Three times John Glover’s Marblehead fishermen saved Washington’s army; in a final battle, the “amphibious regiment” rowed him to victory across the Delaware

-

February 1960

Volume11Issue2

Some years after the Revolutionary War, Henry Knox, one-time major general and chief of artillery in the Continental Army, rose before the Massachusetts legislature to speak on a bill in behalf of his former comrades in arms, the Marblehead fishermen. Standing there, his hulking 280-pound frame commanding every eye, Knox recalled the cold Christmas night in 1776 when these brave men had ferried Washington’s army across an ice-jammed river to launch the attack against Trenton.

In a booming voice that filled the hall, Knox recounted that memorable episode. “I wish the members of this body … had stood on the banks of the Delaware … in that bitter night … and seen the men of Marblehead, and Marblehead alone, stand forward to lead the army along the perilous path to … Trenton. There, Sir, went the fishermen of Marblehead, alike at home upon land or water … ardent, patriotic, and unflinching whenever they unfurled the Hag of the country.”

Such was the caliber of John Glover’s regiment, one of the most unusual units in the whole Continental Army. It was composed almost entirely of seafaring men from Marblehead, soldier-sailors who could march onto a battlefield or tread a ship’s deck with equal ease. Able to handle oars as well as muskets, they were ordered to man small ships and boats for the Army so often that they have gone down in history as the “amphibious regiment.”

Everything about the regiment smacked of the sea. Many of the men marched oft to war in the same blue jackets, white caps, and tarred trousers they wore off the Grand Banks. Even the famous discipline of the unit was the result of their occupational training. Unquestioning obedience to the captain was the rule of the sea; the officers of Glover’s regiment made it the ride of the land as well. One Pennsylvania officer who ordinarily took a dim view of New England troops was forced to admit that this outfit was different: “There was an appearance of discipline in this corps … it … gave a confidence that myriads of its meek and lowly brethren were incompetent to inspire.”

Most Marbleheaders were foes of England because of the Fisheries Act, passed in the spring of 1775, which threatened to deprive them of their livelihood by barring them from North Atlantic fishing grounds. Out of this hatred a provisional regiment of minutemen was born in Marblehead three months before the rattle of musket fire was heard at Lexington and Concord. Indeed, Marbleheaders came close to filling the niche in history held by Lexington minutemen. On February 26, 1775, a British regiment under Colonel Thomas Leslie landed off Marblehead Neck, headed toward Salem and a hidden store of patriot arms and ammunition. It was a mission exactly like the Concord mid that precipitated war two mouths later.

The entire Marblehead regiment turned out, and although they were too late to halt the British, they took up positions along the road to give Leslie’s troops a hot reception upon their return. But Salem patriots removed the military supplies out of reach of the British, and after a clergyman intervened to prevent bloodshed, Leslie agreed not to press his demands that they be surrendered, instead of firing upon the redcoats as they returned empty-handed to their transports, the Marbleheaders formed an escort behind Leslie’s men and marched in mocking cadence to the British music.

Like most units of Massachusetts minutemen, the regiment underwent a series of reorganizations after war broke out, but two factors made for continuity. Most of the men still hailed from Marblehead, and from the spring of 1775 through the winter of 1776, the regiment was under the same commander.

