The Army has named ten military bases in honor of men who killed 365,000 U.S. soldiers. Should they be renamed? Or left as they are, since the bases are part of a “great American heritage," as Mr. Trump says?

-

June 2020

Volume65Issue3

For the duration of the Civil War, General Ulysses S. Grant rode on the same Grimsley saddle over countless battlefields, witnessing the deaths of thousands of men who fought to end slavery and preserve the United States against dissolution.

Grant’s saddle, and the ambulance wagon that carried his baggage, are two of many treasures in the U.S. Army Quartermaster’s Museum at Fort Lee in Virginia. That base houses the command that supplies the Army around the world, and develops the strategies and training to sustain it.

The Army doesn't think so, at present. “Every Army installation is named for a soldier who holds a place in our military history,” Gen. Malcolm Frost, the service’s top spokesman, told TIME Magazine. “Accordingly, these historic names represent individuals, not causes or ideologies. It should be noted that the naming occurred in the spirit of reconciliation, not division.”

President Trump agrees. “It has been suggested that we should rename as many as 10 of our Legendary Military Bases," he tweeted recently. "These Monumental and very Powerful Bases have become part of a Great American Heritage, and a history of Winning, Victory, and Freedom.”

But many historians feel differently. "Removing the names of Confederate generals from American military bases is long overdue,” says Peter Cozzens, author of six books on the Civil War. “As West Point graduates, these men were traitors pure and simple.

“Apart from that, at least two of those for whom forts were named--Braxton Bragg and Leonidas Polk were mediocre generals at best,” he notes. “Surely it would be better to honor truly great American generals of later generations such as John J. Pershing and Omar Bradley instead."

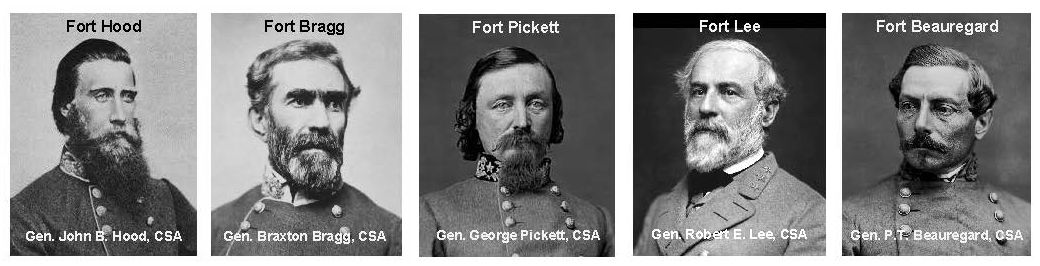

Here are short bios of the 10 Confederate leaders honored by the Army with base names:

1. General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard

P.T. Beauregard is the general who started it all, the first named a general in the Confederate Army and the officer who ordered rebel troops to fire on the American flag.

Beauregard was born into a French Creole family on a plantation in Louisiana, graduated second in his class at West Point in 1838, and fought with distinction in the Mexican War.

Confederate President Davis put him in command of the defense of Charleston, and on April 12, 1861, Gen. Beauregard gave the order for South Carolina troops to fire on Fort Sumter, which happened to be commanded by his former instructor at West Point, Captain Robert Anderson. Ever the gentleman, Beauregard sent his former instructor some cigars days before opening fire.

Beauregard was then ordered to Richmond and placed in charge of the city's defenses. He led the rebel troops at the Battle of Bull Run who crushed the Federal army commanded by his West Point classmate, Gen. Irwin McDowell.

Camp Beauregard is a U.S. Army installation in central Louisiana now operated by the Louisiana National Guard. It was created in 1917 at a time when the War Department authorized the building of more than thirty camps around the country to train troops for World War I.

The Camp was also the base for the huge Louisiana Maneuvers before the outbreak of World War II that were a primary training effort to get the Army ready to fight.

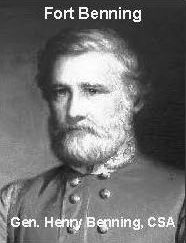

2. General Henry L. Benning

Henry L. Benning was an ardent secessionist even before war erupted between the North and South, opposing abolition and the emancipation of slaves as an associate justice of the Georgia Supreme Court in the 1850s. He called for a consolidated south that would "put slavery under the control of those most interested in it," and took an active part in the state convention that voted to secede from the Union following the election of President Abraham Lincoln in 1860. He was even considered for cabinet position in the new Confederacy, but instead chose to join the army, becoming colonel of a Georgia infantry that he raised himself.

