The dumping of tons of tea in protest set the stage for the American Revolution and was a window on the culture and attitudes of the time.

-

Spring 2024

Volume69Issue2

Editor's Note: Benjamin L. Carp is a professor of history at Brooklyn College and the author of a definitive book about the Tea Party, Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America and Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution.

In 1820, a 61-year-old Ohio blacksmith with no more than $70 worth of property to his name made a startling admission in court: “I was on board the East India Company’s Ships in the Harbour of Boston and assisted in throwing the tea overboard on the 18th (actually, the 16th) December in the year AD 1773, being then fifteen years of age.”

Joshua Wyeth had just confessed to participating in the Boston Tea Party, which no more than four or five people had previously acknowledged. The “destructors” initially feared arrest for treason, and even after the war, they worried about being sued for damage to property. Wyeth finally felt safe to tell his story almost a half century later. He went on to describe his participation in the battles of Bunker Hill, Brooklyn, Harlem Heights, and White Plains. He was attempting to gain a pension from the United States government, which had never adequately rewarded many of its Revolutionary soldiers for their service.

When Wyeth told his story in detail, he talked of the indignation that he and his associates felt about British policies in Boston. Legal tea bore a tax or duty imposed by Parliament in the Townshend Acts in 1767. To protest these acts, many American merchants had agreed with one another not to import British goods, so as to put pressure on British merchants. The challenge was that the agreements had to be universal in order to be effective.

By 1770, New York City and Philadelphia had reduced their legal tea imports to nearly zero. Colonists still drank tea, but they switched to smuggled tea from continental Europe. However, in Boston, while smugglers were doing some of the importing, plenty of legal tea was still entering the New England market. When the non-importation agreements among colonial merchants collapsed in the summer of 1770, many of the radical patriots in the middle colonies blamed Boston for failing to keep up its end of the bargain. These resentments were still lingering in 1773.

Under the new Tea Act of 1773, the East India Company received a tax break on tea shipped to America, and was given permission to ship tea directly to America, rather than go through a British or American merchant house. The tax that American colonists paid for their tea remained on the books, but they’d be facing an East India Company monopoly, as well as the tax.

Joshua Wyeth remembered the turning point in November 1773: “Our indignation was increased” by the arrival of three merchant ships bearing 340 chests of tea belonging to the East India Company and designated for sale in Boston and throughout New England. A fourth ship was on its way to Boston, but it ran ashore on Cape Cod. Three more ships headed to New York City, Philadelphia, and Charleston.

In all four of these seaports, the Sons of Liberty wanted this tea sent back to London. But it wasn’t so simple. The tea consignees (agents) weren’t enthusiastic about giving up their generous new commissions. Shipowners couldn’t just turn their ships around with dutiable goods aboard, without having their cargo seized. But in New York and Philadelphia, radicals were able to pressure the agents, the shipowners, and local officials into sending the tea back to London. In Boston, however, the agents refused to cave. And the customs officers and the governor refused to look the other way and let the ships turn around.

Wyeth explained, “We agreed, that, if the tea was landed, the people could not stand the temptation, and would certainly buy it.” In other words, even though the Tea Act would mean cheaper tea for the colonists, radicals argued that this was just a way to seduce the colonists into paying taxes for which they had not given consent.

Meanwhile, writers in New York and Philadelphia were warning Americans what would happen if they allowed the tea to land. One man named “Hampden,” who may have been the New York patriot Alexander McDougall, argued that the East India Company’s monopoly on the East India trade was corrupting Great Britain’s politics and constitution: “The Purchase of the Company’s Iniquities, Tea, must be sent to the Colonies, the Profit of which is to support the Tyranny . . . in the East, and enslave the West.” The colonists were aware that the company’s abusive practices in Bengal had caused a severe famine a few years before. By ceding Parliament’s right to tax the colonies without their consent, and by welcoming the East India Company into their midst, the Americans would wind up no better than these “helpless Asiaticks.”

Others added that, if Americans accepted a monopoly on tea, further monopolies were sure to follow. John Dickinson, the author of Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania and a future signer of U.S. Constitution, argued that, “It is not the paltry Sum of Three Pence which is now demanded, but the Principle upon which it is demanded, that we are contending against.”

The American rebels opposed the monopoly of the East India Company and the Revenue Act, which amounted to taxation without representation. It was also personal. Two of the agents that the company picked to receive the tea were sons of the hated Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

Benjamin Franklin got in a bit of hot water by making a few of the royal governor’s letters public in 1773, including one that urged the British government to manage Boston with a firm hand, even if it required “an abridgment of what are called English liberties.” Parliament had decided to begin paying Hutchinson and other civil officers from the money that the tea duty and other unpopular taxes raised.