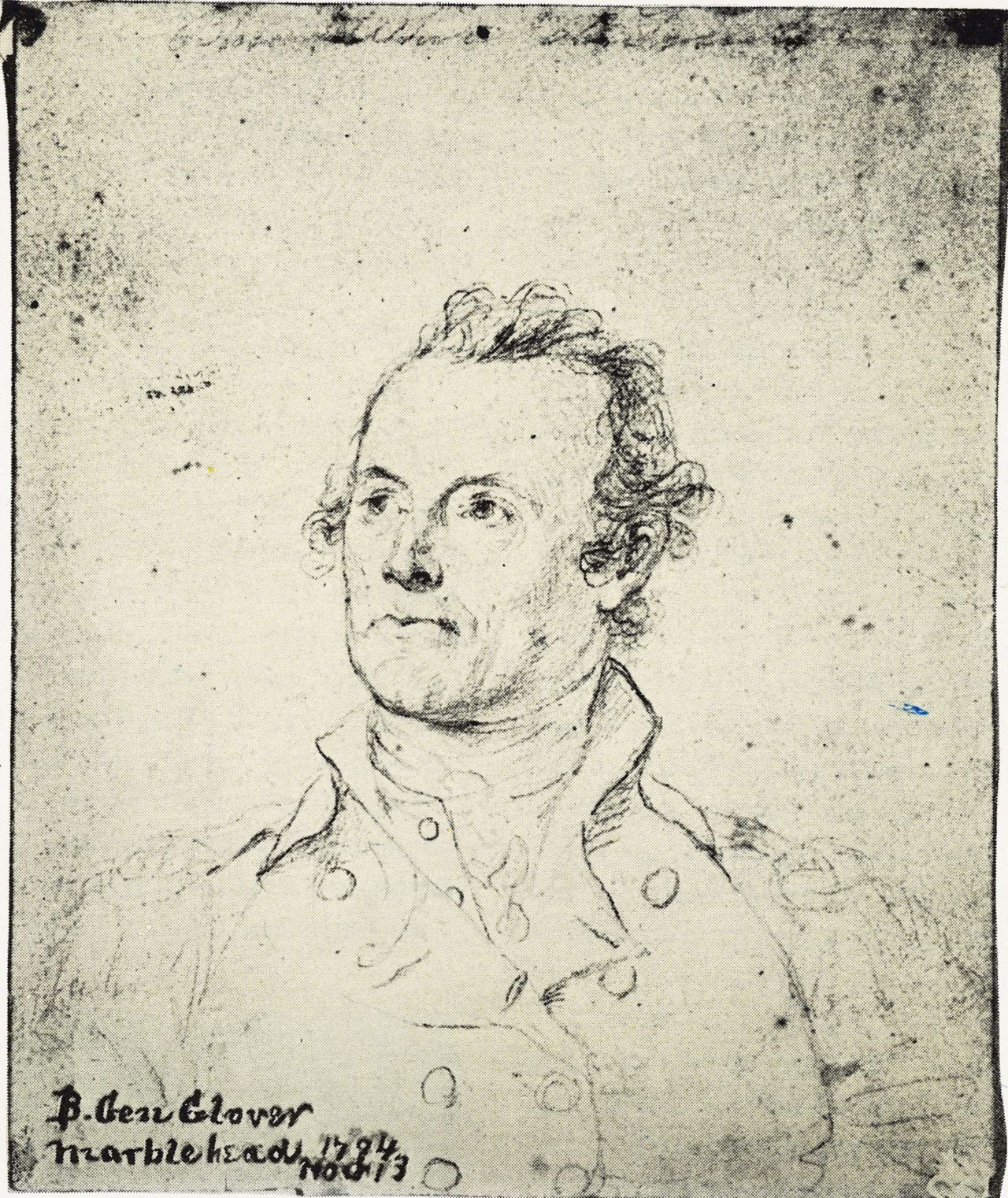

Colonel John Glover, the scrappy little man who led the outfit, was born the son of a housewright in nearby Salem and spent his early childhood there be fore moving to Marblehead. He was forty-three, the same age as George Washington, when war broke out. His handsome, finely chiseled features, sketched late in life by Colonel John Trumbull, show a broad, high forehead, clear, well-set eyes, and a long, broad nose. The outthrust jaw gives some hint of his toughness and determination. Although he was very short, Glover more than made up for his lack of height by his boundless energy.

Glover’s prewar career consisted of “shoes, ships and sealing wax.” He made his start as a simple cordwainer—a fact that prompted some wag to remark that he gave up his awl for his country when he entered the Army—but in fact Glover stayed at the shoemaker’s bench only long enough to earn a stake for a second career as a shipowner and merchant. In the lyGo’s at least three Glover vessels sailed to the Iberian Peninsula, the West Indies, and other colonies in America, inevitably he was drawn into the major Marblehead industry — the fisheries. This third business venture proved to be his most profitable. Shrewd, thrifty, and hard-working, he accumulated a tidy little fortune before the war began.

Although he had seen no combat, Glover was not a complete novice at the art of war. Behind him were considerable training and experience as an officer in the local militia. Appointed as an ensign in 1759, he advanced rapidly to captain lieutenant in 1762 and was made captain of a company in 1773. it is even probable that he received some schooling in military theory. Family tradition has it that Glover, William R. Lee, and other future officers of the Marblehead regiment formed a military association just prior to the war. They studied military theory and mastered the manual of arms, it is said, under a former sergeant in the British Army.

