We can better understand how Washington thought by piecing together clues that have remained hidden in the books he once owned.

-

Special Issue - George Washington Prize 2018

Volume63Issue2

A hundred years ago, Ezra Pound criticized American history textbooks for ignoring Washington's intellect; Pound's critique still applies. More often than not, Washington has been seen as a shelf-filler, someone who decorated his home with books but seldom read them fully or deeply. Here's an alternate theory: though George Washington never assembled a great library in the manner of, say, Benjamin Franklin or Thomas Jefferson, he did amass an impressive and diverse collection of books that he read closely and carefully, and that significantly influenced his thought and action.

The image of George Washington as a man of letters is much different from the accepted image of George Washington as a man of action. This new view may take some getting used to, but the story of Washington's life of the mind, pieced together with some archival detective work, can be quite exciting.

When I started to write the first intellectual biography of Washington, a historian tried to discourage me, claiming the documentary materials simply do not exist to tell such a story. Unlike so many of the other Founding Fathers, he argued, Washington left little record of his intellectual life. Benjamin Franklin wrote a famous autobiography, among many other occasional pamphlets, essays, and letters, all of which dramatize his lifelong interest in reading and writing. Thomas Jefferson's voluminous correspondence and his massive library provide access to his mind. And John Adams recorded his agreements and disagreements with authors in the margins of his books.

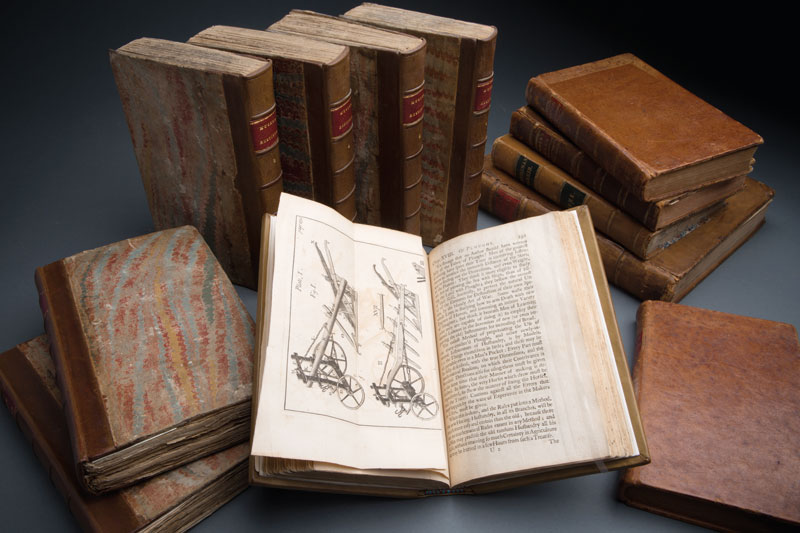

Though Washington's surviving comments about books and reading are not nearly as extensive as those of some other Founding Fathers, he did leave many different types of evidence that, in the aggregate, can help reconstruct his life of the mind. Although his library was widely dispersed during the nineteenth century, many of his books do survive. The Boston Athenaeum holds the single largest collection of books formerly in his possession. Additional books survive at Mount Vernon, the Firestone Library at Princeton University, the Houghton Library at Harvard University, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the Library of Congress, the Lilly Library at Indiana University, the Morgan Library, the New York Public Library, the Virginia Historical Society. I examined as many books from Washington's original as I could for clues to his thinking.

With the notable exception of his copy of James Monroe's View of the Conduct of the Executive of the United States, Washington's surviving books contain few notes in the margins, but he did occasionally write in his books. Most of the time he did so to correct typographical errors, but sometimes his marginal notes reveal how he read. Occasionally his notes in one book indicate other books he read. The fact that Washington wrote in his books has gone largely unnoticed, because uncovering these notes requires work that some find tedious. One must examine the surviving books meticulously, turning over one page after another in search of the slightest pencil marks showing that Washington did read the volumes that bear his bookplate.

