Our nation is free because, 250 years ago, brave men and women fought a war to establish the independence of the United States and created a system of government to protect the freedom of its citizens.

-

Spring 2024

Volume69Issue2

Editor’s Note: Jack Warren is an historian and editor-in-chief of The American Crisis, a journal of history and commentary. He edited the presidential papers of George Washington while on the faculty of the University of Virginia and was for many years the executive director of The Society of the Cincinnati. This essay is adapted from his new book, Freedom: The Enduring Importance of the American Revolution (Lyons Press). Mr. Warren wrote the book, he explains, to combat the cynicism of our time: “The idealism of the revolution,” he concludes, “is the foundation of our freedom and the hope of people who long for freedom in every part of the world.”

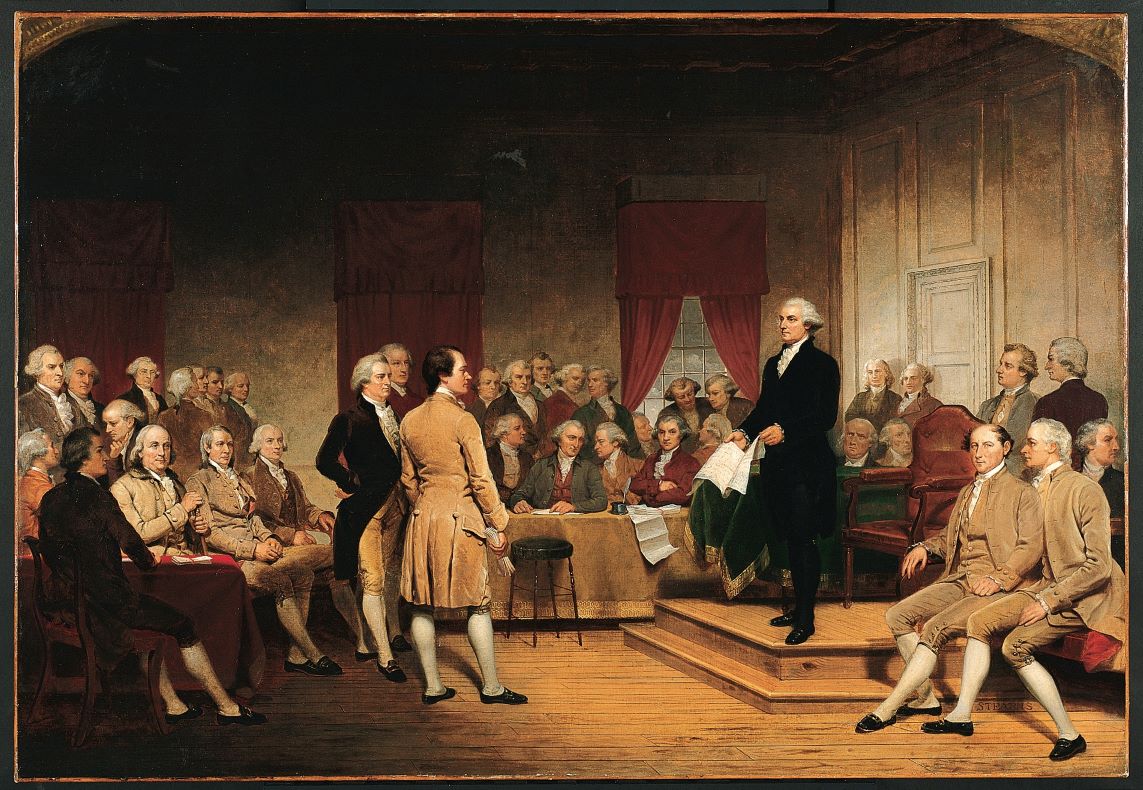

The American Revolution is our national epic — the story of remarkable men and women who secured their independence in a war of liberation, established a republican system of government, and became a united people, with a shared history and national identity. It is a great story, full of courageous people who risked their lives to create a new nation dedicated to freedom. All Americans, whatever their background, can take pride in their achievement.

The story of the American Revolution begins in our colonial past, when freedom as we understand it was not yet imagined. The people of colonial British America lived in a society characterized by deep and pervasive inequalities. Women were subordinate to men, their talents stifled, their natural rights ignored, and their civil rights denied. Indentured servitude was common, and enslavement was practiced throughout the colonies, as it was through much of the Atlantic world.