Glover not only studied but looked the part of a soldier. He was reputed to have been “the most finely dressed officer of the army at Cambridge,” and like that Essex County general of a later day, George S. Patton, he wore a pair of silver pistols into battle. He was also known to carry a Scottish broadsword and a bayonet imported from Genoa.

The Marbleheaders’ first assignment was to guard their home town, and after remaining there until June 21, 1775, the unit marched off to join the Army at Cambridge. For the next six months most of Glover’s men helped fill the lines in the siege of Boston, while others were assigned to special duties away from camp. Frequently, Marbleheaders were picked lor a post of honor to guard the headquarters of the commander in chief himself. One observer who saw Glover’s men at Cambridge described their offduty behavior as “most extravagantly excentric and sportful. … The men were not vitious, but all the time in motion, inventing and contriving amusements and tricks.”

However, it was as a naval unit rather than an army regiment that Glover and his men made their first significant contribution to the patriot cause. After Washington assumed command of the Army in July, 1775, he quickly foresaw the possibility of attacking the enemy on water as well as on land. The British Army was cooped up inside Boston and was forced to rely upon supplies brought in by sea. Congress had taken no steps to set up a navy, so Washington decided to send to sea a fleet of his own to cut off the enemy’s lines of supply. His commission said nothing about commanding sea forces, but Washington found a way to get around that. He detailed soldiers to serve as sailors aboard his ships, employed army officers as seagoing commanders, and used army funds to charter civilian vessels. To create what came to be known as Washington’s fleet, the general from Virginia found himself relying heavily upon the Marblehead seamen.

Washington picked Glover as one of the key officers to outfit and man the fleet, and the stocky Marbleheader made available his own trading schooner Hannah , converting her into an armed warship at his wharf in Beverly. When she sailed on her first cruise in September, 1775, the Hannah was commanded and manned by Marbleheaders from Glover’s regiment. By the end of October, Washington’s fleet had grown to six vessels—half of them with crews mustered from Glover’s unit.

Among their exploits as sea raiders was the Marbleheaders’ capture of the first important iminitions prize of the war. There was an acute shortage of powder at the time, and Washington hoped that ”… a fortunate Capture of an Ordinance Ship would give … an immediate turn to the Issue of the Campaign.” Some of Glover’s soldiers aboard the Lee made a “fortunate Capture” indeed when they took the British storeship Nancy in November. She was a floating arsenal carrying 2,000 muskets, 30 tons of musket balls, 30,000 round shot, 100,000 flints, and a monstrous brass mortar weighing 10,000 pounds. One American general claimed he could not have made out a better invoice if he had tried. Had he given such an order to the infant industries in America, it would have taken eighteen months to fill.

While their comrades served on shipboard, the rest of the regiment was soon employed on another mission associated with the sea. They were rushed to the Essex County coast in mid-December to forestall a threatened invasion by three British men-of-war. For the next seven months they manned the coastal defenses at Beverly, a major naval base for Washington’s fleet, guarding the little flotilla and its captured enemy vessels. Not until July so, 1776, did the regiment set out for New York to rejoin the main army that had left in March.

The regiment was not engaged in the Battle of Long Island that took place on August 27, 1776—a debacle that brought Washington’s army to the brink of disaster. When the smoke cleared, a tight little defensive perimeter barely two miles wide and a mile deep, near the Brooklyn Ferry, was the only territory on the island left in American hands, and had the British stormed the American lines immediately, they might have pushed the patriots into the bay. Instead, British General William Howe switched to siege tactics. With 15,000 men to Washington’s 9,000, he felt it was only a matter of time before the Americans would be overwhelmed.

