American resistance to British authority developed with stunning speed 250 years ago in response to George III’s inflexibility.

-

November/December 2024

Volume69Issue5

Editor’s Note: This is the ninth essay in American Heritage by Joseph J. Ellis, author of a dozen critically acclaimed books on the early years of the Republic including Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in History. Portions of this essay appeared in his recent book, The Cause: The American Revolution and its Discontents, 1773-1783.

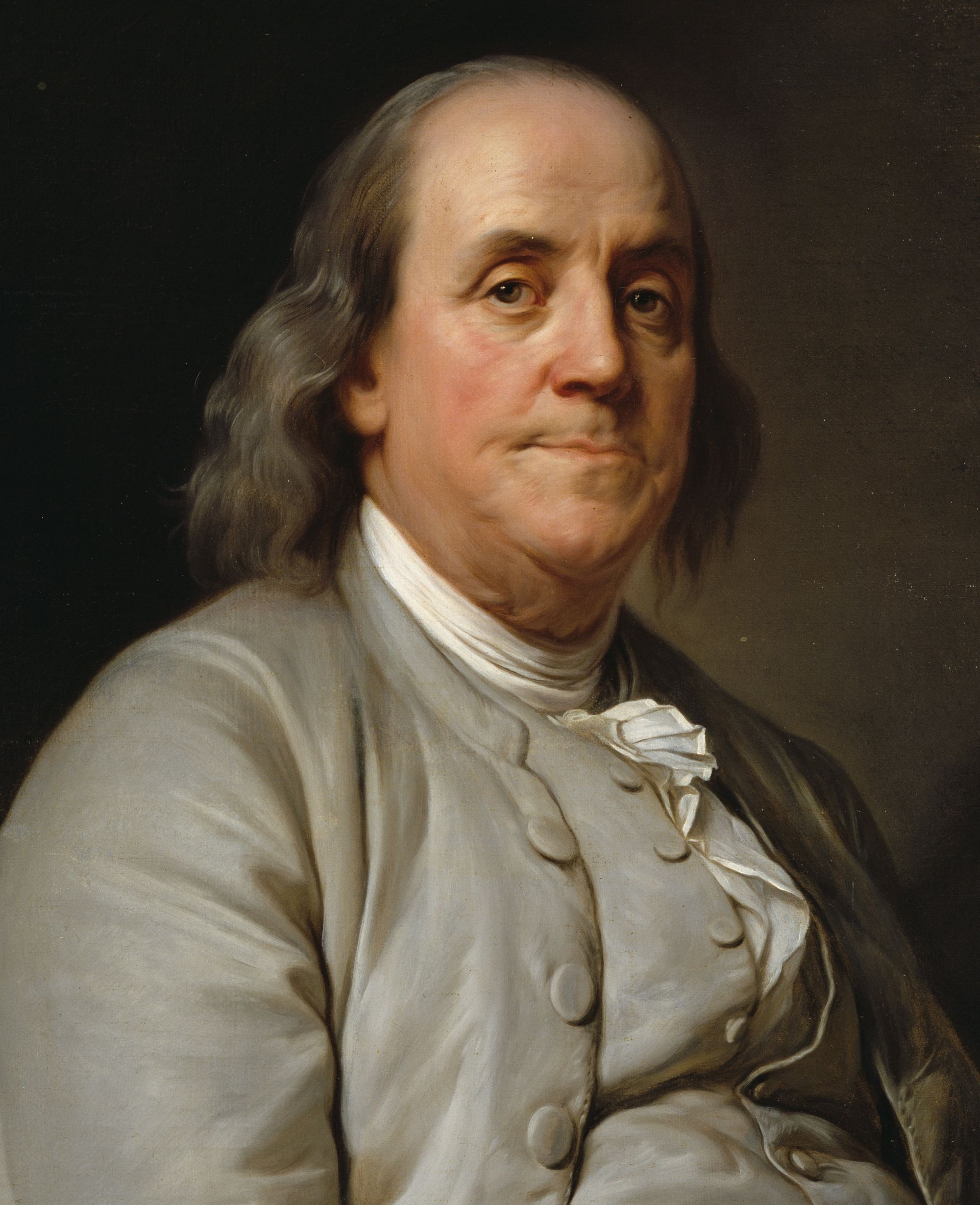

There was surely a mischievous twinkle in his eye when Benjamin Franklin made his outrageous prediction. It came at the end of his Observations on the Increase of Mankind (1751), which provided demographic evidence showing that the population of the British colonies in North America was doubling every twenty to twenty-five years, a rate over twice as fast as the population of England.