There is also evidence to identify books from Washington's library that do not survive. Mainly, it comes in the form of library catalogues. Washington himself compiled two such catalogues, which not only list what books he had at Mount Vernon but also demonstrate his level of bibliographical expertise. Lund Washington, his cousin and plantation manager, compiled a list of books at Mount Vernon toward the end of the Revolutionary War. Washington's library was inventoried with his estate after his death. When many of his books went up for sale in the nineteenth century, the booksellers described them in considerable detail. All these various catalogues provide much additional information about Washington's books.

Washington not only owned and read books, he also wrote and published them. Washington was a reluctant author, but sometimes his professional responsibilities compelled him to publish what he wrote. Occasionally editors, both friends and enemies, took charge and edited Washington's writings, especially his letters, for publication, and we can glean valuable information from them as well.

As a writer, Washington was at his best when penning letters. Like any good letter writer, he shaped his tone and persona to suit individual readers. Though he seldom discussed his reading with correspondents, sometimes he did provide bookish advice, especially when it came to recommending what military manuals to read or what agricultural manuals were useful. Washington's correspondence, which fills dozens of volumes in the standard edition of his papers, contains numerous references that shed light on his books and reading. His literary allusions are often subtle, and many of them have gone unnoticed previously.

Washington also kept a diary through much of his life, but his individual diary entries are frustratingly brief. He says where he was and what he did, but seldom does he reveal the inner man. He rarely mentions what he read or what he was thinking. Every once in a while, he does provide a tantalizing clue indicating the importance of one particular book or another. For instance, he used a book of farriery in his library to try and save the life of a favorite horse that had broken its leg.

Washington filled many blank quires, or folded sheets of paper, with notes he took while reading. Some of these notes come from practical manuals. Others come from books of history and travel. Several of these notebooks survive at the Library of Congress. Amounting to a total of nearly nine hundred pages, Washington's manuscript notes supply a wealth of information about his reading process. Other notebooks survive in fragmented form. The owner of one such notebook disbound it and distributed its individual holograph leaves to friends. Now only three leaves from the original notebook survive.

