The American War for Independence was part of an international trend -- a new focus on the individual that inspired people to new insights, new proclamations, and new assertions of rights.

-

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books

Volume64Issue5

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist Revolution Song: A Story of American Freedom, by Russell Shorto.

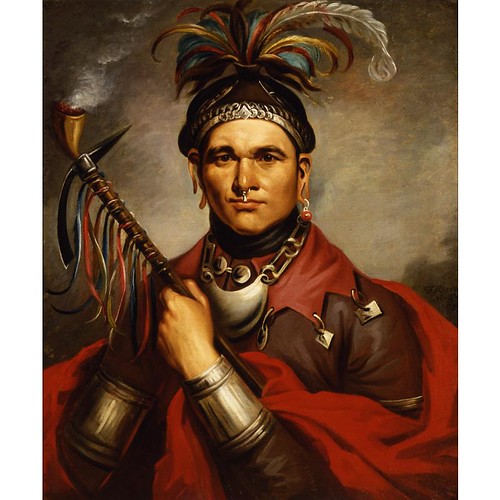

He was a wise man, a family man, with a kind face and soulful eyes, and he was about to kill. The people he was going to kill called themselves Americans. That word had nothing to do with him, though it would be foisted onto his identity and that of his people. He was a Seneca, a leader of the Haudenosaunee, the confederacy that the whites called the Iroquois. His name was Kayethwahkeh. Its meaning in the Seneca language had within it the idea of planting. That, coupled with the fact that corn was the most visible crop around Seneca villages, led Americans to call him Cornplanter.

Cornplanter was a young man, in the prime of life, tall, broad-shouldered, built for action. On this night, July 27, 1779, under cover of darkness, he led 120 men, armed with muskets and tomahawks, along a stream that fed into the Susquehanna River in central Pennsylvania. They surrounded a rough stockade. Inside were 21 American militiamen and about 50 women and children. At dawn one of the men in the makeshift fort appeared at the gate; the gunshot hit him with a force that knocked him back inside. Rather than accept the warning, the militiamen started shooting back. They were outnumbered and inexperienced; they had no idea what was to come. The puff and crack of musket fire filled the morning air.

Cornplanter had not wanted to be in this position: he hadn't wanted to kill Americans. But there were others who had a say, and as a political leader he understood compromise and majority rule. Earlier, at the British fort in Oswego, on the shore of Lake Ontario in Seneca country, representatives of the king of England — alien creatures in their red-and-white dress, smelling of beef and vinegar — had organized a formal council with leaders of the Iroquois confederacy, including Cornplanter. They brought out a wampum belt whose rows of colored beads signified the age-old alliance between Great Britain and the Iroquois nation. They talked about the war that was going on between their country and the American colonists, told of the majesty and might of Britain and her king, and of the inferiority of the Americans. They wanted the Iroquois to join the fight on their side. They gave presents: brass kettles, muskets with their beautifully long and cold barrels, gunpowder, sharp knives of the kind the Iroquois preferred for scalping.

The Iroquois leaders then conferred among themselves. Over the years their people had had frank business dealings and even friendships with American settlers, but settlers had also burned Iroquois villages, murdered their families and taken over their lands. The Mohawk Thayendancgea, a worldly and domineering war chief who also went by the English name Joseph Brant, argued forcefully that if the Americans defeated the British the land-grabs would continue, therefore the Iroquois should fight alongside the British. Besides, the British were stronger; it would be better to back the likely winner.

Then Cornplanter rose to speak. There must have been some fidgeting, for he was an unusual man and the others knew it. While he was a trained fighter — something of a killing machine, in fact — he had the temperament of a philosopher. He was a ponderer, a quiet, slow thinker given to aphoristic pronouncements, whose words, belying his relative youth, often reflected the pain and sadness of life. He had not been swayed by the arguments or the gifts of the British.

Cornplanter called the war between the British and the Americans a "family quarrel." He suggested that it was wiser to stand back and let the white tribes fight it out. "War is war, death is death, a fight is a hard business," he said.

Joseph Brant had evidently been expecting this sort of thing from Cornplanter. He leaped to his feet, commanded Cornplanter to "stop speaking" and referred to him as "nephew" — a term of subordination — even though they were equals. He branded Cornplanter a "coward," and urged others to vote to fight alongside the British.

The vote went against Cornplanter. The Iroquois became part of the American Revolutionary War, launching a murderous string of assaults on American villages and forts. Cornplanter, the philosopher, led the way, leaving horror in his wake.