This led Franklin to imagine a future Anglo-American empire, about a century later, in which the capital had moved from London to somewhere on the Susquehanna River in western Pennsylvania. Intriguingly, although Franklin’s reading of the long-term demographic and economic trends allowed him to foresee the looming power of a large continent over a small island, he could not imagine a wholly independent American nation. He presumed that America’s expanding significance would occur within the protective shield of the British Empire.

Franklin was describing the eventual emergence of what came to be called the British Commonwealth, with the United States cast in the role subsequently played by Canada and Australia. Given his vantage point in 1751, and his presumption that long-term change would occur gradually in response to America’s sheer geographic and demographic size, that is how American history could have happened. But American independence occurred on a revolutionary rather than evolutionary schedule, in the crucible of a highly compressed political crisis that generated ideas and institutions which continue to define what has become the world’s oldest and most enduring nation-sized republic.

The imperial crisis that culminated in American independence had its origins in the Treaty of Paris (1763) after the enormous British triumph in the Seven Years’ War with France (in America called the French and Indian War). ln addition to several French possessions in Africa and the Caribbean, the great prize Britain acquired was the former French empire in North America. This included all the land from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River, between Canada and the Floridas. The Treaty of Paris effectively laid the global foundation for the first British Empire, with its base in North America.

There was a palpable and broadly shared sense that Great Britain was entering a new chapter in its history that was simultaneously glorious and ominous. The most experienced and informed British student of American colonial policy at the time, Thomas Pownall, sensed a dramatic shift in the atmosphere, “a general idea of some revolution of events, of something new arising in the world.” Pownall’s experience as a royal governor in several colonies made him more fully aware of the unprecedented size and scale of the American theater and the management problems it posed. “There is a universal apprehension,” Pownall warned rather vaguely, “of some new crisis forming.”

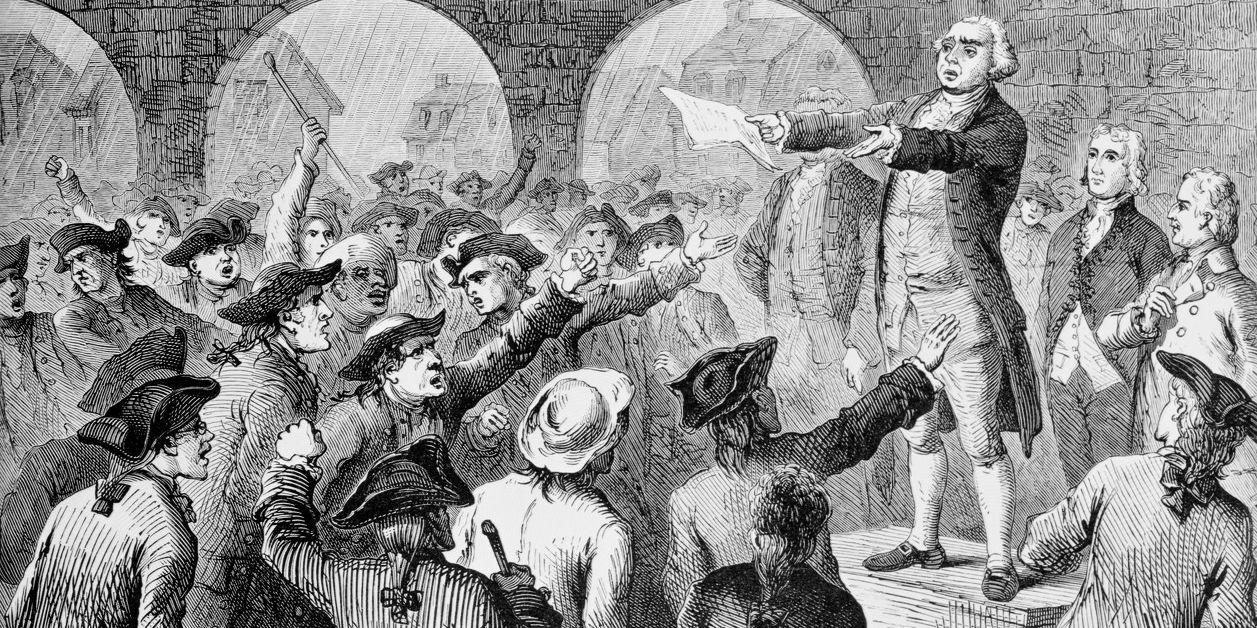

What has impressed several generations of historians is the stunning speed with which the well-framed resistance to British authority seeped down to the county, town, and local level, effectively rendering enforcement of the new taxes and duties impossible. Almost instantaneously, American colonists created a communications network that generated the first truly national dialogue in American history.