In other words, it wasn’t just the tax, but the fact that this tax money was going into the pockets of a hated enemy, while the profits were earned by Governor Hutchison’s sons. In other words, American taxes would be used to support the very tyrants who were trying to oppress them.

On December 16, 1773, at a crowded meeting in the Old South Meeting House, the largest church in Boston, a leather-dresser named Adam Collson supposedly shouted, “Boston Harbor a tea-pot this night!” Then, he and his companions marched down to the water’s edge at Griffin’s Wharf and staged an act of rebellion that would have worldwide significance.

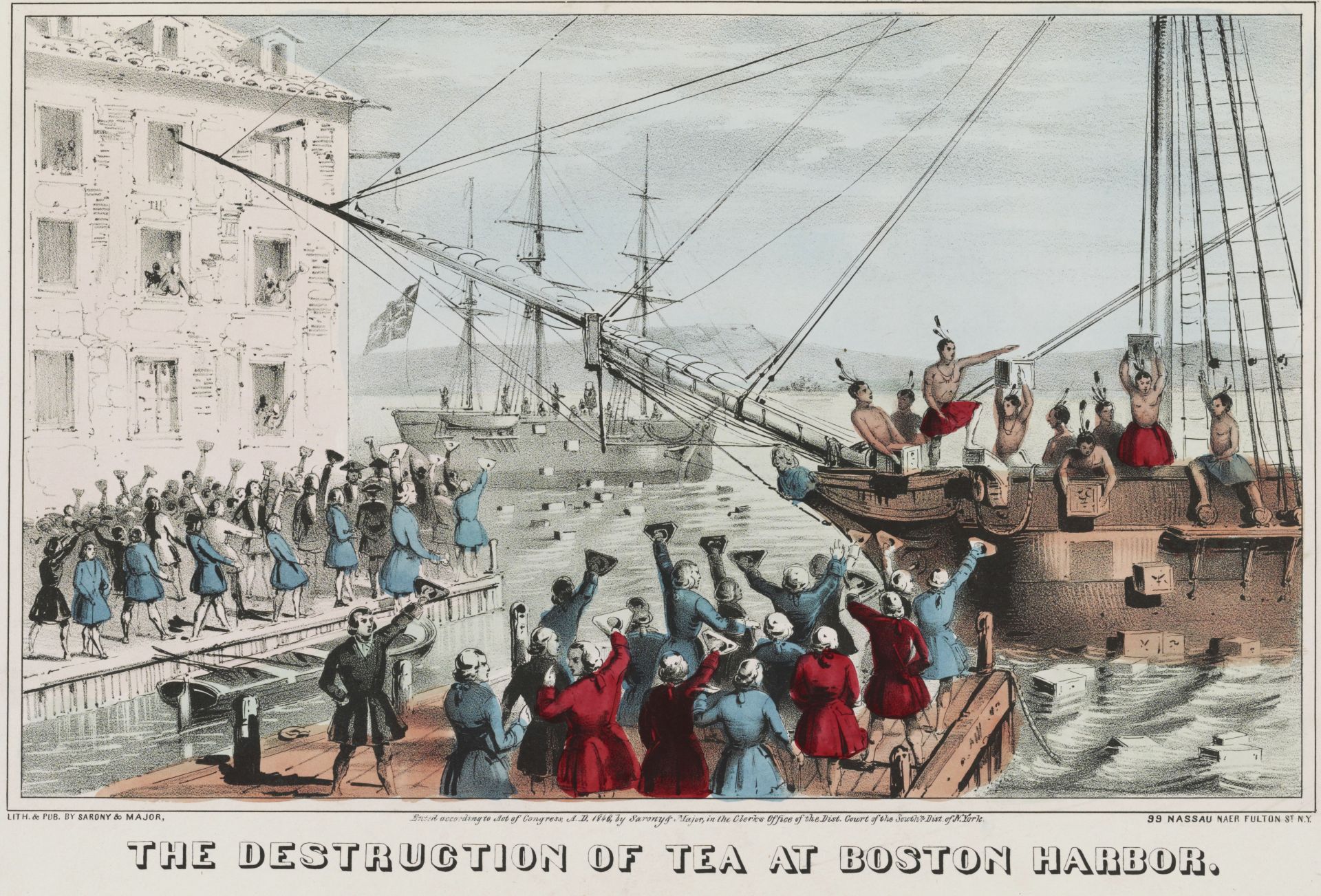

“At the appointed time, we all met according to agreement,” recalled Joshua Wyeth. “We were dressed to resemble Indians, as much as possible. We had smeared our faces with grease, and soot, or lampblack. We should not have known each other, except by our voices, and we surely resembled devils from the bottomless pit, rather than men.”

