentucky fired, too.

Zollicoffer was struck by a ball from a pistol and two more from muskets, one of the shots striking his heart. He died immediately, perhaps in the process of realizing his mistake. The Nineteenth Tennessee, having been ordered not to fire, had to endure a dismaying fusillade from the Union soldiers in the Fourth Kentucky.

The Mississippians under Walthall, unhampered by any no-fire order, charged and nearly broke Fry’s right. Then Thomas sent the Tenth Indiana back to retake the position it had first occupied to the right of Fry. News of Zollicoffer’s death spread fast, and in the interval in which the Nineteenth Tennessee stopped firing, the Confederate drive stalled. A subsequent general advance by Carroll’s supporting brigade could not regain the Confederate momentum.

The fight was hardest along the fence row where for a full hour, according to Crittenden, the Fifteenth Mississippi tried to drive between Kise’s Hoosiers and Fry’s Kentuckians. By the time the Tenth Indiana got back to the fence on its return to the field, it found “many of the enemy . . . lingering” there. Kise later wrote that these were “bayoneted by my men between the rails.”

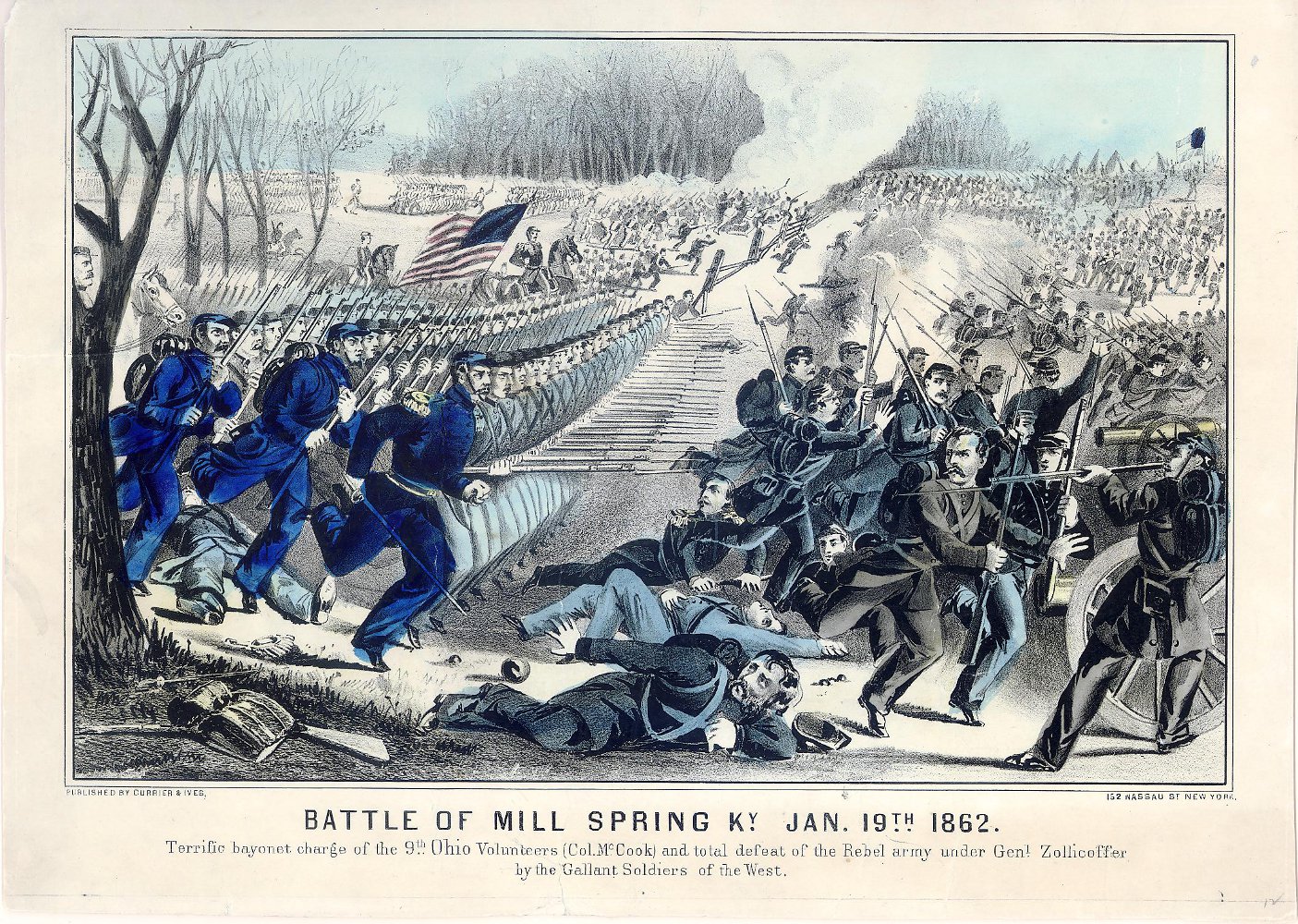

To reinforce Kise and Fry, who now were almost out of ammunition, Thomas ordered up the Second Minnesota and the so-called Bully Dutchmen of the Ninth Ohio, who already had seen action in western Virginia. The Dutchmen went in on the Federal right, while the Minnesotans took over for Kise and Fry. The Second Minnesota’s right ended up “about 10 feet from the enemy” at the fence, where the fighting was virtually hand-to-hand.

Confederates and Federals “pok[ed] their guns through the same fence,” reported the Ninth Ohio’s Colonel Robert McCook. The Minnesotans and Mississippians repeatedly assaulted each other for control of the fence, but the Ninth Ohio’s charge on the Union right stopped the Confederate flanking attempt, and the Southerners “retired in good order to some rail piles, hastily thrown together, the point from which they had advanced upon the Fourth Kentucky,” McCook wrote.