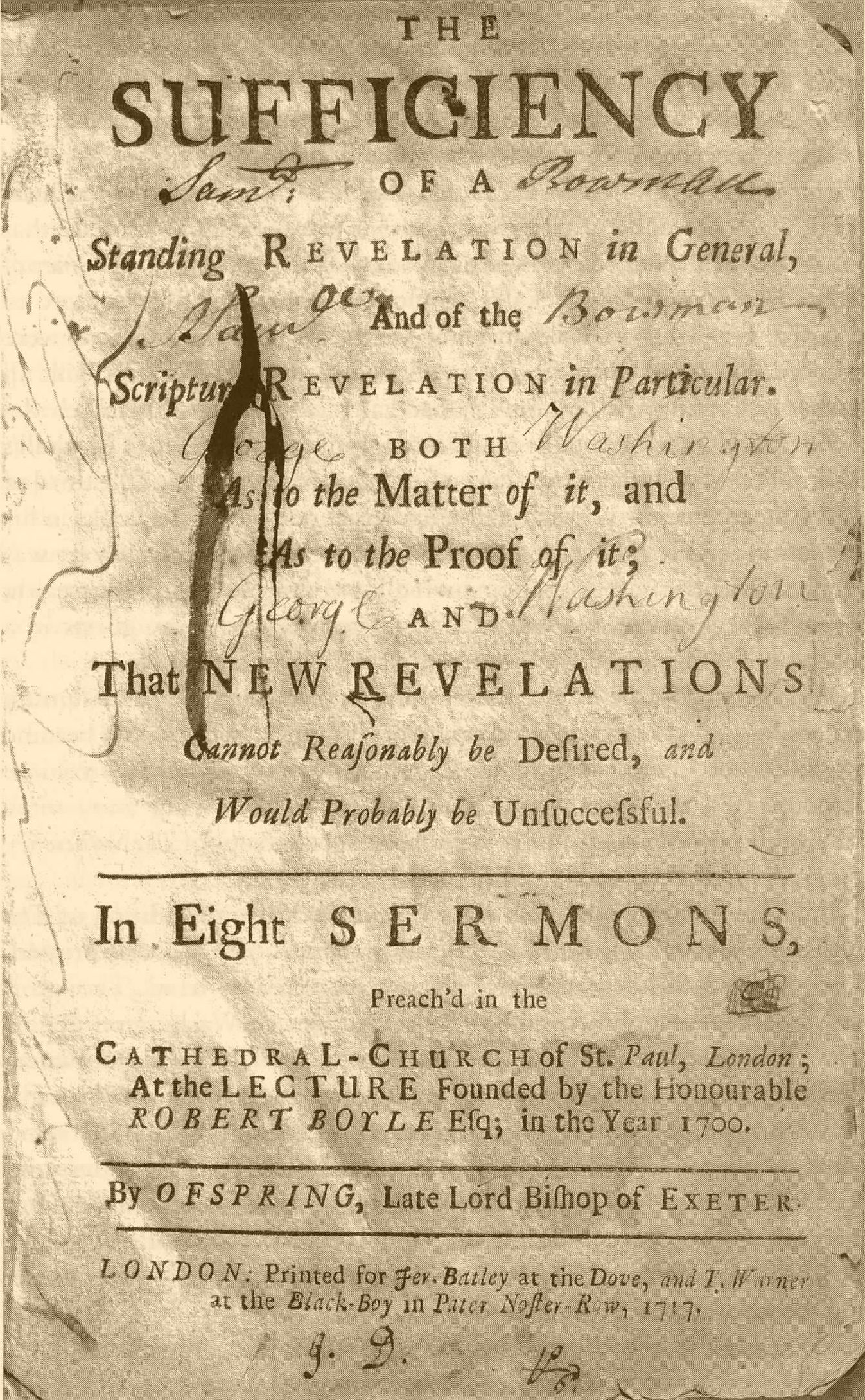

George Washington understood the power of books early in life. He started forming a personal library as a boy and added to it all his life. He treasured the books he owned, later commissioning an engraved armorial bookplate to paste into their covers. He often signed the title pages of his books, his autographs providing additional marks of ownership. The changes Washington's autograph underwent as he matured help date several early acquisitions. According to the handwriting style of their title-page inscriptions, some of the books that survive from Washington's library date from his adolescence. Other books he acquired in his late teens, when he deliberately changed his handwriting style. In adulthood Washington's signature became fairly consistent, so it is more difficult to date subsequent acquisitions based solely on handwriting style. But the books Washington obtained in his youth provide a rich, yet largely untapped, resource for understanding his life, his mind, and his spirit.

Washington's earliest known autograph survives on the title page of The Sufficiency of a Standing Revelation in General, and of the Scripture Revelation in Particular, a set of sermons given by the Reverend Dr. Offspring Blackall in 1700. Washington's signature in this volume dates from around 1741, the year he turned nine, too young to understand its meanings. But handwritten notes in other books he owned suggests that Washington read The Sufficiency of a Standing Revelation in his late teens.

Though Washington read much during his formative years, from magazine verse to mathematical textbooks to stories of travel and adventure, devotional literature shaped the man he would become. Like many other religious books in his library, The Sufficiency of a Standing Revelation emphasizes meditation as a devotional practice. Blackall tells his readers: "What I would desire of you is; that you would frequently think of those things which you profess to believe, that you would meditate much and often thereupon, that you would seriously consider the meaning thereof."

The meditative practice defined and delineated by Blackall and other religious authors strongly influenced Washington's thought process. That influence did not happen instantly. When Washington began his military career, a dangerous impetuosity guided his battlefield decisions. But slowly he came to understand how religious meditation could apply to realms outside religion. As military commander, legislator, and president, Washington would establish a reputation for long, slow, judicious reasoning. The decision-making process he demonstrated as an adult hearkens back to the books he read in boyhood.

