In 1942, over a quarter of a million ordinary citizens volunteered to help defend our country as Nazi submarines terrorized the East Coast and Caribbean waters, sinking fuel tankers and cargo ships with near impunity.

-

Spring 2020

Volume65Issue2

The killing machine known as Unterseebooten-507 skulked, undetected, through the murky yellow water at the mouth of the Mississippi River, practically within shouting distance of the Louisiana shore. Six full months after Nazi Germany’s declaration of war against the United States, not a single airplane – military, civilian, or otherwise – was surveilling Chandeleur Sound as U-507 crept closer and closer to the mainland.

On orders from Kriegsmarine U-boat Admiral head Karl Dönitz, U-507 and her insidious partner, U-506, had spent the previous two weeks pummeling merchant ships in the Gulf of Mexico. Hitler and Dönitz were hellbent on using submarine attacks to undercut American morale and undermine the Allies’ capacity to wage war.

In her 12 days in the Gulf, U-507 alone had sunk eight freighters, four of them oil tankers, inflicting hundreds of casualties. Beachcombers from Brownsville to Biloxi watched in horror as human remains washed ashore amid boat wreckage and oil slicks. Just as they had up and down the East Coast, Nazi submarines were spreading panic in the Gulf, triggering shrill headlines (“WAKE UP, GALVESTON!”) and sparking fears of Fifth Column saboteurs signaling enemy ships from coastal hideaways.

Now, a few minutes after three o’clock on Tuesday afternoon, May 12, 1942, the 245-foot leviathan – nearly three-fourths the length of a football field – was again waiting to strike, this time submerged in shallow water. Just eight meters separated her hull from Delta muck. The Gulf churn was unusually calm, unbothered by a light breeze. The skies were clear; so was the view from U-507’s periscope.

Moments before, her skipper, Korvettenkapitäin Harro Schacht, had glimpsed through his ‘scope a pair of U.S. Navy patrol craft hovering close to shore. But Schacht didn’t budge: he knew from intelligence reports – quite possibly fashioned by Nazi Germany’s one-time consul-general in New Orleans, Baron Edgar von Spiegel, who had taken copious notes while on prewar “fishing trips” – that fat pickings were likely to appear at the mouth’s Southwestern Pass.

Soon enough, Schacht spotted the S.S. Virginia, an unescorted and unarmed 10,000-ton tanker that in Baytown, Texas, had been loaded with 180,000 barrels of gasoline. Before heading upriver to Baton Rouge, the Virginia had anchored abreast a buoy, waiting on a pilot to be ferried from the mainland. She could not have been more vulnerable, especially when the two Navy vessels wandered away.

Schacht had been U-507’s captain for less than a year, yet was already wreaking so much havoc that he would soon be awarded the Fatherland’s ultimate commendation, the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. Schacht wasn’t wearing any medals as he took dead aim at the port side of the tanker owned by National Bulk Carrier Ltd. of New York, a shipping concern that was then one of the world’s largest multinational companies.