Three thousand miles away, across the vast buffer of the Atlantic Ocean, sat the man who had forced Cornplanter's hand. As Secretary of State for the American Department, Lord George Germain was England's de facto secretary of war, the man whose job it was to devise a strategy for quelling the rebellion.

Where Cornplanter's world comprised forest trails and longhouse villages, Germain's was one of London's gentlemen's clubs and country estates, of diamond broaches for the ladies and bumpers of claret for the men, of such novel distractions as Samuel Johnson's dictionary and symphonies of Herr Mozart. He was a tall man, "rather womanly" in the way his body expanded in the middle, as an acquaintance put it, yet with the bearing of the war-hardened soldier he had once been. He was a convivial socializer, but so charged with aggression that even friends tended to hold him at arm's length.

Germain had thought it would be quick, this business of corralling the Americans. The original plan he put in motion was, as he said, "decisive, direct, and firm." British armies would take command of the Hudson River and drive a wedge between New England and the rest of the colonies. Split in two, America would end its rebellion. But in December 1777 news reached London that General John Burgoyne had been beaten so decisively that he had had to surrender his entire 6000-man army to American forces on the banks of the Hudson.

The outcry in Parliament was immediate, and blame was showered on George Germain. The word his enemies unfurled was precisely the one the Mohawk chief had flung at Cornplanter: coward. It was a strange term to use for a plan that had involved full and direct military engagement. But Germain's conduct in running the war against the American revolutionaries had a deeply personal bent to it. He was, in a real sense, using the vast, world-historic conflict to exorcise a personal demon.

Stung by his political enemies' attacks, Germain devised a new strategy for defeating the Americans. From now on the English offensive would be more complex, carried out on a grander scale and with fewer scruples. Among other things, he issued precise instructions for bringing the Iroquois into the conflict on the British side.

If George Germain had forced Cornplanter's hand, then the attacks that Cornplanter and his fellow Iroquois unleashed - a reign of terror across Pennsylvania and New York that left dismembered bodies and traumatized survivors - likewise forced the hand of the colonial army leader. From his military camp in Middlebrook, New Jersey, General George Washington made the hard decision to pull 4,000 men - nearly a quarter of his entire army - out of the fight against the British and direct this force at the Iroquois.

At this point, three years into the war, Washington was beset with difficulties. The British had taken two forts on the Hudson River, and it seemed they might yet achieve the goal of splitting the colonies in half. The American soldiers were practically barefoot: the army was desperately in need of shoes. And now Washington had to divide his army to fight Indians. The news from his home, Mount Vernon, meanwhile, was also bleak: crops hadn't been planted, and there was no money for upkeep.

Washington was forty-seven years old, a Virginia planter who, with his ascendance to lead the American army, had achieved what he had craved all his life: attention, honor, status. He was fastidious in dress and took great care in public appearances — making sure, for instance, that he always showed himself to his men, even when all was mud and slop, wearing the most resplendent uniform and atop the finest horse. Like George Germain, he was deeply ambitious, but where Germain's drive seemed to blare from his being, Washington kept his hunger for success hidden behind a frosty reserve.

Also like Germain, Washington had personal motivations as he led his army. Throughout his teens and twenties he had strived for a place in Britain's military. Time after time he had been rejected by the British system as a mere colonial, and he became progressively more bitter. The Revolution slowly brought about a transformation in him. He had grown up with a fawning admiration for all things British, yet he was now the leader of the greatest-ever rebellion against Britain. He was an Anglo-American who, increasingly, saw himself simply as an American.

As the war ground on, the Seneca warrior Cornplanter, the British aristocrat George Germain (whose name at birth was George Sackville), and the American general George Washington were propelled by a common drive. Each was a leader of his people. The concept of political freedom, which swept through the eighteenth century with unprecedented urgency, thrust them together in conflict.

But political freedom and representative government, the ideas that we most associate with the American Revolution, earthshaking though they were, were part of an even larger force that was in the air at the time. This broader change in how humans saw themselves had been building for more than a century by the time Washington, Germain and Gornplanter were active. I was first struck by it while researching my 2004 book The Island at the Center of the World, about the Dutch founding of New York in the 1600s. In that century, people began to distrust old ways of knowing and developed a new appreciation for the human mind and what it could discover. In the mid-1600s, René Descartes, the so-called father of modern philosophy, proposed the radical notion that knowledge ought not to be grounded in "received wisdom" — that whatever the church or the king said was true — but on the human mind and its "good sense." Every single person had within himself or herself a tool called reason, which connected to the world and the universe in a mysterious and profound way.

From this came an elevation of the individual, a newfound fascination with the individual — or, better said, a new meaning of "individual." Before, your definition of yourself was inextricably bound up with your relationships and networks: your family, guild, village, manor, parish. "You" were a thread in a web. Then, suddenly, you were ... you. And you were uniquely special and important.