On the other end of his line, Thomas had sent Samuel P. Carter’s Tennessee Brigade to smother a bid by the Confederate Twentieth Tennessee to turn the Union left. With both their wings overlapped and the enemy’s center reinforced, the Confederates began to give ground, getting beaten by not only superior generalship but by luck and greater firepower.

Carroll’s regiments came in as reinforcements and vainly tried to dam the rising Federal tide, but under the Union counterattack the Twenty-eighth Tennessee, backing up the Confederate center, “broke and fled in confusion from the field,” Carroll later reported. The Twenty-ninth Tennessee behind them also “fell back in considerable disorder and could not be induced to face the enemy again.”

Carroll later indicated in his battle report that he hardly blamed either unit: “The repulse of the regiments of my command that gave way in confusion during the battle is attributed, in a great measure, to the inefficient and worthless character of their arms, being old flint-lock muskets and country rifles, nearly half of which would not fire at all. I saw numbers of men walking deliberately away from the field of action for no other reason than [that] their guns were wholly useless.”

A member of the Nineteenth Tennessee wrote that he saw “two or three of the boys break their guns over the fence after several attempts to fire them.” In the Twentieth Tennessee, another soldier recalled that “one-third of the arms of the Confederates” were “useless,” and many that did work operated so poorly in the rain that they were able to be fired no more than a dozen times throughout the battle.

With Crittenden’s counterattack foiled, his lead units, the Fifteenth Mississippi and Nineteenth Tennessee, fell back in the face of a mid-morning Federal counterthrust and Southerners now streamed from the field. A retreat to Beech Grove was ordered, but “it did not take much ordering,” W. J. McMurray of the Twentieth Tennessee would remember. Confederate doctor W. J. Worsham recalled that during the battle he “picked up a Yankee overcoat and put it on in the cold rain,” only to remove it and throw it over the wet ground for a mortally wounded comrade to die on as “the whole line” gave way.