If only in retrospect, there were several preexistent conditions that provided a foundation for the emerging revolutionary dialogue. The American colonies happened to enjoy the highest literacy rate in the world, approaching 90 percent in New England. By 1770 there were also nearly 150 newspapers in circulation, which routinely reprinted stories from other publications in distant precincts.

The emergence of the pamphlet as a cheap, readily accessible vehicle for authors, often styling themselves “Cato” or “Publius,” offered the perfect instrument for what we might regard as early-day blogs. In effect, despite the primitive conditions including the sheer nonexistence of roads, especially south of the Potomac, ideas could travel on a virtual highway for the printed word that defied distance.

New England led the way in what came to be called “circular letters” and “committees of correspondence.” Massachusetts, under the leadership of Samuel Adams, created a routinized communications network connecting all the roughly two hundred towns and villages of the colony to headquarters back in Boston. If John Dickinson was the preeminent figure in shaping the American argument in the 1760s, Samuel Adams was the dominant figure in orchestrating the spread of that message to the countryside and beyond. The groundswell of opposition to Parliament’s imperial initiative had rendered the entire tax program just as ludicrously inoperable as the ill-fated Proclamation of 1763.

Several shifts in British ministries – from George Grenville, to the Marquis of Rockingham, to Lord North – created what was effectively a bimodal policy: Parliament would repeat the specific enactments of the imperial principle but retain its commitment to the principle itself. Thus, the Board of Trade simply stopped trying to collect the duties mandated by the Sugar and Townshend Acts, then, after a highly contested vote in the House of Commons, it repealed the Stamp Act. But by an overwhelming vote Parliament also passed the Declaratory Act (1766), which asserted its right to bind the American colonists by legislation “in all cases whatsoever.” In order to underline the principle at stake, albeit symbolically, Parliament retained the tax on tea while dropping it on the other enumerated commodities.

The Tea Act (1773) represented a perhaps overly clever scheme by the British ministry to score a symbolic victory against the American boycott of tea. The act retained the three-pence duty on tea owned by the East India Company, but allowed the company to bypass the middlemen in England and sell it at a discount rate in the American colonies. The point was to lure the tea-addicted colonists into paying the duty and thereby succumb to the dictates of Parliament.

The transparent scheme was exposed and ridiculed in all the major American newspapers. Committees of correspondence in all the port cities agreed on their strategy: all the British ships carrying tea would not be permitted to unload, and would instead be forced to return to England with all the tea aboard. This arrangement worked in New York and Philadelphia, but in Boston the governor, Thomas Hutchinson, would not allow the tea-laden ships to leave port. By early December 1773 matters had reached a standoff as three ships laden with 342 chests of the finest Bohea tea rested in sight of two British frigates charged with blocking their departure.

On December 16 more than seven thousand Bostonians gathered in Old South Church to debate their options. After listening for several hours, Samuel Adams, looking for all the world like a Boston dock worker but sounding like a Puritan minister channeling God’s word, rose from the chair and pronounced the discussion at an end. “This meeting,” he said, “can do nothing more to save the country.” It soon became clear that these words were a coded message to implement a plan decided on weeks earlier if all else failed.

A group of forty men unconvincingly disguised as Mohawk Indians gathered at the doorway. As they marched toward Griffin’s Wharf, they were joined by forty more men with painted faces and hatchets, moving in a column of twos like the trained militia they mostly were. In less than three hours all the chests of tea on the Dartmouth, the Beaver, and the Eleanor had been split open and unceremoniously tossed into Boston Harbor. According to strict orders, no other property on board the ships was harmed or stolen. Even the broken locks on the cabin doors were all replaced.

The next day Samuel Adams let it be known that what had just transpired was not a mob action. “These people,” he observed, as if reading from a decidedly American version of scripture, “have acted upon a pure and upright principle.” From the British perspective, of course. that principle was pure treason.

Given the winter waves and ocean currents, it took five weeks for the news of the Tea Party to cross the Atlantic. The response of the British ministry also came in waves: first shock, then outrage, then catharsis. Writing from London as a colonial agent for Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin warned that the third wave had the look of a tsunami: “The violent destruction of the tea seems to have united all parties.” It was as if a parent, confronted with a delinquent teenager, suddenly realized that earlier efforts at leniency (i.e., repeal of the Stamp Act) were misguided. The time had now come to end all presences of parental patience and show the imperial face of the British Empire.”