Some British Americans – men who published newspaper essays and pamphlets and left their papers for us to read – were proud to claim “the rights of Englishmen,” not understanding the limited, tenuous, and fragile nature of those rights. They were subjects of a king, not citizens of a republic. The wealthy and privileged among them had few opportunities to participate in government. Women, the poor, and the enslaved had none at all. Colonial British Americans enjoyed few of the rights we take for granted, including freedom of expression and of religion. They lived in a world of grotesque injustice, darkness, and oppression.

The American Revolution laid the foundation of a free society. It did not destroy all existing inequalities, but it opened new opportunities for millions of Americans, including unprecedented chances to participate in public life. The revolution made the injustice of slavery a subject of national debate that did not end until slavery was extinguished. No sooner had the revolutionaries declared that all men are created equal than women began to assert that same equality and to demand the same inalienable rights so proudly asserted as the rights of men. The revolutionaries framed constitutions for their government based on the idea of natural rights, which were defined and protected by constitutional law. They created a nation dedicated, not to the interests of kings and aristocrats, but to the interests of ordinary people.

Nothing like it had ever existed.

The revolution was shaped by high principles and low ones, by imperial politics, dynastic rivalries, ambition, greed, personal loyalties, patriotism, demographic growth, social and economic changes, cultural developments, British stubbornness, and American anxieties. It was shaped by conflicting interests between Britain and America, between regions within America, between families, and between individuals. It was shaped by religion, ethnicity, and race, as well as by tensions between rich and poor. It was shaped, perhaps above all else, by the aspirations of ordinary people to make fulfilling lives for themselves and their families, to be secure in their possessions, safe in their homes, free to worship as they wished, and to improve their lives by taking advantage of opportunities that seemed to lie within their grasp.

No one of these factors, nor any specific combination of them, can properly be said to have caused the revolution. An event so vast is simply too complex to assign it neatly to particular causes.

Although we can never know the causes of the American Revolution with precision, we can see very clearly the most important consequences of it. They are simply too large and important to miss, and are so clearly related to the revolution that they cannot be traced to any other sequence of events. Every educated American should understand and appreciate them.