As if matters on land were not desperate enough, the situation in the surrounding waters was worse. The British fleet had complete control of the sea and was maneuvering to enter the East River. If it succeeded, any retreat from Long Island by water was doomed. What was even more dangerous, the warships would be in position to shell the Brooklyn defenses from the rear. And since Washington had divided his forces between Long Island and Manhattan, possession of the East River by the British fleet would prevent them from joining, and allow Howe to deal with them piecemeal. The only thing that kept the enemy ships from reaching their objective was an unfavorable wind from the northeast. “When once the wind changed,” noted an English historian, “and the leading British frigates had … taken Brooklyn in the rear, the independence of the United States would have been indefinitely postponed. …”

Realizing his perilous predicament, Washington laid plans to evacuate his forces to Manhattan; but an amphibious retreat was no easy matter under the circumstances. As one American officer put it (overestimating the enemy’s numbers): To move so large a body of troops, with all their necessary appendages, across a river full a mile wide, with a rapid current, in face of a victorious, well disciplined army, nearly three times as numerous … and a fleet capable of stopping the navigation … seemed to present most formidable obstacles.

To overcome these obstacles, Washington called upon the seagoing skills of two regiments drawn from Essex County, Massachusetts.

Glover’s regiment had been hustled to Long Island in the early morning hours of August 28. After fighting all day and far into the night in the Brooklyn breastworks, the regiment was ordered to evacuate the shaken American army to Manhattan. Joined by Israel Hutchinson’s Twenty-seventh Massachusetts, an outfit made up largely of fishermen and sailors from Salem, Lynn, and Danvers, the Marbleheaders were to pit their nautical experience against three factors that might have made a shambles of the operation—time, tide, and wind.

Their race against time was bound to be a close one. The retreat had to be completed within the hours of darkness in a single night, for the British would discover the move at daylight and move in on the American lines immediately. Because midsummer nights are shortest, the patriots could hardly have picked a worse time of the year for their operation. Whether the two regiments could complete their task on time depended upon another variable—the elements. If wind conditions were not just right, sailing vessels could not be used; and if boats had to be rowed against the tide, trips would take longer.

Zero hour approached, and at about ten in the evening of August 29 the amphibious evacuation got under way. Glover’s men slipped stealthily out of the front lines and rendezvoused with Hutchinson’s men at the Brooklyn Ferry, where a motley fleet of small craft assembled from far and wide was awaiting them.

Navigating in inky darkness, a mile each way over an unfamiliar stretch of water, put the seamanship of the Massachusetts men to a stern test. No lights could be used, and the operation had to be carried out in the utmost quiet lest the enemy be alerted to what was going on. In spite of the silence and blackout conditions, the skilled mariners managed to nose their craft unerringly to the New York shore and to return for boatload after boatload of troops.

As long as weather conditions remained favorable the operation went smoothly; but the elements that had favored the Americans suddenly forsook them. Contrary winds sprang up shortly before midnight, and the ebb tide began to run so swiftly that even the experienced seamen could do nothing with their sailing craft. The use of sloops and similar sailing vessels had to be discontinued, which threatened the entire operation, since the number of rowboats on hand was not sufficient to carry off the rest of the men within the hours of darkness that remained. Fortunately the wind soon shifted, and the use of sailing craft was resumed.

Through the long, black hours the two regiments toiled feverishly, and the size of the force on Long Island dwindled. Keeping one eye on landmarks along the shore, with the other anxiously scanning the sky for the first signs of dawn, the seagoing soldiers managed to ferry nearly 9,000 men across the short stretch of water in a little less than nine hours.

Despite their best efforts, the mariners lost their race against time. When dawn came their job was unfinished, with part of the rear guard still on Long Island waiting to be evacuated. But once again, the elements granted the Americans a reprieve, just as the first enemy patrols appeared. One young captain who was among the last to be taken off described what happened: “Under the friendly cover of a thick fog, [we] reached the place of embarkation without annoyance from the enemy, who, had the morning been clear, would have seen what was going on, and been enabled to cut off the greater part of the rear. …” Fortunately, the British were caught flat-footed by Washington’s surprise move. When the first British troops poked their way into the abandoned breastworks the next morning, they were astonished to find them empty. In one of history’s most remarkable retreats, a whole American army had been whisked out of reach of the British by Massachusetts fishermen and sailors who put their civilian skills to military use.

