A menu for a 1779 New England Thanksgiving included dishes from turkey and venison to pumpkin pie.

-

November 2020

Volume65Issue7

Editor's Note: The nine Thanksgiving recipes linked to below are reprinted from The American Heritage Cookbook, which was published in eight editions from 1964 to the mid-1980s.

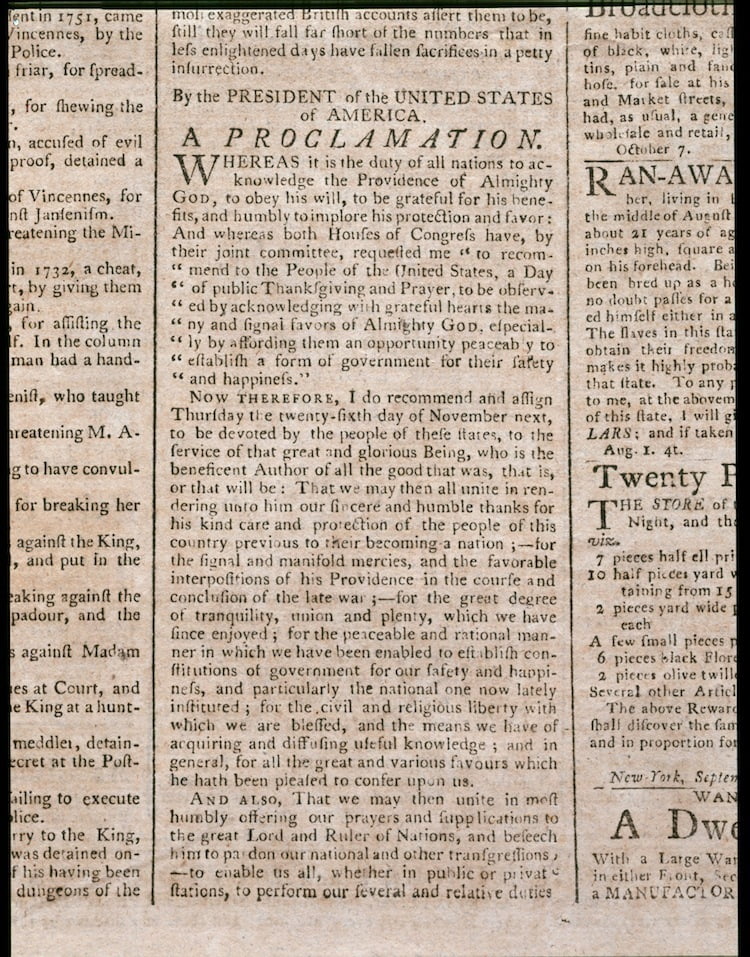

This menu for a New England Thanksgiving dinner is taken from a letter written in 1779 by Juliana Smith to her “Dear Cousin Betsey.”

- Haunch of Venison

- Roast Chine of Pork

- Roast Turkey

- Pigeon Pasties

- Roast Goose

- Squash

- Onions in Cream

- Cauliflower

- Potatoes

- Raw Celery

- Mincemeat Pie

- Pumpkin Pie

- Apple Pie*

- Indian Pudding*

- Plum Pudding*

- Cider

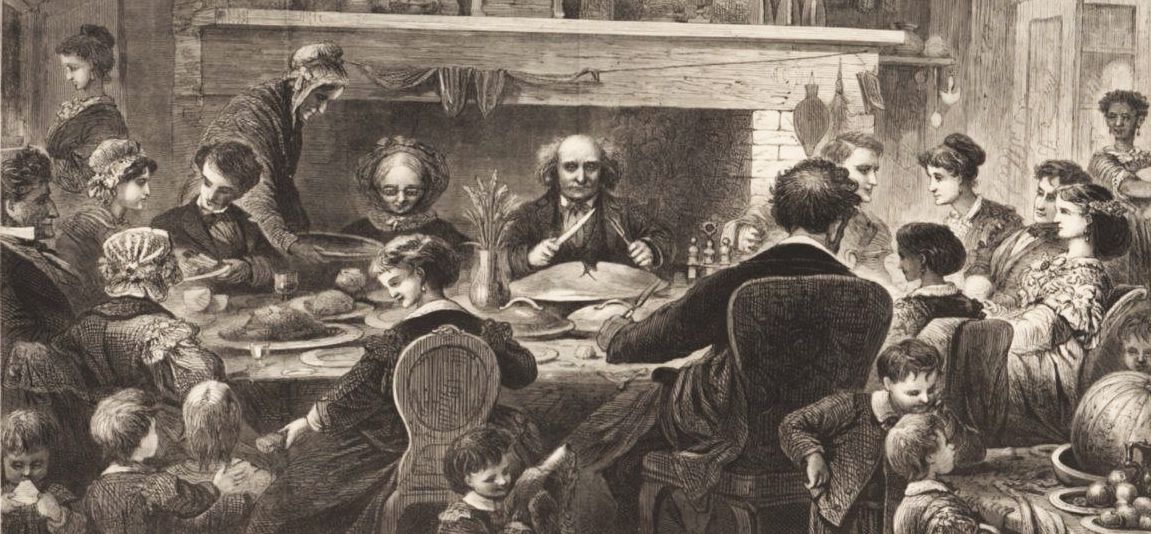

As Thanksgiving Day approached, Grandmother Smith, “who is sometimes a little desponding of Spirit as you well know, did her best to persuade us that it would be better to make it a Day of Fasting & Prayer in view of the Wickedness of our Friends & the Vileness of our Enemies, I am sure you can hear Grandmother say that and see her shake her cap border.... But my dear Father brought her to a more proper frame of Mind, so that by the time the Day came she was ready to enjoy it almost as well as Grandmother Worthington did, & she, you will remember, always sees the bright side."