George III set the new tone in his message to Parliament. What he described as “the violent and outrageous proceedings of the Town and Port of Boston” had crossed a line and done so defiantly. It was now incumbent on both houses of Parliament “to put an immediate stop to the present disorders [by imposing] permanent provisions for securing the execution of the Laws, and just dependence of the Colonies upon the Crown and Parliament of Great Britain. The American colonists had created this crisis by their brazen display of disrespect for Parliament’s authority, which now must be reasserted in no uncertain terms. “The die is now cast,” the king wrote to Lord North, “and the colonies must either submit or triumph.”

See “Boston Harbor a Tea-pot This Night!”

by Benjamin Carp in the Spring 2024 issue

Submission means subordination and, if it proved necessary, subjugation by military force. If it should come to that, the king’s military aide, General Thomas Clarke, assured him that the outcome was preordained. With a mere regiment of grenadiers, Clarke boasted, he could “march the length of the American continent and, along the way, geld all the Males, partly by force and partly by a little coaxing.” If you were deciding to cross the Rubicon, it was comforting to know that the victorious outcome of all battles on the other side was already assured.

During the spring of 1774, Parliament set the course that would define Great Britain’s imperial agenda for the next seven years, culminating with the surrender of General Cornwallis’s army at Yorktown in 1781. Knowing as we do that a catastrophe was in the making, what leaps out is the utter certainty of Great Britain’s governing class as to what direction they were taking the empire. What was at stake was nothing less than the ultimate and absolute sovereignty of Parliament as the epicenter of power within that empire. And it was equally dear that the epicenter of resistance to that sovereignty resided in New England, more narrowly in Massachusetts, most visibly in Boston.

The name given to the legislation passed by overwhelming majorities in both houses of Parliament in spring of 1774 was utterly accurate. Called the Coercive Acts in England, somewhat later the Intolerable Acts in America, the legislation was explicitly designed to coerce the residents of Boston in ways that felt intolerable, and thereby send a signal to all their co-conspirators in New England and beyond that the same fate awaited them if they proved equally defiant.

The Boston Port Act closed the harbor to all exports as of June 1, effectively ending all commerce on which the economy of Massachusetts depended. Only provisions for the occupying British army and a few essentials like firewood could be imported. Enforcement of the boycott rested in the capable hands of the British navy. All these devastating restrictions would be lifted only when the king was satisfied that the perpetrators of the so-called Tea Party were properly punished and full restitution provided to the East India Company for the destroyed tea.

The Massachusetts Government Act significantly revised the Massachusetts Charter of 1691, enlarging the authority of the royally appointed governor at the expense of the popularly elected branches of government. The Council or upper house would be appointed by the governor rather than chosen by the legislature. All judges and sheriffs also became royal appointees. Finally, all town meetings, which were generally regarded as the engines of discontent in the colony, were confined to one meeting a year and prohibited from discussing issues beyond their local orbits.

In order to implement the new political structure, General Thomas Gage was chosen to serve as governor-general, thereby imposing martial law for the foreseeable future. ln the commission appointing Gage, the colonial secretary, the Earl of Dartmouth, saw fit to mention that his new assignment would quite likely demand the display of military power, since “the sovereignty of Parliament over the Colonies requires a full and absolute submission.” Although he was the senior British military officer in America, Gage was married to a prominent American woman who was rumored to harbor sympathy for the Cause, and he himself carried doubts about the Coercive Acts and the aggressive direction of British policy.

The Administration of Justice Act revised the court system so as to remove control from local juries in all cases involving customs officials or British soldiers accused of a crime. Trials of such offenders were transferred beyond the borders of Massachusetts to Halifax, Nova Scotia, or, if necessary, all the way to London.

There is a strange discrepancy between the huge majorities that supported passage of the Coercive Aces and the record of the debates in Parliament, which make it appear that a robust opposition was present to contest the eventual outcome. Most likely, the majority of members realized from the start that their voices were unnecessary because the conclusion was foreordained.

Prime Minister Lord North, whom Horace Walpole described as having a face that “gave him the air of a blind trumpeter,” felt disposed to permit opponents the full range of their eloquence, since such generosity won him the respect of his peers while costing him nothing. As a result, anyone reading the historical record must guard against concluding that there was a sizable faction in Parliament that recognized the ominous path down which their colleagues were taking the British Empire. “You are not contending for a point of honor, gentlemen,” pronounced Alexander Dowdeswell, “you are struggling to maintain a ridiculous superiority.”

In another dissenting voice, Colonel Isaac Barre, argued that, “Parliament may fancy that they have rights in theory, but these rights can never be put into practice short of war.” General Henry Conway predicted, “These acts, respecting America, will involve this country and its Ministers in misfortunes, and I wish I need not add, in ruin.”