Washington took good care of Blackall's book. His copy, bound in handsome yet unassuming tooled sheepskin, marks the earliest known beginning of what would become his 18th-century gentleman's library. The survival of this volume demonstrates its importance to Washington. While giving away some other books from his personal collection, he kept his copy of Blackall all his life.

Like many other Virginians who came of age in the middle third of the eighteenth century, Washington had great respect for the books in his possession—with good reason. In colonial America a personal library was a hallmark of the proper gentleman. It allowed him to display his wealth, his cultural prestige, and his intellectual prowess, to show guests in a subtle and sophisticated way who he was and what he thought.

Washington found out early the importance of books for military officers. A letter from William Fairfax asserts that Washington owned a copy of Julius Caesar's Commentaries as a young man, and the figure of speech Caesar used just before crossing the Rubicon—"The die is cast"—became a favorite of Washington’s. He also owned a copy of Quintus Curtius's History of the Wars of Alexander the Great at the time. Fairfax reported that the young officer could hardly stop talking about the exploits of both Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great. Years later Washington would order busts of Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar to adorn Mount Vernon.

Quintus Curtius's History of the Wars of Alexander the Great could teach Washington much about leadership. It demonstrates the personal qualities a great leader requires: decisiveness, flexibility, camaraderie, clemency, a mind that enjoys wrestling with problems, practicality, resolution in the face of danger, self-control, a sense of efficiency, and a strong will.

Caesar's Commentaries – written as a narrative, not a practical manual – could nonetheless be read as a military guide. It provides more useful detail about strategy than Curtius's History of Alexander. Caesar's story of his military exploits in Gaul emphasizes the importance of engineering: building bridges, constructing fortifications, erecting siege towers, making roads. Yet Caesar was a pragmatist. Good roads are important, but an army should only build them when they have the time. In the heat of combat, speed, stealth, and surprise are vital elements of success.

Efficient communication is also essential. Furthermore, a commander needs to understand the mindset of his men. Sufficient provisions are necessary not only for assuring the welfare of the troops but also for securing their loyalty. Courage is important; discipline is more important. Soldiers should not let courage outstrip discipline. A commander must take several steps to understand the enemy: analyze its tactics, scrutinize its fortifications, and survey its territory. Flexibility is key. He must be willing to adjust his strategy to adapt to the enemy, the terrain, and the weather.

But, by the start of the Seven Years' War, Washington recognized serious gaps in his military knowledge and sought to deepen his knowledge of the art of war. In late 1755, some months after taking part in General Braddock's disastrous campaign against the French, Washington ordered a copy of Humphrey Bland's Treatise of Military Discipline, the standard manual of drill and discipline in the British army. During the middle third of the eighteenth century, it was the duty of every young British officer to read "Bland," or, as it was sometimes called, "Old Humphrey."

During the American Revolution, Washington urged his officers to read books. Captain Johann Ewald, a Hessian officer who served on the British side with the Field Jager Corps, recalled: "I was sometimes astonished when American baggage fell into our hands during that war to see how every wretched knapsack, in which were only a few shirts and a pair of torn breeches, would be filled up with military books."

Seeing so many American knapsacks filled with so many military manuals, Captain Ewald made some general conclusions about the officers of the Continental Army, especially compared with their British counterparts. Ewald named the titles of a number of European military books he had found among the Americans, some of which turned up, by his estimate, a hundred times. Impressed with their desire for knowledge on the battlefield, Ewald concluded that the American soldiers "studied the art of war while in camp, which was not the case with the opponents of the Americans, whose portmanteaus were rather filled with bags of hair-powder, boxes of sweet-smelling pomatum, cards (instead of maps), and then, often, on top of all, some novels or stage plays."