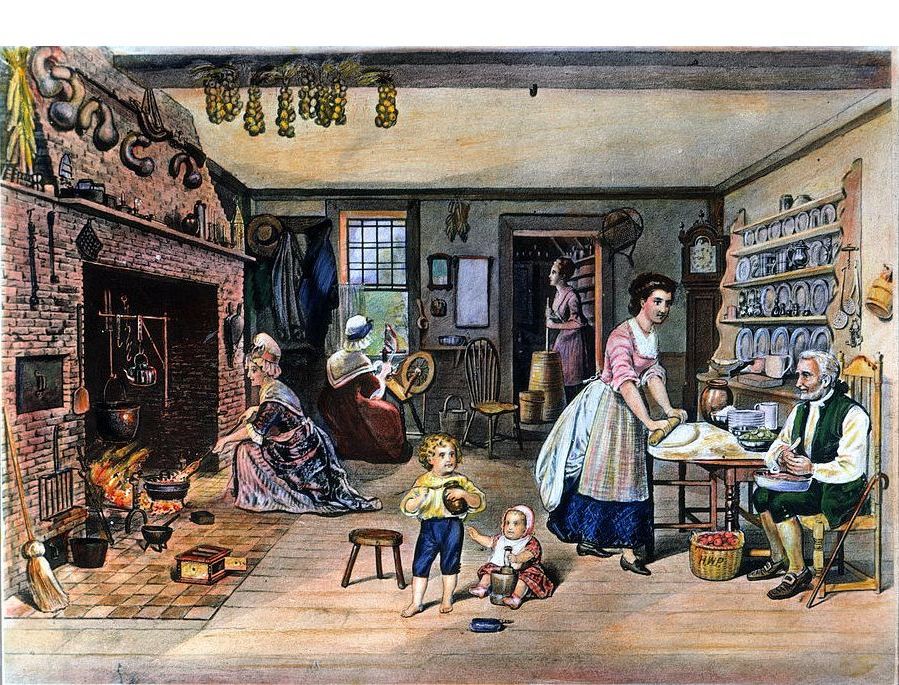

While it would be difficult to set forth a single “traditional" Thanksgiving menu, the preparations related by Juliana Smith that went into this dinner were certainly typical of early New England Thanksgivings.

“This year it was Uncle Simeon's turn to have the dinner at his house, but of course we all helped them as they help us when it is our turn, & there is always enough for us all to do. All the baking of pies & cakes was done at our house & we had the big oven heated & filled twice each day for three days before it was all done. & everything was GOOD, though we did have to do without some things that ought to be used. Neither Love nor (paper) Money could buy Raisins, but our good red cherries dried without the pits, did almost as well & happily Uncle Simeon still had some spices in store. The tables were set in the Dining Hall and even that big room had no space to spare when we were all seated.”

Apparently roast beef was part of the traditional menu for this family, but “of course we could have no Roast Beef. None of us have tasted Beef this three years back as it all must go to the Army, & too little they get, poor fellows. But, Nayquittymaw's Hunters were able to get us a fine red Deer, so that we had a good haunch of Venisson on each Table.”

There was an abundance of vegetables on the table, including "one which I do not believe you have yet seen. Uncle Simeon had imported the Seede from England just before the War began & only this Year was there enough for Table use. It is called Sellery & you eat it without cooking.” Cider was served instead of wine, with the explanation that Uncle Simeon was saving his cask "for the sick.” Juliana added that “The Pumpkin Pies, Apple Tarts & big Indian Puddings lacked for nothing save Appetite by the time we had got round to them.”

Counting the Reverend Mr. Smith, his wife, two grandmothers, and the six Livingstons from next door, there were forty people at the dinner. “Uncle Simeon was in his best mood, and you know how good that is! He kept both Tables in a roar of laughter with his droll stories of the days when he was studying medicine in Edinborough, & afterwards he & Father & Uncle Paul joined in singing Hymns & Ballads. You know how fine their voices go together. Then we all sang a Hymn & afterwards my dear Father led us in prayer, remembering all Absent Friends...”We did not rise from the Table until it was quite dark, & then when the dishes had been cleared away we all got round the fire as close as we could, & cracked nuts, & sang songs & told stories. At least some told & others listened. You know nobody can exceed the two Grandmothers at telling tales of all the things they have seen themselves, & repeating those of the early years in New England …”