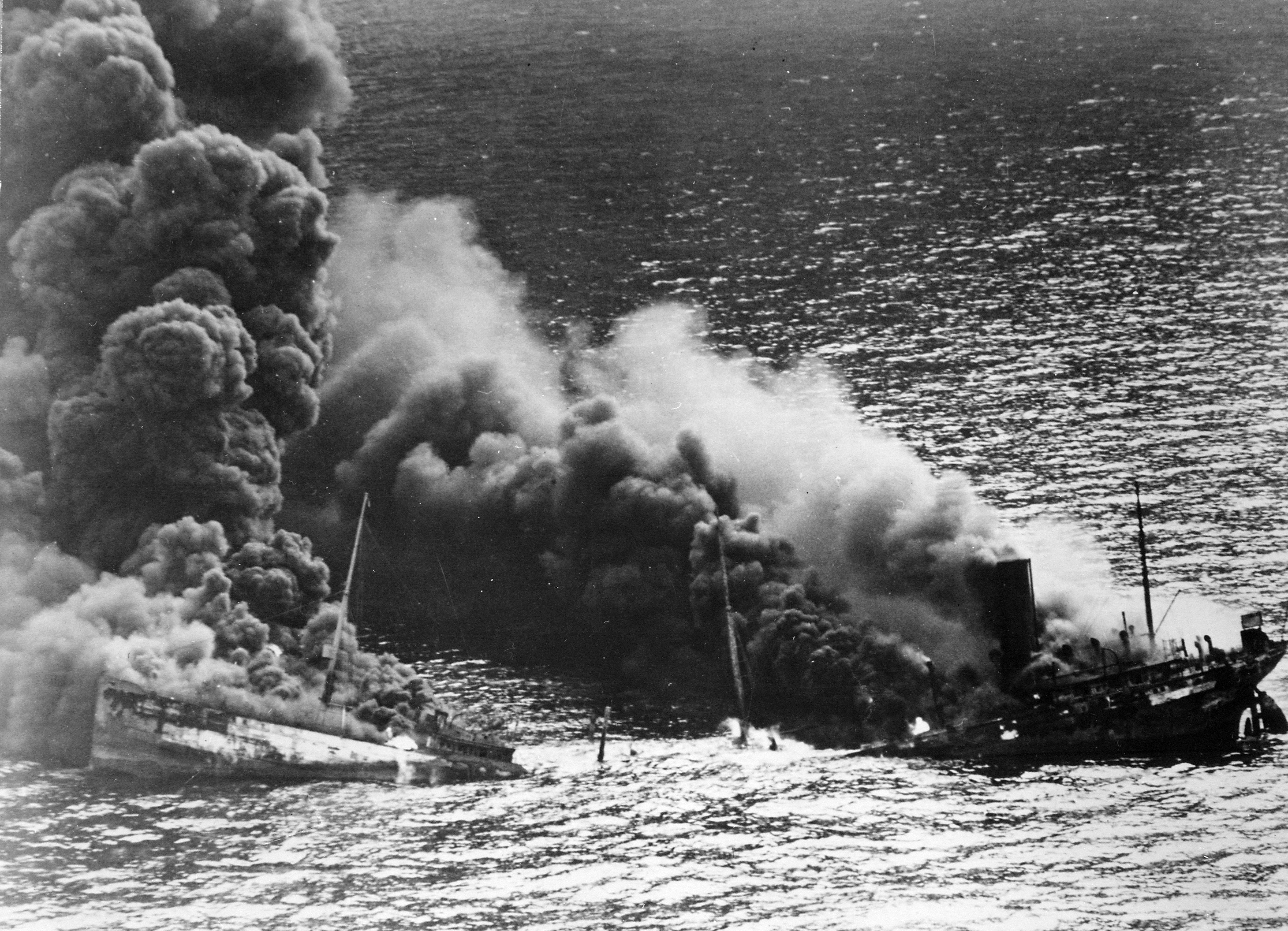

No one on aboard saw the torpedo’s wake: Schacht’s first salvo hit the unsuspecting Virginia amidships. Virginia’s captain tried to get underway to save his crew, but he was up against utter mayhem; there was no chance to hoist anchor or lower lifeboats.

Seconds later Schacht’s second and third torpedoes thudded into the Virginia port side with such ferocity that she was severed; flames enveloped both sides. Twenty-seven of her 41 crew members died hellish deaths. Most of the 14 survivors were severely burned; two were so badly hurt they couldn’t move without help. Their lives were saved by heroic shipmates.

Those who could threw themselves into the water on the windward side, thrashing away from the ship as fireballs ripped across the Sound. Finally, after a half an hour, a Navy PT boat rescued them.

By then, their ship had disappeared. The remnants of the Virginia plummeted to a depth of 200-plus meters on the precipice of the continental shelf. Three-quarters of a century later, they’re still there.