That John Glover’s regiment could be equally effective on land was demonstrated shortly after the Long Island retreat. About noon on September 15, Howe launched a large-scale amphibious assault at Kip’s Bay—in the East River near present-day 34th Street—midway between the American forces stationed in New York City and at Harlem Heights. Securing a beachhead in this area was the first phase of Howe’s plan to push the patriots off Manhattan Island, and the picked troops that went ashore in this thrust were only part of the 32,000-man army under his command—the greatest expeditionary force ever assembled by Great Britain up to that time. When the landing parties hit the beaches, they were supported by gunfire from one of the largest war fleets ever seen in American waters.

Pounded by heavy shelling and threatened by enemy landing parties, the American troops at Kip’s Bay broke and ran, with the result that by the time Washington arrived at the battlefield, a frightened, disorganized horde was streaming to the rear.

Washington tried to halt them and to form a defensive line along the Post Road, near the present site of Grand Central Terminal. “Take the walls!” he cried, “Take the corn-field!”—but the panic-stricken troops bolted again at the sight of a small British advance party. Outraged by this display of cowardice, the commander in chief courted death by riding well out in front of his troops to rally the men, but in spite of him the soldiers continued their headlong flight.

At the height of the intense shelling, with the raking fire from British warships on the East River supported by enemy vessels on the Hudson, so that grapeshot and langrage whistled clear across the island, Glover’s regiment arrived on the scene, seemingly cool and calm in the face of the hot fire. Encountering the panic-stricken, broken militiamen, they stood firmly in the line, refusing to bolt for the rear.

Indeed, the men of Marblehead seem to have succeeded in checking the rout. What happened next was graphically described by an eyewitness: The officers of Glover’s regiment, one of the best corps in the service … immediately obliged the fugitive officers and men, equally, to turn into the ranks with the soldiers of Glover’s regiment, and obliged the trembling wretches to march back to the ground they had quitted.

This courageous act helped stave off what might have been a more serious disaster. If Howe had met with no resistance and marched due west to the Hudson, he could have cut off all the American troops under Israel Putnam, who were still in New York City. The action of Glover’s men at Kip’s Bay gave Putnam’s troops just enough time to escape the trap and join the main army at Harlem Heights.

It was on the receiving end of another British amphibious operation that Glover next encountered the enemy. After fighting his way up Manhattan, General Howe took a position on the northern part of the island in mid-September, but for nearly a month made no attempt to assault the American lines on Harlem Heights. Instead, he launched a series of amphibious landings in mid-October, leapfrogging up the Westehester County coast to outflank Washington’s army.

Glover had been given command of a small brigade of four Massachusetts regiments and sent to the vicinity of Eastchester, to guard against a possible enemy landing. When Howe’s force appeared off Pelham Bay on the morning of October 18, the future of the patriot cause rested for a time on Glover’s shoulders, for at the very hour Howe made ready to land, Washington’s main army was evacuating the Harlem lines to withdraw to White Plains. If Howe were able to brush Glover aside, he could plant the British army squarely in front of the retreating Americans. What Washington desperately needed on October 18 was enough time to extricate his forces.

When he arose on that fateful morning, Glover climbed a hill with his spyglass in hand to scan the horizon for some sign of the enemy. What he saw must have made him gasp. There in front of him stretched Howe’s amphibious force with boats—“upwards of two hundred sails”—carrying an estimated 4,000 British and German soldiers. Glover’s first reaction was to request orders from General Lee, his immediate superior. That such instructions never arrived is evident from Glover’s comment: “I would have given a thousand worlds to have had General Lee or some other experienced officer present, to direct or at least to approve of what I had done. …”

To oppose the invaders, Glover had 750 men and three fieldpieces. The odds against him were roughly five to one, yet as things turned out he did not even use his entire force. His own regiment he placed in reserve and never committed it to action, nor was he able to employ his artillery, since the rough terrain compelled him to leave his guns well to the rear.

Without delay, Glover turned out the brigade, and hurried down from his encampment to check the British. About halfway to their destination, thirty enemy skirmishers were encountered; coolly, the Marbleheader sent out an advance patrol to delay them while he deployed the rest of his brigade.

Glover’s battle plan was simple but effective. Stationing three regiments of his small command at staggered intervals, he covered both sides of Split Rock Road, which ran into the interior. The stone fences running along this lane and in the adjacent fields would, of necessity, force the enemy to advance down the narrow roadway, so Glover hid his men behind these ready-made fortifications. To break out into the open country to the west, the British and Germans would have to pass through a funnel of musketry.