Men left the battlefield “in wild confusion and disorder.” Dr. Worsham remembered trying to help the wounded as much as possible in the fear-filled rush to avoid capture. He helped carry Charley Clemenson of the Nineteenth’s Company E in a blanket into the yard of the cabin used as a field hospital, but by then fellow Confederates “were hurrying by as rapidly as they could, the road and the woods . . . full” of comrades “in hot haste to be gone.”

“Poor Charley was dying when we laid him down. We can never forget the sad anxious expression of his face as we left him . . . dying alone, deserted by all whom he thought were friends, left on the cold ground with naught but the cold rain to wash the sweat of death from his brow.”

* * *

The Confederates retreated back down the Mill Springs road. It had taken them six hours to travel it before dawn, but they now made better time, leaving behind one mired cannon and an appalling litter of haversacks.

The Federals pursued, but with a deliberateness that would come to be regarded as characteristic of Thomas in this war. The heavy mud was one reason for their measured pace. Another was that many of them, having entered the fight without breakfast, continually stopped to rifle the discarded Confederate packs and sample the contents: bacon as well as cornmeal ground by the facility for which Mill Springs was named. It was late afternoon before Thomas’s lead elements reached Beech Grove and started shelling its fortifications.

Almost as soon as night fell, Crittenden began ferrying his men across the Cumberland on what was virtually their sole conveyance, the small steamboat Noble Ellis. He managed to get the men out, but that was all. Next morning, the Fourteenth Ohio and Tenth Kentucky moved forward to lead an assault and found Beech Grove deserted. At the ferry crossing below the bluff they discovered a crush of eleven artillery pieces, more than 150 wagons, and a thousand horses and mules. Even the steep road up the far bank was strewn with baggage, and the Noble Ellis had been set afire and sunk.

“General, why didn’t you send in a demand for surrender last night?” Col. Fry asked Thomas, noting all the evidence of Confederate panic. The Union commander looked up, hesitated, and then admitted a mental lapse.

“Hang it, Fry,” he said. “I never once thought of it.”

On the Cumberland’s opposite bank began the hardest march the Nineteenth Tennessee’s Worsham “experienced during the four years of war.”

McMurray of the Twentieth recalled “a long journey, hitherto unparalleled,” through the “rough, barren, and unfriendly country” of the Cumberland Mountains. The first night, they stopped a mile southwest of Monticello, Kentucky, pitching no tent “for we had none; neither had we blankets on which to lie . . . Having had nothing to eat all day long, we lay down with empty stomachs to dream of the plenty we had left in camp. The next morning we had issued to us an ear of corn to each man (as if we were horses) to parch for breakfast” over “fires which were very poor for want of [dry] wood.”

Worsham wrote that they lived on this parched corn “almost the entire ten days” of their frantic, hundred-mile straggle from Mill Springs to Gainesboro, Tennessee.

Many miles west at Bowling Green, the Confederate western high command recognized Logan’s Crossroads and the flight from Mill Springs for what they truly constituted: disaster. Johnston’s first intimations of it, because of the remote area’s scant communications, were from accounts in newspapers from Louisville. After reading them, he wrote Richmond, “If my right is thus broken as stated, East Tennessee is wide open to invasion—or, if the plan of the enemy be a combined movement upon Nashville, it is in jeopardy . . .”

Official tallies would eventually show that the Confederates lost 125 men killed and 404 wounded or missing out of the 6000 or so engaged. The Federal forces lost 39 killed and 207 wounded from their 4400 men. It was a small engagement relative to many larger fights during the war, and the nation’s attention would shift to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s stunning victories weeks later at Fort Henry and then Fort Donelson.

But Johnson was correct in that the battle at Mill Springs served to break the Confederate line of defense in eastern Kentucky, and led to the fall of Nashville on February 25, 1862. Abraham Lincoln’s goal of pushing south through areas of eastern Kentucky and Tennessee sympathetic to the Union would prove to be sound.