Henry L. Benning was an ardent secessionist even before war erupted between the North and South, opposing abolition and the emancipation of slaves as an associate justice of the Georgia Supreme Court in the 1850s. He called for a consolidated south that would "put slavery under the control of those most interested in it," and took an active part in the state convention that voted to secede from the Union following the election of President Abraham Lincoln in 1860. He was even considered for cabinet position in the new Confederacy, but instead chose to join the army, becoming colonel of a Georgia infantry that he raised himself.

As a soldier, Benning -- called "Old Rock" by his men -- opposed military conscription and was nearly court-martialed for refusing to obey orders. He spent much of the war as a brigade commander under Texas' John Bell Hood, participating in bloody battles at Gettysburg and Chickamauga.

Fort Benning, near Columbus, Georgia, was named after the Confederate general in 1918. It served as a basic training site and home of the army's Infantry throughout much of World War II. Today it houses the United States Army Maneuver Center of Excellence, the United States Army Armor School, and the United States Army Infantry School, among others.

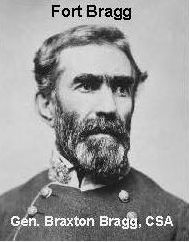

3. General Braxton Bragg

Born in North Carolina, Braxton Bragg was a career military official who attended West Point, fought in the Second Seminole War in Florida and in the Mexican-American War in Texas. He resigned from the army in 1856, becoming a sugar planter and slave owner in Louisiana, but joined the Confederate Army in the Civil War, during which he commanded the legendary Army of Mississippi, later known as the Army of Tennessee.

Despite his extensive military experience, however, Bragg is usually ranked among the worst Confederate generals. Though he won one of the most significant Confederate victories at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863, he lost most of his other battles, including a stunning defeat at Chattanooga two months later at the hands of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

Bragg served for a period as a top advisor to his friend President Jefferson Davis, but was replaced after the promotion of General Robert E. Lee. Bragg was generally despised by his men, who saw him as overly regimented and quick-tempered.

Fort Bragg was created in 1918 as an artillery training base, and named for North Carolina native Bragg. It is now the largest military installation in the world with more than 50,000 active duty personnel. The base maintains two airfields, the U.S. Army Forces Command, and the Womack Army Medical Center, among others.

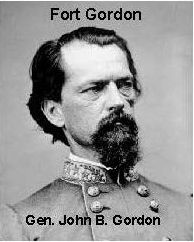

4. General John Brown Gordon

Born in 1832 to a prominent minister in Georgia, John Brown Gordon entered the Civil War with little military experience or education. But he quickly established himself as a capable leader, first as captain of a mountaineer company known as the “Raccoon Roughs" and later as colonel of the 6th Alabama Regiment. He also served as a lieutenant general under General Robert E. Lee, and was present at many major battles of the war, including First Bull Run, Seven Pines, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg.

Following the war, Gordon returned to his home state and began a career in politics. As both governor of Georgia and a member of the U.S. Senate, he strongly opposed Reconstruction and called for restrictions and the use of violence on freed slaves.

In 1879 he became the first ex-Confederate to preside over the U.S. Senate, where he led support for industrialization and the "New South" movement. Gordon was also rumored to be head of the Klu Klux Klan in Georgia, though his involvement was never confirmed.

In July 1917, after the U.S. entered World War I, the Army established a military installation northeast of Atlanta called Camp Gordon in honor of the Georgia native. The post was renamed Fort Gordon in 1956. Today, Fort Gordon is the home of the United States Army Signal Corps, United States Army Cyber Corps, and Cyber Center of Excellence.

5. General A. P. Hill

Another career military official, Ambrose Powell Hill was born in Virginia and fought both in the Mexican-American War and the Third Seminole War before joining the Confederacy in 1861. He distinguished himself early on as commander of the "Light Division," a group of six battalions that fought under Robert E. Lee in northern Virginia. He also worked closely with General Stonewall Jackson, joining him in battles like Second Bull Run, Antietam, and Fredericksburg.

Another career military official, Ambrose Powell Hill was born in Virginia and fought both in the Mexican-American War and the Third Seminole War before joining the Confederacy in 1861. He distinguished himself early on as commander of the "Light Division," a group of six battalions that fought under Robert E. Lee in northern Virginia. He also worked closely with General Stonewall Jackson, joining him in battles like Second Bull Run, Antietam, and Fredericksburg.