True to habit, Washington turned to books to prepare for his critical role as the nation’s first president. He had read closely the essays of James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay in The Federalist and been a strong advocate for them, helping with reprinting and distributing copies of the essays. The famous Lansdowne portrait that Gilbert Stuart painted of Washington during his presidency reinforces the importance of books in his intellectual and political life. There are several in the painting, some with clearly legible titles, and like other objects shown they possess rich symbolic power. Two volumes appear atop the table. The Journal of Congress stands upright, with The Federalist propped against it. The image suggests the ideas that The Federalist embodies provide the philosophical and ideological support necessary for Congress to operate. Together the two give President Washington the power and authority to rule the nation with fairness and justice.

A corner of the tablecloth is turned up to reveal additional books beneath the table. Their appearance and position reinforce the importance of books in Washington's life. Before taking the presidential oath of office, Washington had read widely and learned much from his reading, but he had no need to display his knowledge ostentatiously. He wears his erudition lightly, keeping it hidden like a set of books beneath a cloth-covered table. He does not need to show off his learning. He knows it is there. He has synthesized his reading and can now use it to govern the nation.

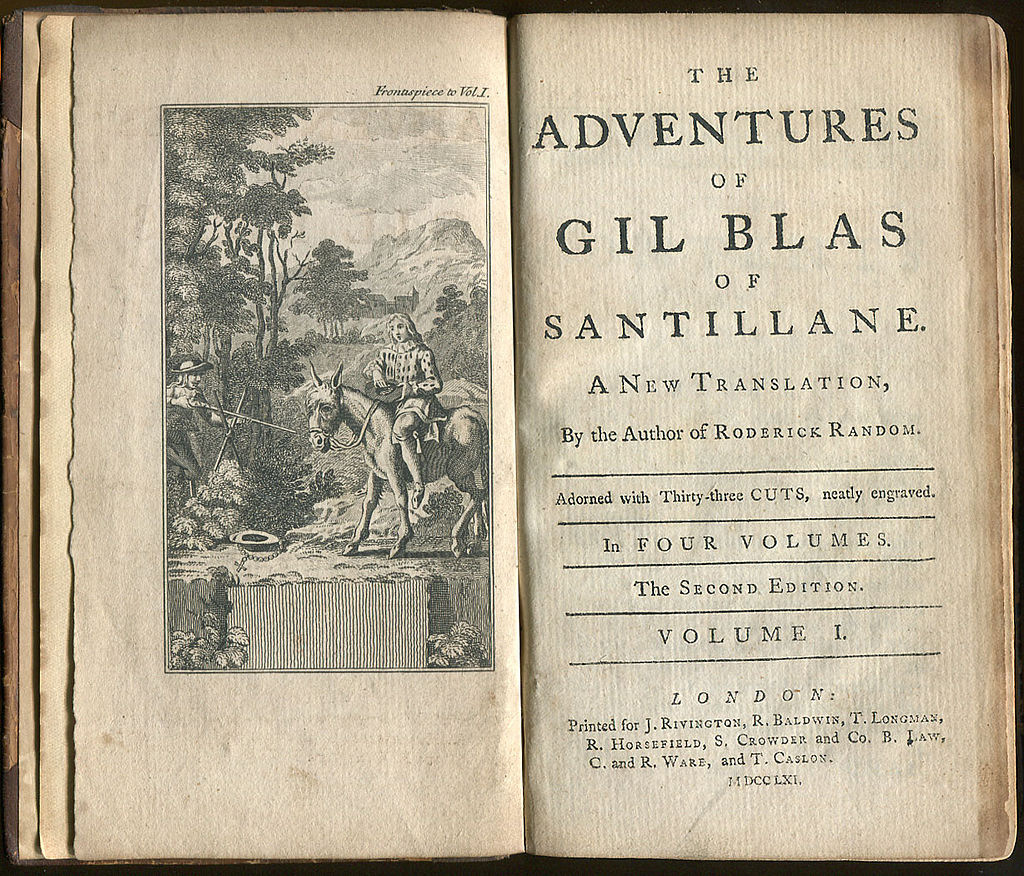

Interestingly, Washington not only read The Federalist to prepare for political life, he also read the likes of Don Quixote, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, John Buncle, and Gil Blas. By including fiction, Washington would seem to have been engaged in two very different literary activities, but perhaps the two types of reading are not unrelated. The world of the picaresque novel is filled with all types of people from the lowest blackguards to leaders of church and state. Gil Blas starts his adventures in a cave full of robbers who force him to live the life of a highway thief. After escaping their clutches, he encounters many other people, some of whom occupy positions of respect and authority. Gil Blas learns that highwaymen and statesmen are not so different after all. Leaders of church and state are no less liable to indulge their desire for money and power than cave-dwelling robbers.

In its broadest perspective, the picaresque novel is a comment on human nature, revealing the greed, thirst for power, and need for control that are inherent aspects of the human condition. Government itself can be interpreted similarly.

In Federalist No. 51, James Madison asks, "But what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature?" He followed this rhetorical question with a poignant observation: "If men were angels, no government would be necessary." The picaresque novel portrays a world that is out of control, one where people grab all the money and power and control they can. The US Constitution, as The Federalist clarifies, provides a way to control human nature, to guard against the abuse of power and channel it to the common good.