Despite Navy and Coast Guard boats having gone on full alert, Schacht slipped away to renew a reign of terror in the Gulf that, by mid-June, would include attacks by seven of Dönitz’s prized U-boats. The Nazis’ malignant presence in the Gulf was testament to just how many defenseless tankers were plying its waters.

Unlike certain conquests, Schacht chose not to break the surface to admire his handiwork and wisecrack with his victims. Eight days earlier, the U-boat skipper had handed out 40 packs of cigarettes and a cache of crackers, French cookies, ten gallons of lime pulp, and drinking water to the surviving crew members of the Norlindo, a steam freighter he had just torpedoed 80 miles northwest of Dry Tortuga Island. After killing five of their shipmates, Schacht bantered from the U-507’s bridge with the 23 survivors in impeccable English, showing off an impressive flair for American slang, so impressive, in fact, that it stirred rumors that the notorious Baron von Spiegel himself was skippering the sub. He assured the men frantically trying to stay afloat that he felt bad for putting them there. The war was all Churchill and Roosevelt’s fault, Schacht snarled before steaming away.

His partner, U-506’s Erich Würdemann, a Kapitänleutnant, had spent May 12 stalking the Gulf south of the Sound. Toward nightfall, U-506 slid northward to examine the damage exacted by her sister ship.

Würdemann later reported that the inferno fueled by the Virginia’s ruptured gasoline could still, hours after the attack, be seen for 30 nautical miles. Revelers on New Orleans’ Bourbon Street could smell the stench that night and into the next day.

The river that Abraham Lincoln once venerated as the “Father” of all American waters was, 80 years removed from the siege at Vicksburg, again the site of horrific bloodshed.

Schacht and Würdemann, their exploits already legendary, returned to the Nazi U-boat pen at Lorient, France, to heroes’ welcomes and eventual Iron Crosses. For Hitler’s cutthroat submarine skippers, the war would never again go so smoothly.

“The Americans, apparently, had not anticipated the appearance of U-boats in such far distant parts of the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico,” Dönitz bragged in his memoirs. “Once again, we had struck them in a soft spot.”

A Jittery Country Under Siege

In the harrowing months following Pearl Harbor, Nazi U-boats and Japanese submarines found plenty of soft spots in America’s coastal defenses. Given the woeful state of its armed services, the entire country was susceptible to attack, especially along its shorelines. “The Navy was spread far too thin to keep the Nazi sharks at bay – and the tankerman who sailed past Cape Hatteras (NC) alive counted himself lucky,” wrote civil aviation historian Robert E. Neprud after the war.

Between January and August 1942, German U-boats destroyed nearly a quarter of the prewar U.S. oil tanker fleet. In the first two months of ‘42 alone, Dönitz’s grey wolves wrecked 22 tankers, hobbling not only America’s readiness, but Britain’s and Russia’s as well, since much of that oil and gasoline was headed toward Liverpool, Vladivostok, and other key Allied ports. Freighters carrying tanks, guns, and ammunition to the Brits, Russians, and Chinese were also sent to the bottom with alarming frequency.

So many U.S. ships shared the Virginia’s fate during the month of May that the War Department squelched the actual figure (allegedly 33 in the Gulf-Caribbean and 19 in the Atlantic), for fear it would cause public panic. The situation got so dire that for several weeks coastal vessels were ordered to remain anchored, rather than risk the wrath of U-boats. Overall, Dönitz’s Unterseeboot-Flotte sank some 300 U.S. ships in the first two-thirds of ‘42, killing 5,000 seamen and passengers, more than double the fatalities suffered at Pearl Harbor.

U-boat commanders called early- to mid-’42 their “Second Happy Time.” The first happy stretch had occurred early in the war amid the original Torpedo Junction, the waters around the British Isles, before England could assemble the planes, ships, and manpower to counter the sub menace.