After placing sentries on the wharves and nearby ships, about a hundred men boarded the three trading ships docked at Griffin’s Wharf. The ships, which had arrived in the previous weeks from London, were named the Dartmouth, for an aspiring port town; the Eleanor, for a woman; and the Beaver, in homage to New England’s industrious work ethic.

The men “proceeded readily to business,” and ordered the crew to open the hatchways. Then, they jumped into the holds and attached pulleys and ropes to the tea chests. They hoisted the chests up to the decks, smashed them open with axes, carried them to the railings, and dumped the contents overboard.

All together, they destroyed 340 chests with more than 46 tons of tea, dumping it into the dark waters of the harbor. (At that time, a single ton of tea was worth enough to have bought Paul Revere’s house in the North End.) The intoxicating, bittersweet aroma of the tea filled the air, and at least one man, Charles Conner, was so unable to resist it that he stuffed some of the leaves into his pockets. The rest of the men remembered that there were principles at stake and gave Conner “a severe bruising” for his violation. The riot was done in two or three hours.

“We stirred briskly in the business,” Wyeth wrote, “from the moment we left our dressing room. We were merry in an under tone at the idea of making so large a cup of tea for the fishes, but were as still as the nature of the case would admit….I never labored harder in my life.”

The tea-destroyers hailed from all walks of life. Men with strong backs and hard Yankee accents, they were a mix of young merchants, craftsmen, apprentices, and workers. That evening of December 16, they spoke for all the dissidents in Boston who had squared off against the policies of the British government. The Boston Tea Party wasn’t a formal rebellion, per se, or even a protest against the king — but it set in motion a series of events that led to open revolt against the British Crown. The destruction of the tea, which only became known as “The Boston Tea Party” 50 years later, was a bold, defiant act of political mobilization.

These rebels had carefully calculated their reasons for dumping the tea that evening. They needed to destroy it before the stroke of midnight. If they didn’t act by that time, the hated customs officers would seize the tea and make it available for sale. The rebels would have preferred to force the captains of the three ships to just leave Boston harbor and take the tea back to London. But, when the ships’ owners proved reluctant to do so, the men decided they had no other choice but to destroy the tea.

Why did the destroyers of the tea want to prevent it from landing in Boston? The easiest answer is that Parliament had imposed a tax on tea. Some local people thought this tax was reasonable, but a dissident faction of Bostonians (the majority of the townspeople, in fact) believed that Parliament had no right to raise revenue from American colonists, without the colonists’ consent.

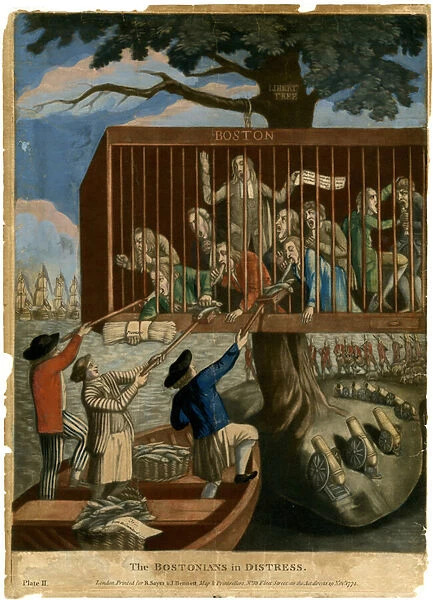

The Bostonians worried that more taxes were on the way. They knew that the revenue from the taxes paid the salaries of the civil officials who the British government had appointed to enforce the imposition of taxes. To the Bostonians — and other rebellious souls throughout the colonies — this was a blatant example of tyranny.

Even worse, this tea would have been sold by the preferred agents of a monopoly company, the British East India Company. Parliament had imposed this new arrangement under the Tea Act, which now threatened American merchants by cutting them out of the tea trade. If Parliament could sell tea to America this way and earn revenue from the sales, then the British government could start creating new monopolies on the sale of other products. Exorbitant prices, mammoth monopolies, and crushing taxes might leave Americans with nothing.

The Sons of Liberty and their allies were frightened, not just because of what they saw happening in Boston, but because of what they had seen happening abroad, with tyranny and liberty often locked in struggle. The Boston Tea Party was not just a local phenomenon, but a global one: the British East India Company, which was gaining territorial control over more and more of Bengal (and other parts of what is now India), made much of its profit selling tea, a product grown by the Chinese.

The Boston Tea Party had revolutionary significance — it set the stage for an American rebellion and the war that followed. The Tea Party was an expression of political ideology about taxes, rights, and authority. Just as important, it was a window onto American culture and society. Americans’ consumer habits, including their love of tea, played a role in the way the resistance unfolded. White Americans’ fear and admiration of Indians, as well as their condescension toward them, help us to understand the disguises that the tea-trashers wore. Boston’s colonial legacy of riotous parades, angry protest, and political organization provided the ingredients that made the Tea Party possible.

The destruction of the tea was a quintessential rejection of corporate and government authority that became a cherished American tradition. The Tea Party involved a relatively broad segment of the population, even though this was an era when only the elite were thought fit to rule and make decisions. Because of this, the destruction set a world standard for future democratic protest.

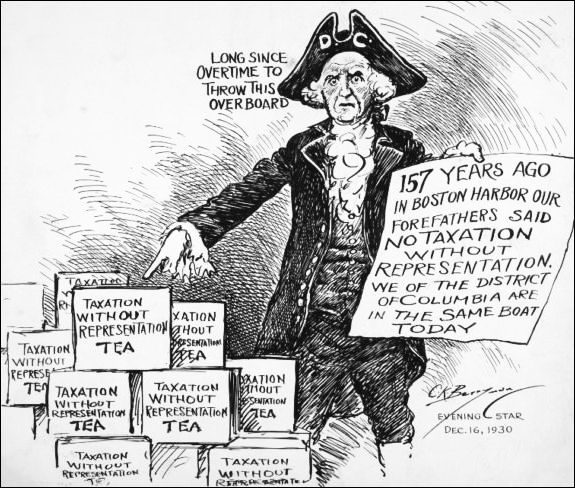

From the perspective of King George III and his ministers, the Boston Tea Party was the culmination of a decade’s worth of flawed imperial policy. To most white Americans, the Tea Party became an emblem of their faith that a determined and organized group can accomplish momentous political change, culminating in independence. The participants were men who showed their willingness to defy the law in defense of their rights. To this day, journalists, pundits, and politicians frequently cite the Tea Party as the first and most famous example of Americans’ heritage of civil disobedience, their penchant for secret conspiracies, and their aversion to foreign-trade restrictions, excessive taxation, and government overreach.

By reading the tea leaves at the bottom of Boston harbor, we can see the American character itself taking shape.

The day after this act of rowdy rebellion, the attorney and future president John Adams called it “the most magnificent Movement of all …There is a Dignity, a Majesty, a Sublimity, in this last Effort of the Patriots, that I greatly admire.” Not everyone agreed. Some found the Tea Party to be inspiring and democratic, but others called it riotous, disorderly, and disturbing. They saw a pack of rebels who had disobeyed the law, destroyed private property, and threatened anyone who stood in their way.

Eighteenth-century Boston was a town in which violent crowd action was not uncommon: from time to time, townspeople pulled down opponents’ houses, brawled with soldiers, threw bricks at officials, tarred and feathered opponents, and otherwise asserted their power. In this climate, the tea consignees and senior customs officials had feared for their lives to such a degree that they fled to Castle Island offshore. By December 16, 1773, Bostonians topped it all off with the invasion and destruction of private property. The kind of political movement that gave birth to the Tea Party protest — and the Revolution — seems both exciting and extreme.

Throughout history, the Boston Tea Party has been interpreted and used in different ways. In part, because it involved no bloodshed, it became a formative expression of liberty, independence, and civil disobedience, representing the finest human tradition of non-violent resistance to tyranny. The Tea Party was sublime, in John Adams’s words, because it was a rejection of arbitrary rule. The protest is also stirring in its radical potential for mobilizing people from all walks of life. Most people can’t imagine themselves in knee breeches signing the Declaration of Independence, but they can easily imagine destroying the East India Company’s tea.

The Boston Tea Party has thrilling and also frightening implications for us today. It justifies taking action on behalf of fundamental rights in defiance of the law; but turn it around and it might also justify the bullying nullification of any law or state of affairs that an outspoken group dislikes. Americans have invoked the Boston Tea Party to combat slavery, damage to the environment, racial discrimination, legal abortion, court-ordered busing, taxation, and illegal immigration. The Tea Party opens up a Pandora’s box — out comes chaos, but also hope. In this way, it exemplifies an ongoing struggle in America between law and order and democratic protest.

Perhaps we should not be too quick to embrace the Boston Tea Party — which falls under the FBI's definition of terrorism (destroying property to influence policy) — as a simple, uplifting tale of American origins. Americans enshrine their traditions of democratic protest, but they also profess to respect law and order, and our regard for the Boston Tea Party stands at the frontier of these two values.

The Boston Tea Party remains a defining historical event, not just because it brought about dramatic change in its time, but because it has resonated in history ever since. Extremists and activists from the Klan to pro-temperance and anti-temperance advocates, women’s suffragists, and marijuana activists have cited the Tea Party as inspiration.

In any case, after 250 years, the Tea Party continues to resonate as a seminal event in American history.