To give his outnumbered units some measure of relief during the battle, Glover instructed each regimental commander to hold the enemy in check as long as possible, and then to fall back to a new position in the rear while the next unit in reserve took up the brunt of the fighting. The first regiment to contact the invaders was on the left side of the road, and it was expected that these troops would be able to retire unmolested because the next reserve unit was located on the right and thus would distract the attention of the enemy away from the retreat.

With his troops deployed, Glover rode back to his small advance patrol and ordered them to push forward. His forty-man force moved to within fifty yards of the hostile skirmishers and exchanged five hot rounds with the enemy. About that time the Americans suffered a few casualties, and the invaders, having received reinforcements, had closed to within thirty yards. Glover gave the order to fall back.

Scenting an easy victory, the enemy gave a shout and rushed in to follow up their advantage. When they were only thirty yards away, the most advanced regiment—Colonel Joseph Read’s Thirteenth Continental—sprang up from behind its stone fences and delivered a withering fire. Faced with a sheet of flame, the attackers broke ranks and ran.

For the next hour and a half there was a lull in the fighting, while British and Germans massed for an attack. Then on they came, hurling themselves at the American position as the deep roar of their six cannon shook the early morning air. Once again, from its forward position, Read’s regiment let loose a fierce fire, and the attackers shuddered to a halt. They promptly returned the fire with such “showers of musketry and cannon balls” that Glover had to order a retreat. The Thirteenth filed off, still protected by stone walls, until they were well past the point where the next unit—William Shepard’s Third—lay hidden on the opposite side of the road.

Once again the invaders made the fatal mistake of thinking they had smashed American resistance, and as they charged forward to finish off Read’s retreating regiment, up popped Shepard’s men with a deadly hail of bullets that stopped them in their tracks. The fiercest fighting of the day now took place. Posted behind a double stone wall, Shepard’s men, firing by “grand divisions,” kept up a steady stream of hot lead. Pumping a total of seventeen rounds per man into the enemy columns, they fought off repeated assaults, several times forcing the attackers to retreat.

By this time, however, the enemy had amassed too great a force to be denied any longer, so Glover ordered Shepard and Read to retreat to the rear of Loammi Baldwin’s fresh Twenty-sixth Regiment, which lay hidden behind a stone fence. Once more the game of tactical leapfrog was repeated, and the retreating regiments were covered as they fell back.

This process might have been repeated endlessly except that the Americans found themselves assailed by a flank attack around noon. Rather than risk the danger of being cut off, Glover decided to bring the engagement to a close. The three regiments were ordered back to rejoin his own Marblehead unit at the morning encampment. The retreat was covered by the three American cannon, and Glover reported, “The enemy halted, and played away their artillery at us, and we at them, till night, without any damage on our side, and but very little on theirs.” With the fall of darkness the exhausted Americans slipped off three miles to bivouac. Howe did not pursue them.

Glover’s spirited and stubborn all-day stand checked the British advance only temporarily. Howe’s dilatory strategy did the rest. For two days after the battle, the British general failed to follow up his advantage by pursuing the Americans into the interior. This delay gave Washington time to throw up a line of temporary redoubts behind the Bronx River to shield his retreating army from attack until he reached White Plains safely.

After fighting in White Plains during November, the men of Marblehead—now part of the brigade Glover continued to command—retreated across New Jersey in December to join Washington’s army. Although the men were not aware of it, they were headed for the last battle in which they would participate as a regiment, and appropriately, it was to be an amphibious operation.

Fighting in freezing weather was not to the British liking, and when his army had pushed the Americans beyond the banks of the Delaware, Howe set up a chain of posts in New Jersey and went into winter quarters. Two of these widely dispersed posts lay on the east side of the river at Trenton and Bordentown; the rest stretched out to the north and were more or less isolated.

Washington quickly grasped the flaw in the British defensive line-up. Each enemy post lay wide open for a surprise raid, and he worked out a daring plan to throw three separate forces across the Delaware on Christmas night to attack Trenton. Glover’s regiment was assigned to the main body because Washington was counting upon the Marbleheaders for a repeat performance of what they had done on Long Island. When the Trenton operation was being planned, the commander in chief is said to have asked Glover if his men could negotiate the river, and only after Glover replied that they could manage it did Washington proceed with his plan. Now it remained to be seen if the Marbleheader was as good as his word.