Sometimes, U-boat commanders were so brazen that they attacked while on the surface, blasting away with a pair of withering 88-millimeter guns that could hurl 20-pound shells at ships’ waterlines. They also learned, as Horro Schacht had demonstrated in the shoals off Chandeleur Sound, that the most effective way to spring an attack while submerged was from the inshore side.

Galvestonians weren’t the only Americans awakened by the wanton brutality of Hitler’s submariners: the British freighter Coimbra was torpedoed so close to the Long Island shore that Quogue residents called their local fire department, convinced that the explosion had happened on land. It wasn’t just the Mississippi that U-boats had infiltrated; ships were obliterated in the mouths of the Connecticut and St. Lawrence Rivers, too. Locals swore that Nazi subs also snuck into Florida’s Banana River near Cocoa Beach and Maine’s Kennebec River not far from Brunswick.

On at least two occasions, folks strolling Atlantic City’s boardwalk were subjected to the macabre spectacle of merchant ships being hounded – and sunk – by U-boats in broad daylight. Andy Pew, the scion of the Sun Oil Co. fortune, always claimed that he witnessed one his family’s tankers get torched from the window of his south Jersey hotel. Motorboat owners in Provincetown at the tip of Cape Cod found themselves racing out to sea to rescue sailors and soldiers after a troopship had been torpedoed.

On the Pacific coast, the situation was less dire, but still disquieting. In late February, I-17, a Japanese submarine, surfaced at sunset in Santa Barbara Channel and shelled an oil refinery in Ellwood. The attack happened in the middle of President Roosevelt’s celebrated “map speech,” just as FDR intoned on the radio that, “The broad oceans which have been heralded in the past as our protection from attack have become endless battlefields in which we are constantly being challenged by our enemies.”

Almost miraculously, no one was hurt in the Ellwood barrage; the damage to the petroleum facility and nearby villages turned out to be minimal. But I-17 and her sister subs attacked multiple ships in the waters off California and the Pacific Northwest and shelled forts along the Oregon and British Columbia coasts. Months later, an immense Japanese sub-carrier (more than 100 feet longer than U-507!) launched a seaplane that twice tried to ignite forest fires in Oregon by dropping incendiary bombs.

Again, the onshore damage was negligible. But the country’s vulnerability to seaborne assault put the lie to Charles Lindbergh and the America First movement that the Atlantic and the Pacific somehow insulated the U.S. from attack. The Allies’ “entire war effort” was now threatened by enemy submarines, Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, who became President Roosevelt’s chief military advisor, said in early ‘42.

The lethal battering on all three coasts forced U.S. military planners – Marshall among them – to conclude that desperate times called for desperate measures. If the U.S. military wasn’t yet capable of providing more than token protection of its coastlines, then the government would have little choice but to ask civilian pilots, mechanics, boatmen, and others to step into the void.

The Spirit of Lexington and Concord

What ensued was the most stirring grassroots response to an armed threat since Lexington and Concord. Instead of “one if by land and two if by sea,” the civilian mobilization in the early months of WW II was directed almost exclusively at a seaborne threat – combating it through the air as well as on the water.

Stephen E. Ambrose, the great WW II historian, liked to refer to the American servicemen and women who were willing to sacrifice everything to liberate Europe and vanquish Imperial Japan as “citizen-soldiers.” The ordinary civilians who answered their country’s call of duty in the dark days of WWII – including tens of thousands of females who served as pilots, sailors, observers, mechanics, and clerks – could be described as “citizen-volunteers.”

Lieutenant Stuart M. Speiser, an assistant intelligence officer at a civilian aviation base in Louisiana, said after the war that the citizen-volunteer push involved “young and old, stout and thin, rich and poor, who by both spirit and deed have given their nation a soul-stirring example of what Americans can do in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles.”

The citizen-volunteers of 1942-1943 came from all walks of life: bus and bakery truck drivers, doctors, nurses, teachers, plumbers, lawyers, farmers, homemakers, shoe clerks, shopkeepers, laborers, writers, actors, and more than a few millionaires – even a Member of Congress! Prominent families from New York City’s Social Register – people named Astor and Vanderbilt – lent pricey yachts and ship-to-shore radios to the cause.