As the eighteenth century progressed, the focus on the individual led people to new insights, new proclamations and assertions of rights. Across Europe, a particular word was suddenly bandied about in every conceivable context. Vrgheid. Liberdade. Liberte. Svoboda. Saoirse. Freedom. Kings, armies and churches, whether you sided with them or not, all exerted power over individuals; all, in their very existence, constrained these newly assertive individuals. In country after country, people began agitating for freedom of one kind or another. The furor built through the decades until the leaders in America had the brilliant idea to package this force. They gave it a sharp political frame and turned it against the English, who had themselves been at the forefront of the freedom movement. The Americans declared that it was "self-evident" that all are created equal, and that all are entitled to "liberty."

They were like us, vibrantly aware of themselves as individuals, alive to promise and possibility in a way that previous generations had not been. But the new valuing of the individual went only so far. "Liberty" had strict limits in the early American republic.

Yet people who were left out of the "all men are created equal" struggle in the period of America's founding pushed forward in their own ways. The three other protagonists of my book, whose lives weave through and around those of Washington, Germain and Cornplanter, didn't lead armies, but they personified "revolution" as fully as did the man who becalm the first president.

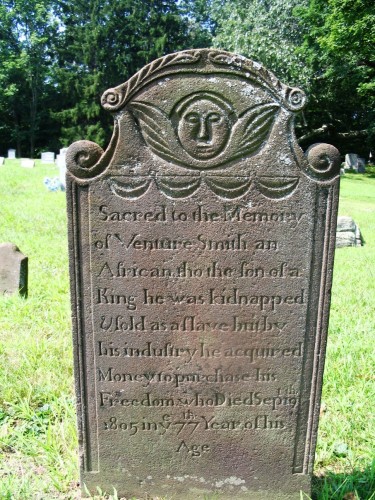

Venture Smith, who was born in Africa (his original name was Broteer Furro) and brought to America as a slave, embodied the complications of the struggle for freedom better than any patriot soldier. While America's leaders packaged the power of individual freedom and wove it into grand, idealistic language, it did not inspire them to end slavery. That failure led to what has probably been the greatest source of strife in American society. For many, it continues to make the project of American history feel hollow. But Venture Smith cut his own path: buying himself and his family out of slavery, acquiring land and, against all odds, fostering a community of free blacks.

The emancipation of slaves at least was a topic of debate in the eighteenth century. Women's freedom — the idea of women being independent actors, able to make their own way in life — was mostly unimagined. Margaret Moncrieffe was the daughter of a military officer who chose to fight on the British side, and the whole trajectory of her life was shaped by his decision. A young woman couldn't express herself with anything like the independence that men could assert, but she clutched at one hopeful change that women were advancing just as she came of age: the rejection of forced marriage. Defying both her father and her abusive husband, however, came with a heavy price. Most of her life unfolded in London and Paris as she cycled back and forth between high society and the depths of poverty. From today's vantage point we can see that she was trying to make it on her own. That was virtually impossible for a woman of the time, but she had tools at her disposal, including her femininity and a remarkably modern flair for self-promotion, which she employed with great skill.

We are used to seeing the American Revolution through the eyes of the elites of the period: men in powdered wigs who scratched out words of wisdom on rag paper. Like many of the founding fathers, Abraham Yates Jr., of Albany, New York, made freedom his life's work, but he stayed resolutely at street level. He was the son of a blacksmith who was relegated to the humblest of careers, that of shoemaker. He seems to have been born with a keen sense of injustice, however, a feeling that the "better classes" were trampling the commoners. So he taught himself the law and rose through a succession of local political offices. He was among the first Americans to grow impatient with British rule, one of the first to bring the writings of John Locke to bear on the American situation, and among the first to join the patriot cause. But his voluminous writings have little of the loftiness of the founding fathers' documents. Instead, they are pragmatic and suspicious, always reflecting his tradesman's perspective and distrust of elites, British and American alike.

In one sense, these three people of the 18th century stand for others, people whose freedom was limited. But to define them in terms of issues - slavery, women's liberty, the struggle of commoners versus elites - feels too cramped. They were not representatives of groups. They were gorgeously themselves. As I researched their lives, they seemed to reject categorization; like each of us, they demanded uniqueness.

My objective is to offer not just an account of the era in which the American nation was founded, but a sense of what it felt like. Philosophers say that human subjectivity is the one wall science can never break down: we will never know scientifically what it is like to experience life from someone else's perspective. But art can do this, and I believe that history has an element of art in it.