Hill was shot and killed in 1865, on the the last day of the siege of Petersburg. The U.S. Army established Fort A.P. Hill in 1941, outside Bowling Green, Virginia. The base now focuses on arms training and is used by all branches of the US Armed Forces.

6. General John Bell Hood

Though he was born in Kentucky, John Bell Hood spent many years in Texas, where he joined the U.S. Army and fought in several western conflicts. The Civil War compelled him to consider Texas as his adopted home, since his native state remained neutral. He joined the Confederate army in Texas as a cavalry captain, and quickly climbed the ranks to major and then lieutenant general.

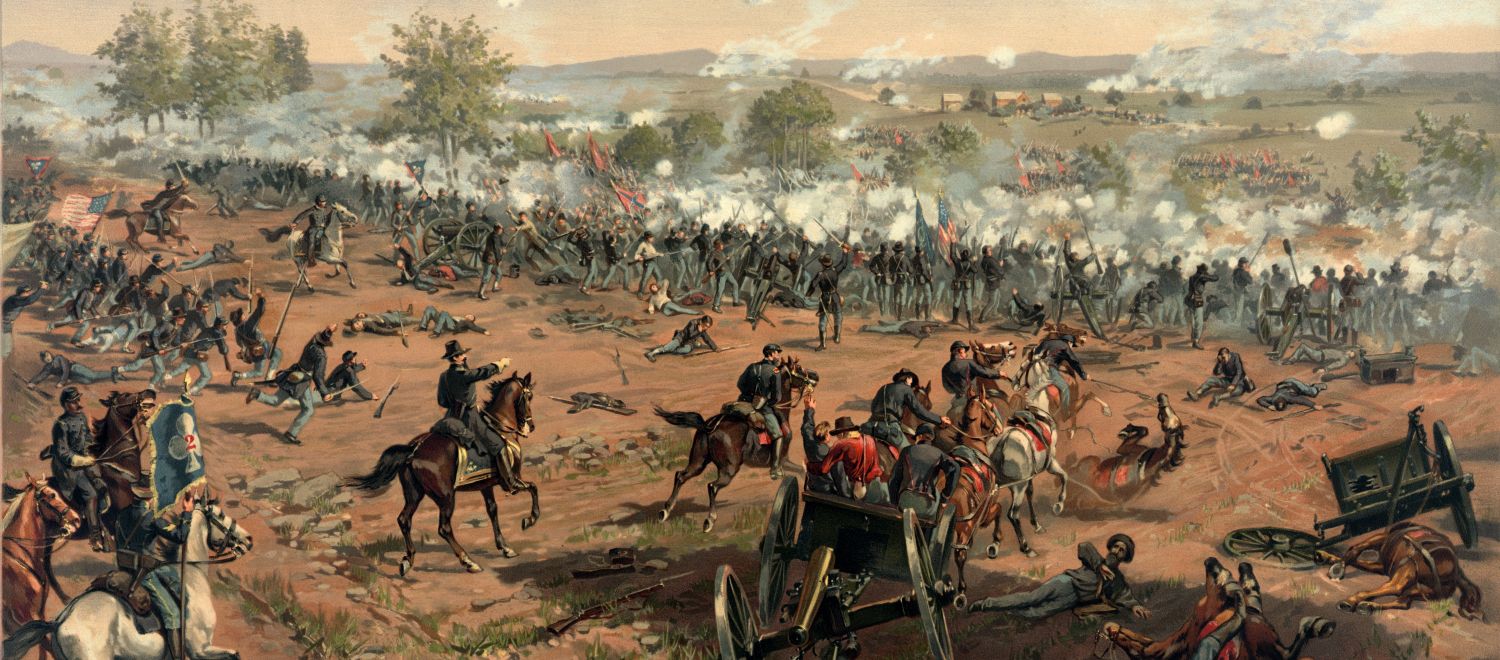

Hood is considered one of the boldest -- and sometimes most reckless -- Confederate commanders. He played a pivotal role at the Battle of Gettysburg, where he followed a daring order to attack the Union’s left flank. He lost a leg at the battle of Chickamauga, and launched several other bloody offensives -- including in Atlanta, Franklin, and Nashville -- before being relieved of his rank in 1865. He later died of yellow fever.

The U.S. Army established Fort Hood in Killeen, Texas during World War II to test and train tank destroyers designed to be used against German armored units. Today, it is headquarters of III Corps and First Army Division West and home to the 1st Cavalry Division and 3rd Cavalry Regiment, among other units.