When George Washington died in 1799, his estate had to be inventoried. As was common in the 18th century, the books were catalogued volume by volume. His library contained more than a thousand volumes, plus many more pamphlets. A man's library, it has been said, is a window to his soul. Because so many of the books Washington acquired during the last decade and a half of his life were presentation copies, his library may reveal less about the inner man than, say, the libraries of Thomas Jefferson or Benjamin Franklin. Yet the inventory of Washington's library that was taken upon his death does permit some conclusions.

Washington's library reflects his practical bent. Most of the books he acquired late in life were highly useful works. Dictionaries and encyclopedias provided references he could dip into whenever he needed specific information. His collection of military books, perhaps the finest in Revolutionary America, seems remarkably purposeful. He did not read military books as a hobby. He expanded his military library during times of war but added few volumes to it in times of peace. His collection of law books, tiny compared with the typical library of the eighteenth-century Virginia gentleman, consisted mainly of practical works too. When Washington wrote the landmark will that freed his slaves, he did so without consulting an attorney: his law books alone gave him guidance. The few theoretical works in his legal collection treated the laws of nature and nations, which contained the fundamental theories that formed the basis of the US government.

History and travel, two of the largest subject areas in Washington's library at Mount Vernon, proved ideal for recreational reading. Washington accepted the long-standing notion that literature must both delight and instruct. Travels offered exciting, action-packed narratives that nonetheless informed readers about geography and customs from around the world. Histories presented narratives of the past that could be used to shape the future. They let pragmatic readers like Washington know what to emulate and what to avoid. Biographies, in turn, presented patterns of behavior that readers could use to shape their own.

The narrative aspect of travels and histories enhanced their readability, but another type of narrative, the novel, was largely absent from the library shelves at Mount Vernon. Washington did own Don Quixote, Gil Blas, and the picaresque English novels they inspired, but, otherwise, his library contained few novels. Washington had trouble reading fiction, that is, narratives lacking useful information. Agricultural treatises like those John Sinclair sent to him never seemed to tire Washington.

Viewed as literature, the novel and the agricultural treatise are polar opposites. The novel presents a narrative but lacks practical information; the agricultural treatise contains practical information but has no narrative. Or does it? Though agricultural treatises may lack any explicit narratives, they do have implicit ones. Forward-thinking readers like Washington could read an agricultural treatise with an eye toward what would happen once its schemes were put into practice. Instead of telling what has already happened, it foreshadows what will happen.

Like many of the other books in George Washington's life, they project a vision for the future.