Most eloquently, and certainly at greatest length, there was Edmund Burke, a one-man Irish army on his feet, who, despite his youth, had already earned a reputation as the most impressive speaker in the House of Commons. Burke compared the Boston Port Act to “an order delivered to the British navy to bombard and destroy the town and people of Boston. This is the day, then, when you decide to go to war with all America.”

Finally, most poignantly, there was William Pitt, still regarded as the most distinguished statesman in Britain for the brilliance of his leadership as prime minister during the Seven Years War. Recently elevated to the peerage as Earl of Chatham, Pitt was beloved in the American colonies as the Great Commoner for his impassioned opposition to the Stamp Act and his famous pronouncement, “l rejoice that America has resisted.” (His pro-American legacy is enshrined forever in the major American city that bears his name.)

If Pitt had been slightly younger, less ill – several of his biographers think he was bipolar – or perhaps a less singularly independent figure, there is no question that he could have commanded the field of British politics in 1774. It is therefore, in retrospect, almost impossible not to imagine Pitt as prime minister in lieu of the wholly managerial, willfully vague, comfortably inadequate Lord North.

But it was not meant to be. Pitt himself let it be known that he was no longer up to the challenge. He appeared in the House of Lords only once during the debates over the Coercive Acts. “My Lords, I am an old man,” he explained to those accustomed to looking toward him for leadership. He did muster the energy to urge his colleagues “to adopt a more gentle mode of governing the Americans.” His reasoning echoed Franklin’s vision: “For the day is not far distant,” he predicted, “when America will vie with these Kingdoms not only in arms, but in arts also.”

Instead of worrying about America’s growing strength, he encouraged all liberty-loving Britons to welcome it. As for the sovereignty question, he described the current obsession with enforcing that principle at the expense of the Bostonians as a sign of weakness rather than strength. (One British historian has called Pitt’s recommended policy the doctrine of “sleeping sovereignty.”)

Based on the votes on the Coercive Acts, fewer than one in ten of his fellow Lords were prepared either to listen or comprehend what he was saying.

Benjamin Franklin, who was the most prominent American in England at the time, wrote an essay in 1773 mischievously entitled Rules by Which a Great Empire May Be Reduced to a Small One. His clear intention in Rules was to force the British government to view the current imperial crisis through the eyes of the colonists, and to frame his argument in a satirical format that rendered it impossible to rebut without appearing ridiculous. “I have held up a Looking-Glass in which some Ministers may see their ugly Faces,” he explained, “and the Nation its injustice.”

Here are three of his mock recommendations to the members of Parliament:

Franklin’s satirical essay appeared in several British publications to mixed reviews before it traveled across the Atlantic, where it met with nearly universal acclaim. In terms of Franklin’s political career, the publication of Rules marked the moment when he stopped serving as an evenhanded arbiter between the two sides of the Anglo-American argument.

A few months later, in January 1774, he was forced to stand in silence before an assemblage of Britain’s most prominent officials while being demonized as the embodiment of American insolence and ingratitude. By then the gap between the British and American camps had widened into a chasm that could no longer be straddled easily. It was now clear for all to see that Franklin stood squarely on the American side. The British had just lost the American Prometheus.

The passage of the Coercive Acts in the spring of 1774 represented Parliament’s willful decision to transform Franklin’s clever satire into a bad joke. It was almost as if Lord North’s followers in Parliament took their cues from Franklin’s essay. His catalog of British blunders became the political framework for their nonnegotiable imperial agenda. Looking back to this moment a year later, Edmund Burke delivered the epitaph for the Anglo-American vision that he, Pitt, and Franklin had tried so hard to defend, in words that Franklin could easily have spoken: ‘‘A great empire and little minds go ill together.”

The American response to the Coercive Acts was instantaneous and predictable. “For flagrant injustice and barbarity,” Samuel Adams proclaimed, “one might search in vain among the archives of Constantinople to find a match for it.” Down in Philadelphia, John Dickinson observed that “the insanity of Parliament has operated like inspiration in America. The Colonists now know what is designed against them.”

The new rallying cry, which began to appear in pamphlets and newspaper editorials up and down the Atlantic coast was “Common Cause,” which described a shared sense of solidarity uniting all the colonies in support of their besieged Boston brethren. The transparent strategy of the British ministry to isolate Massachusetts had backfired, producing exactly the opposite outcome.

The Americans, it turned out, were also prepared to cross the Rubicon, but in the opposite direction.