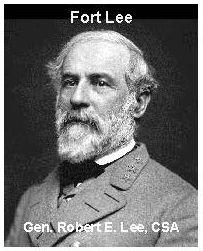

7. General Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee agonized longer than most people realize over whether to take up arms against his country, as historian Elizabeth Brown Pryor reported in American Heritage after reviewing his recently discovered personal papers. Yet he ultimately disavowed his oath to defend the Constitution and joined the Confederate cause, choosing to defend his native Virginia.

Lee commanded Confederate forces in at least 14 major engagements in the Civil War, from Cheat Mountain in September 1861 to Seven Days, Second Manassas, Antietam, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Wilderness, Sp Appomattox.

These bloody fights cost the U.S. Army a staggering 165,000 casualties.

Gen. Lee is honored at Fort Lee in Virginia, a major military facility and headquarters of the Army's Combined Arms Support Command, the Quartermaster, Transportation, and Ordnance Schools, the Army Logistics University, and other important facilities. It also houses two Army museums, the Quartermaster Museum and the Army Women's Museum.

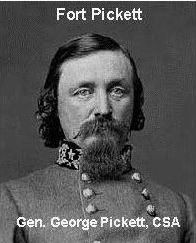

8. General George Pickett

A native of Virginia, George Pickett spent his pre-Confederacy years as an Army officer, serving as a second lieutenant in the Mexican–American War and captain in the so-called Pig War in Washington Territory. He attended the U.S. Military Academy, where he graduated last out of 59 cadets in the class of 1846.

In the Confederate Army, Pickett participate in numerous battles and skirmishes, often as a major general under General James Longstreet. But he's perhaps best remembered for Pickett's Charge, a bloody Confederate attack on the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg that killed and wounded 23,000 soldiers and half the Confederate Army's forces. The stinging defeat ended General Robert E. Lee's campaign in Pennsylvania and greatly demoralized the Confederacy as a whole. At one point in the war, Pickett also ordered the hanging of 22 army deserters, then fled to Canada following the Confederacy's defeat out of fear of prosecution.

In 1941, near Blackstone, Virginia, the U.S. Army established what would later be named Fort Pickett. The base is now home of the Army National Guard Maneuver Training Center.

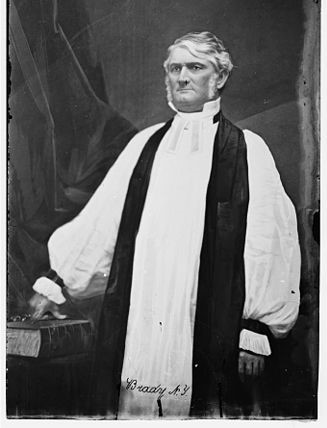

9. General and Reverend Leonidas Polk

A slaving-owning planter from Tennessee and the second cousin of President James K. Polk, Leonidas Polk was another Confederate commander who entered the fray with little formal military experience. Polk was a bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana when war broke out, at which point he resigned the position and offered his services to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, a friend and former classmate at West Point. He was commissioned a major general in 1861.

Polk is considered by many historians to be one of the worst Confederate generals, owing to his many failures and famed refusal to follow orders. He's credited with losing a crucial strategic asset when he invaded Kentucky in 1861, forcing the then-neutral state to side with the north. He also developed a lasting feud with his commanding officer, General Braxton Bragg, who accused him of insubordination at battles like Perryville and Chickamauga. Polk was killed in action in 1864 when he was struck by a cannonball at Pine Tree.

Established in 1941 near the Kisatchie National Forest, Fort Polk began as a base for a series of military maneuvers in Louisiana during World War II. Today the base is home to the Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC), the 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division, 115th Combat Support Hospital, U.S. Army Garrison and Bayne-Jones Army Community Hospital.

10. General Edmund Rucker

Lesser known than other famous Confederate officers, Edmund Rucker was born in Tennessee and worked as a railroad surveyor and engineer before enlisting as a private under General George Pickett. He served as captain of various Tennessee battalions in 1862 and 1863, and in 1864 was assigned to Forrest's Cavalry Corps in Mississippi and given a brigade under Gen. Abraham Buford. He was present at several major battles over that time, including the battle of Franklin, where he was captured and later had his left arm amputated.

Following the war, Rucker became an industrial leader of Birmingham, Alabama. In 1942, the U.S. Army renamed Ozark Triangular Division Camp, an installation in Dale County, Alabama, Fort Rucker in his honor. The post is the primary flight training installation for U.S. Army Aviators and is home to the United States Army Aviation Center of Excellence (USAACE) and the United States Army Aviation Museum.