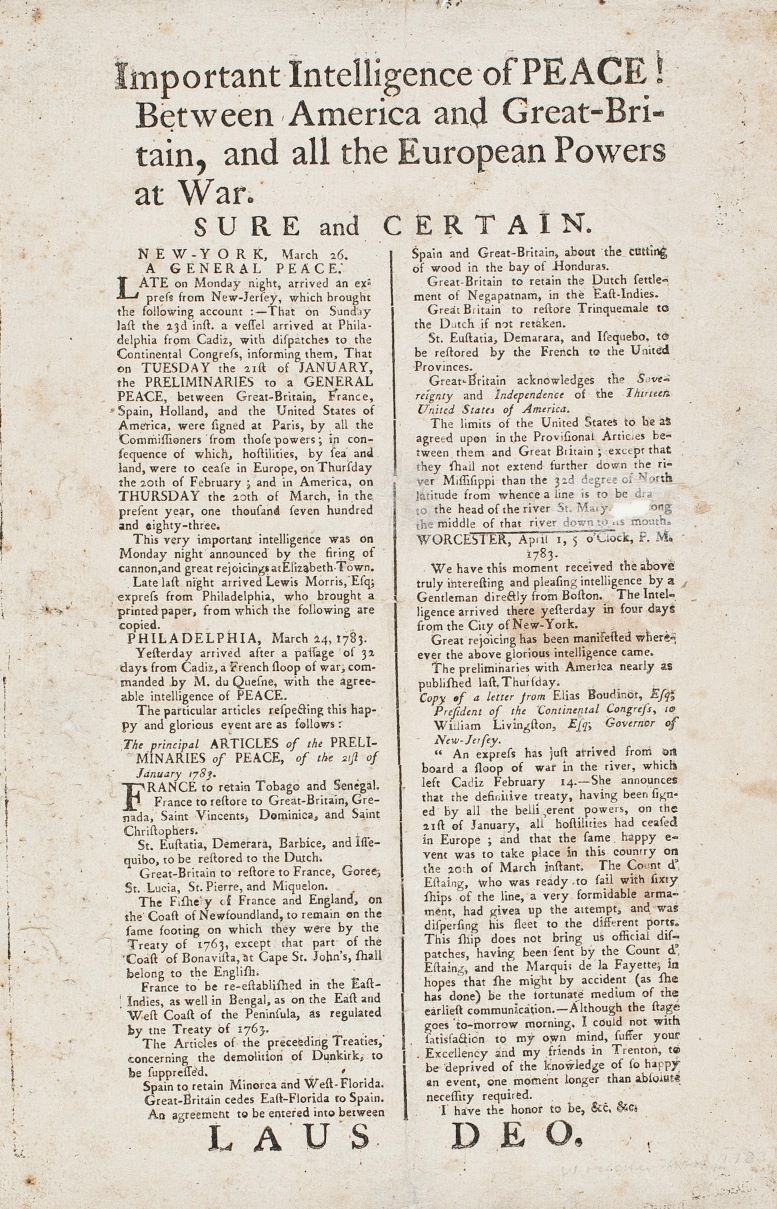

First, the American Revolution secured the independence of the United States from the dominion of Great Britain, and separated it from the British empire. While it is altogether possible that the 13 colonies would have become independent during the 19th or 20th century, as other British colonies did, the resulting nation would certainly have been very different from the one that emerged, independent, from the Revolutionary War.

The United States was the first nation in modern times to achieve its independence in a national war of liberation and the first to explain its reasons and its aims in a declaration of independence, a model adopted by national-liberation movements in dozens of countries over the last 250 years.

Second, the American Revolution established a republic, with a government dedicated to the interests of ordinary people, rather than of kings and aristocrats. The United States was the first large republic since ancient times and the first one to emerge from the revolutions that rocked the Atlantic world, from South America to Eastern Europe, through the middle of the 19th century.

The American Revolution influenced, to varying degrees, all of the subsequent Atlantic revolutions, most of which led to the establishment of republican governments, though some of those republics did not endure. The American republic has endured, due in part to the resilience of the federal constitution, which was the product of more than a decade of debate about the fundamental principles of republican government.

Today, most of the world’s nations are at least nominal republics, due, in no small way, to the success of the American republic.

Third, the American Revolution created American national identity, a sense of community based on a shared history and culture, mutual experience, and belief in a common destiny. The revolution drew together the 13 colonies, each with its own history and individual identity, first in resistance to new imperial regulations and taxes, then in rebellion, and finally, in a shared struggle for independence. Americans inevitably reduced the complex, chaotic, and violent experiences of the revolution into a narrative of national origins, a story with heroes and villains, of epic struggles and personal sacrifices.

This narrative is not properly described as a national myth, because the characters and events in it, unlike the mythic figures and imaginary events celebrated by older cultures, were mostly real. Some of the deeds attributed to those characters were exaggerated and others were fabricated, usually to illustrate some very real quality for which the subject was admired and held up for emulation.

The revolutionaries themselves, mindful of their role as founders of the nation, helped create this common narrative, as well as symbols to represent national ideals and aspirations.

American national identity has been expanded and enriched by the shared experiences of two centuries of national life, but those experiences were shaped by the legacy of the revolution and are mostly incomprehensible without reference to the revolution. The unprecedented movement of people, money, and information in the modern world has created a global marketplace of goods, services, and ideas that has diluted the hold of national identity on many people, but no global identity has yet emerged to replace it; nor does this seem likely to happen any time in the foreseeable future.

Fourth, the American Revolution committed the new nation to ideals of liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and responsible citizenship, and made them the basis of a new political order. None of these ideals was new or originated with Americans. They were all rooted in the philosophy of ancient Greece and Rome, and had been discussed, debated, and enlarged by creative political thinkers beginning in the Renaissance. The political writers and philosophers of the 18th-century Enlightenment disagreed about many things, but all of them imagined that a just political order would be based on these ideals.

What those writers and philosophers imagined, the American Revolution created – a nation in which the ideals of liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and responsible citizenship are the basis of law and the foundation of a free society.

The revolutionary generation did not complete the work of creating a truly free society, which requires overcoming layers of social injustice, exploitation, and other forms of institutionalized oppression that have accumulated over many centuries, as well as eliminating the ignorance, bigotry, and greed that support them.

One of the fundamental challenges of a political order based on the principles of universal right is that it empowers ignorant, bigoted, callous, selfish, and greedy people in the same way it empowers the wise and virtuous. For this reason, political progress in free societies can be painfully, frustratingly slow, with periods of energetic change interspersed with periods of inaction or even retreat. The wisest of our revolutionaries understood this, and anticipated that creating a truly free society would take many generations. The flaw lies not in our revolutionary beginnings or ideals, but in human nature. Perseverance alone is the answer.

Our independence, our republic, our national identity, and our commitment to the high ideals that form the basis of our public life are not simply the consequences of the revolution, to be embalmed in our history books. They are living legacies of that revolution, more important now, as we face the challenges of a world demanding change, than ever before. Without understanding them, we find our history incomprehensible, our present confused, and our future dark.

Understanding them, we recognize our common origins, appreciate our present challenges, and can successfully advocate for the revolutionary ideals that are the foundation for the future happiness of the world.