Our first president spoke about abolishing slavery, but couldn’t manage without the unpaid labor of hundreds of people at Mount Vernon.

-

June 2021

Volume66Issue4

Editor's Note: David O. Stewart is the author of the recently-released George Washington: The Political Rise of America’s Founding Father, which has been awarded the History Prize of the Society of the Cincinnati. He has written numerous books of history and articles in American Heritage and other publications.

George Washington led the American fight for freedom, but, from 1760 until his death in 1799 he managed some 700 enslaved people on Mount Vernon. Forty-seven of them escaped, but he recovered many of them. Washington recognized that punishing slaves “often produces evils which are worse than the disease,” yet even after announcing an end to whipping, he again employed the practice.

“If the Negros will not do their duty by fair means,” he wrote to one manager, “they must be compelled.” Enslaved people stole from him, set his property on fire, and avoided work by breaking his tools and feigning illness.

Washington only gradually, and inconsistently, came to repudiate slavery. In 1774, when he was forty-two, he joined his first anti-slavery statement as the prime sponsor of the Fairfax Resolves. One resolution demanded the end of slave imports, “a wicked cruel, and unnatural trade.”

Anti-slavery sentiment was awakening. In 1771 and 1774, the Massachusetts Assembly voted for abolition, but the royal governor vetoed both bills. Slaves entering Rhode Island and Connecticut were proclaimed free. By the end of the Revolutionary War, every state banned slave imports, though only Massachusetts and Pennsylvania prohibited owning slaves.

A French traveler in 1782 observed that Virginians “are constantly talking about abolishing slavery.” Such statements eventually came from Washington, though never consistently.

He initially excluded black soldiers from the Continental Army, but roughly 5000 African Americans served in it. Washington accepted a Rhode Island battalion of African American soldiers who would be freed at war’s end. He later ordered that black and white Rhode Islanders serve in an integrated unit. Yet he rejected raising a battalion of African Americans in South Carolina and Georgia, fearing the venture would foment southern unrest.

Washington honored black soldiers’ sacrifices. He could hardly justify taking their liberty after they had suffered and died for his. Yet his inconsistency on slavery persisted. He instructed his farm manager not to sell enslaved people against their wishes. He then offered to acquire land if the seller would accept payment in Negroes “of whom I every day long more and more to get clear of.”

After the war, the Marquis de Lafayette urged Washington to free his negroes, proposing a shared plantation cultivated by freed slaves. Washington demurred. The enslaved should be freed gradually, he insisted, “by legislative authority,” as in Northern states.

Washington’s path on slavery veered between principle and self-interest. In 1786, he rejected a transaction involving enslaved people, insisting he would not “hurt the feelings of those unhappy people by a separation of man and wife, or of families,” but then accepted six unattached male slaves. He wrote that he wanted no more enslaved people, but would purchase a bricklayer if no family would be fractured.

Washington claimed to support abolition. When Quakers sued to enforce a Pennsylvania emancipation statute, Washington insisted that “there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see a plan for the abolition of it [slavery].” His commitment, however, was tepid, conditional, and always private. He called for ending slavery “by slow, sure, and imperceptible degrees”; imperceptible abolition resembles no abolition at all.

In 1785, Washington would not sign a petition urging gradual emancipation in Virginia, but promised that “if the Assembly took it into consideration, [he] would signify his sentiments to the Assembly by letter.” He sent no such letter.

His public silence likely flowed from the calculation that publicly embracing abolition would do little good while harming himself. Abolitionists were a small minority, while even gradual emancipation terrified many slaveowners and would erase Washington’s large investment in enslaved workers.

Washington’s ambivalence about slavery emerged again in 1791, when he learned that enslaved workers at his Philadelphia residence could claim freedom after living in Pennsylvania for six months. He directed his secretary, Tobias Lear, to evade the law by sending out of state any who might soon qualify for freedom, and to act “under pretext that may deceive both them and the public.” Lear complied, expressing “the fullest confidence that [the slaves] will at some future period be liberated.”

Perhaps the truest passage Washington ever wrote about slavery came in 1794: “I do not like to think, much less talk about it.”

See also “10 Facts About Washington & Slavery” on the Mount Vernon website

As early as 1788, calling his ownership of slaves as “the only unavoidable subject of regret,” he sought a plan to end it without courting financial ruin.