The first phase of the Battle of Trenton was a struggle not against the enemy, but against the elements. Christmas night brought with it a howling storm. A biting wind made the freezing waters of the Delaware choppy, and whipped the current to a swifter pace. As the weather turned ever colder, ice coated all the gear, so that the handling of oars and poles would be a slippery, treacherous task. A few days before there had been a thaw, and the river was littered with floating ice; but what probably bothered the Marbleheaders most was the unfamiliar craft they were given to man.

The Durham boats assigned to ferry the troops were used in peacetime for hauling iron, grain, and whiskey on the river; and they were ideal for this particular military operation because of their large size and light draft. They averaged sixty feet in length and had a beam of eight feet; one boat could transport an entire regiment of Washington’s under-strength little army. Even when fully loaded, they drew only two feet of water, thus enabling the troops to get in close to shore. They came equipped with oars and poles and even carried masts for sails. Pointed at both ends and looking like oversized canoes, these somewhat unwieldy fresh-water craft must have seemed strange to Glover’s salt-water sailors.

As soon as dusk fell, the boats, which had been concealed from’view, were brought down to McKonkey’s Ferry, which lay nine miles up the river opposite Trenton. At about the same time, Washington’s men back at camp reluctantly left the warmth of their small fires to trek to the point of embarkation.

The Delaware at this point was barely a thousand feet wide, but Glover’s men were forced to call upon all their skill to navigate the short span. Great chunks of ice came churning downstream like white torpedoes to smash against the heavily burdened boats. As they ground to a halt alongside the craft, each slab had to be shoved aside by poles or oars to enable the boats to continue their passage.

As if conditions on the treacherous river were not bad enough, it began to snow about eleven, destroying what little visibility there had been. Peering into the blinding storm, Glover’s men strained their eyes to pick out ice floes from the mass of white that whirled across their vision. Back on the west bank, young, stout Henry Knox bellowed orders to the troops loading aboard the Durham boats. No doubt he was given this assignment because his booming bass voice could be heard above the river’s roar, and because the success of the expedition would hinge largely on the cannon in his charge. Artillery was the bad-weather arm of the American army, since muskets could not be relied upon once the priming powder got wet, and as soon as it began to snow, Knox’s guns took on greater importance. Glover’s men succeeded in ferrying the eighteen heavy howitzers and guns, but only after a phenomenal effort. As Knox himself noted so aptly, ”… perseverance accomplished what at first seemed impossible.”

John Glover’s regiment with its superb seamen was worth ten regiments that night. Without these men there might never have been a Battle of Trenton, for the two other forces that comprised the attack turned back in despair, leaving the issue squarely in the hands of the 2,400 troops led by Washington himself. Overcoming obstacles that had proved insuperable to two other task forces, the Marblehead regiment ferried men, horses, and cannon across the Delaware without a single loss. What was even more important, they placed Washington’s force in a position to launch a knockout blow against the unsuspecting Hessians.

It was nearly three in the morning before Glover’s command finished its task, and another hour was required to get the men in marching formation. In the brigade were five regiments of infantry and a battery of artillery, whose guns were destined to play an important role in the coming battle.

As Glover’s troops trudged wearily toward the enemy, exposure and fatigue began to take their toll. Having faced the wind and snow for hours during the backbreaking trips to and fro across the Delaware, some of the men began to succumb to the bitter cold. One of Glover’s lieutenants became so numb he fell by the roadside in the slush and snow. He lay there with the snow covering his inert form, and would have died had not one of his comrades in the rear ranks stumbled over him.

Arms as well as men were affected by the intense cold. Glover’s son John, commanding one of the Marblehead companies, discovered that some of the regiment’s arms—like those of many other units—were so wet they could not be fired. The word was passed up the chain of command to Washington; back came his grim and determined order to “advance and charge.” The bayonets in Glover’s regiments were put to good use that morning;.

After marching about five miles toward Trenton, Washington’s force was split into two divisions. Glover’s brigade joined General John Sullivan’s command that was sent down the River Road that ran roughly parallel to the Delaware, while Washington and Nathanael Greene led the other division to the upper route known as the Pennington Road. Washington’s plan was to approach Trenton from opposite directions and by a sudden, double-pronged assault to smash into the town before the Hessians could rally any resistance.