At the other end of the spectrum, some biplane barnstormers from the old carnival days showed up for duty. This time they wouldn’t be wing-walking; they’d be submarine-stalking.

Instead of the muskets, musket balls, and gunpowder of yore, they brought with them their own planes, boats, radios, repair parts, tools, firearms, and fuel. Many of them were forced to quit their jobs or take extended leaves of absence from work and family.

Some of the aviation volunteers did it for a modest per diem that ranged from $5 to $8 – if they got paid at all. Sometimes the government checks were late; sometimes they never arrived. Most of the seafaring volunteers used their own boats to hunt subs and escort freighters without compensation of any kind, including reimbursement for fuel.

Records are incomplete, but through the course of the war, at least 68 American citizen-volunteers gave their lives in service to their country. Many more were injured in plane or boat accidents or mishaps around the airstrip, hangar, or pier.

Their sacrifice was buttressed by a corporate generosity unprecedented in American history. Leaders from the energy sector, especially, stepped up to lend resources to the cause. As U-507 and her sister boats preyed the Gulf, torpedoing tankers with impunity, area oil companies led by Cities Service, Inc., the precursor company to CITGO, passed the hat, raising funds through the Petroleum Industry War Council to help underwrite a civilian antisubmarine effort.

Soon enough, those private monies weren’t needed. But in the early days of the war, they were indispensable.

Before war’s end, a quarter-million people would be actively engaged in America’s concerted civilian mobilization effort, among them future Tuskegee Airmen; two pioneering aviatrixes, one African-American, one Caucasian; a popular comic strip artist; a renowned concert pianist; accomplished Hollywood figures of both genders; a Munchkin from the Wizard of Oz; various Wall Street financiers and corporate poohbahs; the head of a major brewery; and – never to be forgotten – the country’s most celebrated novelist and its most revered “tough-guy” actor.

Dozens of other notable Americans from Hollywood, Broadway, and the corporate world would bring their own planes and boats to the cause. They hawked hostile submarines, rescued downed pilots and U-boat attack survivors, surveilled thousands of miles of coastline, towed targets to give military personnel a chance to practice their gunnery skills, protected the country’s borders, spotted forest fires, ferried important people and equipment, provided emergency blood transport services to the Red Cross, and escorted critical freighters from port to port.

On occasion, they tangled with the enemy and held their own.

The Year That Tried Men’s Souls

It wasn’t just the Kriegsmarine that bedeviled the Allies in early-to-mid ‘42. The Wehrmacht had blitzkrieged some 800 miles into Russia and was poised to capture Stalingrad. Indeed, Hitler’s army had not yet retreated from the territory it had seized in Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, the Low Countries, France, or North Africa. Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe was still in firm control of the skies, meeting little resistance as, almost at will, it bombed and strafed Allied cities and strongholds.

Meanwhile, Dönitz’ Paukenschlag, “Operation Drumbeat,” had led to open season against U.S. shipping for the bulk of ‘42. The Imperial Japanese Navy, too, had an ambitious – if ultimately unsustainable – submarine attack plan against the U.S., known as “Operation Storm.” American leaders fretted that little could be done if the Japanese chose to harass the U.S. Pacific coast or attack the Panama Canal.

U.S. strategists were charged with waging a two-theater war whose front lines were tens of thousands of miles apart; yet in 1942, they could not guarantee safe passage of Allied vessels within hundreds of yards of the U.S. shore.

Intelligence leaders and the public alike also worried that the U.S. was rife with spies and saboteurs. In 1941 – before the U.S. entered the war – the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) uncovered a massive German espionage ring in New York City. Thirty-three Nazi agents were caught red-handed and, after a sensational trial, sent to jail.