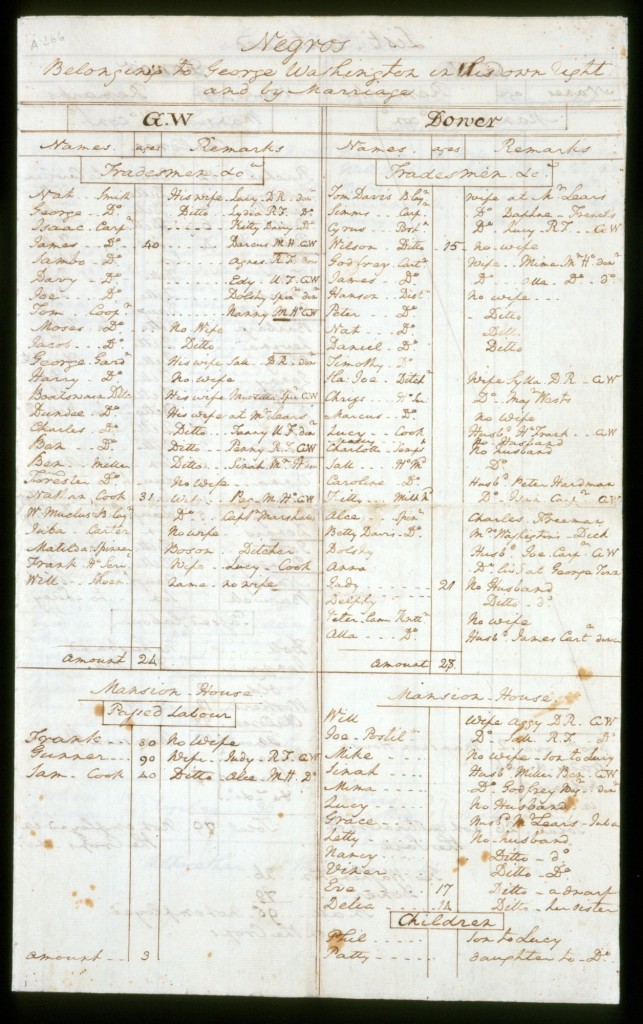

The project was not simple. Washington’s lands contained two groups of enslaved workers. He could emancipate the hundred or so he owned outright, but more of the Mount Vernon slaves were “dower” slaves, owned by the estate of Martha’s first husband. Martha’s grandchildren were entitled to that human property after Martha’s death. Under law, George and Martha had to preserve the value of those slaves for the grandchildren’s benefit.

To free the dower slaves, Washington had to purchase them from the estate at fair prices. He wanted to do so because many dower slaves had married those owned by Washington. Freeing only his slaves would divide those families. He needed cash he could raise only from his lands in the west and Northern Virginia, and at Mount Vernon.

In late 1793, Washington offered to lease out four of his five Mount Vernon farms, noting that he expected to “remove my Negroes.” In a follow-up, he explained that new tenants would not assume responsibility for his slaves, as he “had something better in view for them.” A new tenant could hire the slaves “as he would do any other laborers.” His “most powerful” motive, Washington explained, was “to liberate a certain species of property which I possess, very repugnantly to my own feelings.”

In early 1796, Washington again tried to sell and lease his lands. A 4,000-word advertisement never mentioned enslaved workers. A separate list of lease terms clarified that Washington did not wish slaves to work the lands, but his commitment was wobbly: “Although the admission of slaves with the tenants will not be absolutely prohibited; it would, nevertheless, be a pleasing circumstance to exclude them.”

Liberating the slaves was important, but he had to pay the grandchildren while supporting himself and those formerly enslaved people who were too young or too old to work. When Washington disclosed the plan, he wrote that “One great object is to separate the Negros from the land” while preserving the “tranquility with a certain income.” Yet he waffled on emancipation, considering leasing enslaved people to new tenants.

Enough slaveowners were freeing their human property that by 1800, free blacks numbered 20,000 in Virginia. Other slaveowners flirted with the idea of shipping enslaved workers “back to Africa.” Washington never indulged the fantasy of mass deportation, yet his plans never ripened. No tenants leased his farms; no one bought his western lands.

And Washington remained responsible for managing more than 300 enslaved people. The situation wore on him. While still president, he predicted that slaves would become “a very troublesome species of property.” Learning of a runaway, Washington responded, “these elopements will be MUCH MORE, before they are LESS frequent.”

In 1799, he made his gloomiest prediction. Slavery, he feared, could destroy the union: “I can clearly foresee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union.” Immediate abolition would fracture the nation, but a gradual approach was impossible in southern states.

In June 1799, armed with a census of Mount Vernon’s enslaved people, Washington wrote a new will. Its commanding language directed that after he and Martha died, the slaves that he owned should be freed. Older ones would be supported, younger ones educated. He died six months later; thereafter, Martha emancipated the Washington slaves.

When Washington began to plan to free his slaves, he said his course “could not I hope be displeasing to the justice of the Creator.”

His final action came very late and was incomplete. Yet even halfway measures may have a quality of righteousness.