A’though the hazardous river crossing had thrown Washington’s timetable off by nearly four hours, the simultaneous attack came off almost perfectly. Greene’s division opened on the enemy shortly after eight o’clock. Three minutes later Sullivan’s division, with Glover’s brigade near the head of the column, ran into the first advance Hessian picket post. A small New Jersey detachment drove in the picket, and Glover’s brigade took up the chase and pursued the retreating guards pell-mell into town.

The rest of the attack was brilliantly executed. In the upper part of town, Greene’s division raced down Pennington Road to the intersection of King and Queen streets, where they planted some cannon to sweep the two main thoroughfares of Trenton. Greene then threw some troops further east to prevent any Hessian retreat in that direction. The only escape route remaining open was the bridge at Assunpink Creek in the lower end of town.

Glover’s brigade entered the lower part of Trenton and, driving hard to the southeast, reached Queen Street, where they came upon part of a Hessian regiment retreating under fire from the cannon at the head of the street. Glover’s men promptly opened up, placing the enemy between two fires. Some of the Hessians fled over the Assunpink bridge and disappeared in the direction of Bordentown. Glover’s men dashed after them but stopped after seizing the bridge. Wheeling his artillery into position on the high ground south of the creek and to the left of the bridge, Glover bottled up the last escape corridor.

The battle came to an end quickly. Remnants of two Hessian regiments surrendered to Greene’s troops, who had blocked their attempt to break out to the north and northeast. To the southeast, elements of one enemy unit, the Knyphausen Regiment, headed for the bridge to make good their escape. Discovering Glover’s men there, the Hessians fell back to the east along a path that ran just above the Assunpink, hoping to find a ford across the creek. Pinned down by fire from Glover’s artillery on their flank, faced with another American brigade to their front, and with their backs against the cold, deep waters of the Assunpink, most of the Knyphausen Regiment surrendered.

By ferrying Washington’s forces across the Delaware, Glover’s men had made the attack on Trenton possible; by cutting off the enemy’s last escape route, they made success certain. They had one more contribution to make. Some 950 Germans had surrendered, and Washington decided to move them across the river immediately. Once again he turned to Glover’s men, who ferried the prisoners and spoils back over the Delaware.

It was nearly dark that December afternoon before the first prisoners were taken over, and recrossing the river took longer because there were more trips to make. On one of them an entire load of Hessian officers was nearly lost as a Durham boat capsized. By the time the last of the American troops were ferried back to the Pennsylvania side, the night of the twenty-sixth was all but gone.

Glover’s men were on the verge of exhaustion. For nearly thirty-six hours, under the worst possible conditions, they had been rowing and poling boats, marching and fighting as infantry, then rowing and poling once again.

The victory at Trenton had an enormous psychological effect upon the Army and the nation. As Trevelyan wrote in The American Revolution : ”… it may be doubted whether so small a number of men were ever employed so short a space of time with greater or more lasting results upon the history of the world.” In view of the major role played by Glover’s men in fashioning the victory, it seems altogether fitting that the statue of a Marblehead private guards the base of the battle monument at Trenton.

Paradoxically, most men of the organization left the Army in the hour of their glory. Privateering, that endemic disease of all mariners in the Revolution, took the largest toll.

Even Glover quit the service for a short time, although for other reasons. His prolonged absence from business had put his family into desperate financial straits, and his wife’s health was so poor that she was soon to die. He went back to Marblehead to attend to personal affairs, and when Congress promoted him to brigadier general in February, 1777, he declined the commission. Only after Washington wrote him a flattering and persuasive letter did Glover change his mind. Returning to the Army in June, 1777, he led a brigade through the Saratoga and Rhode Island campaigns, performed garrison duty, and mustered recruits before retiring from active service in 1782.

With the passing of the Marblehead regiment, the patriot army lost one of its most colorful units. There is no truth in the old legend that these men were the first official members of the Marine Corps; but it is certain that their role as a kind of sea infantry set a tradition for American marines in later wars. Whenever American fighting men have participated in amphibious warfare, they have carried on in the footsteps of John Glover and his famous Marblehead regiment of the Revolution.