Seven months after Pearl Harbor, U-boats operating at the command of German espionage chief Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, the head of Abwehr, deposited four trained saboteurs at the southeastern tip of Long Island and four more in northeastern Florida. They were armed with wads of cash, explosives know-how, and marching orders to blow up such targets as hydroelectric plants on the Niagara River, aluminum factories in New York State, Tennessee, and Illinois, locks on the Ohio River outside Louisville, and bridges and rail depots in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York State.

The fact that one of Canaris’ operatives fingered the others before they could carry out their skullduggery hardly assuaged fears. Surely, Americans reckoned, Hitler, Tojo, and Mussolini would dispatch other bands of saboteurs. And existing spy rings were surely plotting to sew chaos around the continent.

No Army base, no Navy port or repair dock – maybe no civilian airport or rail station, anywhere – was safe. Some 4,000 miles away from the nearest infantry skirmish between Allied and Axis forces, Americans had every reason to feel threatened.

Those legitimate fears fed a paranoia that U-boat crews were treating coastal communities like personal playgrounds. Stories abounded that enemy submariners had been spirited ashore via rubber boats to take in a picture show or spend the evening swilling beer at a local pub.

“These tales were later discredited,” Neprud wrote, “but the fact that they were accepted by many persons as the truth is evidence of the jittery state of the nation.” U-boats may not have dropped anchor in coves along the U.S. coastline, but in mid-ocean or mid-Gulf, while on the surface to recharge their batteries, their crews liked to sunbathe or go for an occasional swim.

The naiveté and pocketbook interests of eastern seaboard merchants also contributed to the mythic prowess of the U-boats. It took until April 18th of ‘42 before the Eastern Sea Frontier ordered coastal communities to begin imposing nighttime blackouts, which didn’t come close in severity to matching the mandatory blackout restrictions that Britain had put in place from ‘39 onward. Scarcely believing their eyes, U-boat captains took advantage of America’s bright city lights, turning silhouetted tankers into funeral pyres, sometimes within sight of horrified city dwellers.

“One of the most reprehensible failures on our part,” wrote the great naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison, “was the neglect of local communities to dim their waterfront lights, or of military authorities to require them to do so, until three months after the submarine offensive had started.”

Nineteen forty-two, writer Winston Groom avers, was “the year that tried men’s souls.”

Decrepit Planes and Boats

As oils slicks continued to soil the seascape from Nantucket to Padre Island, Winston Churchill characterized the U-boat menace as a “measureless peril” to the Allied cause. Churchill later admitted that the hemorrhaging in the Atlantic and the Gulf was the only time in the entire war – including the Nazi bombing Blitz of England – that he feared for its outcome.

Churchill wasn’t alone. It quickly became apparent to such top U.S. planners as Eastern Sea Frontier Commander Admiral Adolphus “Dolly” Andrews and Assistant Secretary of War for Air Robert A. Lovett, that America’s defenses were porous and would likely stay that way through the first year of war – perhaps longer.

At the outset, all Andrews had at his disposal to patrol more than 1,200 miles of Atlantic coastline were 103 decrepit planes and fewer than two dozen boats, most of them wholly inadequate. Readiness in Captain Russell S. Crenshaw’s Gulf Sea Frontier, which came into being in early February, was even more slapdash.

“There were two officers and four boats to protect the Florida Straits, most of the Bahamas, all of the Gulf of Mexico, the Yucatán Channel, and most of Cuba,” writes contemporary historian Melanie Wiggins. In the event of an “emergency,” the Gulf Sea Frontier was told in the winter of ‘42, a few planes and boats from the Navy/Coast Guard base at Key West might be available to the Gulf Sea Frontier.

All of which caused war strategists to reassess civilian aviation capabilities. The civil air numbers at war’s inception at least gave planners something to work with: in early ‘42, there were 128,000 certified pilots in the U.S., 14,000 airplane mechanics, and 25,000 light aircraft. More than a few American pilots and mechanics crossed the border between ‘39 and ‘41 to volunteer for the Royal Canadian Air Force or eventually join an Eagle (all-American) squadron with the British Royal Air Force.

It would take the U.S. many months to build the reconnaissance aircraft, the destroyers, the patrol boats, et al. – not to mention conduct the hands-on military training demanded by early war exigencies. The only option for the time being, the likes of Andrews and Lovett concluded, was to empower certain civilian groups that had sprung up around the country. Even before Pearl Harbor, these ordinary Americans had been hectoring officials for a chance to prove their worth.

Lovett, who’d served as a naval ensign in the First World War and was smitten by the British Naval Air Service, became an outspoken advocate of U.S. civilian aviation as a stop-gap measure. He knew from his consultations with the Brits that the only way to contain U-boats was to deploy airplane surveillance and destroyer-led convoys – neither of which the U.S. military in 1942 could provide. Until they could, civilians would have to fill the void.

Stepping into the breech in early to mid-1942 were tens of thousands of men and women who signed up for the Civil Air Patrol (CAP), soon nicknamed “The Flying Minutemen”; the Corsair Navy, soon dubbed “The Hooligan Navy”; and the Navy-Coast Guard’s volunteer coastal patrol, soon labelled “The Bucket Brigade.” Putting aside personal and family needs, these men and women traveled hundreds and, in some cases, thousands of miles to live in crude conditions, eat forgettable food, spend a bunch of money from their own pocketbooks, put their careers on hold, and put their lives on the line.

Legacy Overlooked by Historians

Sadly, the WW II valor of these ordinary Americans has receded from memory. Three quarters of a century removed from the undersea terror at our doorstep, their contributions to the Good War too often get overlooked.

Contemporary WW II historians tend to give their effort short-shrift. The Flying Minutemen weren’t mentioned in Melanie Wiggins’ Torpedoes in the Gulf, which is astounding given the risks undertaken by the gritty civilian pilots who operated out of Grand Isle, Louisiana, Brownsville, Texas, and other CAP bases in the Gulf.

Volunteer aviators and boatmen also got scant attention in Homer H. Hickam, Jr.’s Torpedo Junction, which details the bloody U-boat campaign off Cape Hatteras, where German captains would “hide” along rugged stretches of the continental shelf, picking off freighters.

It’s true that U-boats didn’t leave the Hatteras region (and with it, the rest of the U.S. coastline) until ordered by Dönitz in the fall of ‘42. But it’s also true that CAP planes from Manteo, Beaufort, and other bases, plus Hooligan Navy and Bucket Brigade boats, helped dissuade enemy subs from launching attacks off Carolina’s Outer Banks.

Almost as sadly, the real story of America’s WW II citizen-volunteers was embellished by excitable writers during and after the war, distorting their actual mission and creating a false sense of bravado.

No, these extraordinary men and women were not attack dogs with a string of enemy “kills” to their credit. Despite popular mythology, they never sank a U-boat or captured German sailors or stopped enemy saboteurs in mid-treachery.

Instead, they could best be described as combination “rescue dogs” and “scarecrows” – the emergency force that America needed in the dicey days of WW II. Ultimately, they served as “guardian angels,” protecting ships from attack, airstrips and infrastructure from sabotage, and borders from being violated. Their courage, like the peril they sought to diminish, was measureless.

Some 5000 British citizens and 850 private boats participated in the remarkable cross-Channel rescue operation at Dunkirk. In the span of eight days in the spring of 1940, those citizen-volunteers saved the British Expeditionary Force from annihilation. Dunkirk is justly celebrated today by historians and Hollywood alike. It has become an iconic and endearing part of WW II lore, a sublime expression of solidarity.

Yet America’s citizen-volunteer effort involved infinitely more civilians, planes, and boats. And it lasted not for a week, but for the better part of 18 months. It’s a shame it hasn’t gotten more attention.

[Part II of this series will explore the amazing courage and sacrifice of members of the Civil Air Patrol along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts]